In The Distribution of the Sensible, Rancière claims that “politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time” (Rancière 2004, 13). It is through a metaphor of visibility, what is “seen”, that he defines the realm of the political. In Notes towards a Performative Theory of Assembly, Butler considers and extends Arendt’s idea of the space/field of appearance as the political realm where humans recognize one another as such and take action. She significantly emphasizes the fact that not all human subjects are equally recognizable and, hence, the differential conditions of appearance which govern the political. For both theorists, the space of appearance or the realm of the political is exclusive (for Ranciére because of the particular demands on the working class and for Butler given the historical systems of colonial and patriarchal power that govern it) but their aspirations are ultimately oriented towards their expansion not their dissolution.

The benefits of visibility, of recognition, of representation can easily be taken for granted. Social justice discourses regularly deploy these terms as a way to expand the “protection” of the State (i.e. the legal system) or to alter the political sphere through the introduction of new actors. Many of the established discourses and conventional practices of resistance within neoliberal democracies today rely on the visible intervention onto “public space”. While theorists consider the significance of a space of appearance and recognition, activists consistently rely on protests, occupations, strikes, boycotts, or other interventions on public space to act and intervene on unjust social/legal formations. The current dynamics surrounding migration, particularly the precarious conditions faced by undocumented immigrants in the US, however, might force us towards alternative theorizations of the visible and its politics.

The legal charging document that initiates the removal proceedings against undocumented immigrants in the United States is called a “Notice to Appear” (NTA). The document specifies one of three reasons for the initiation of deportation proceedings: being an “arriving alien” stopped at a port of entry, an immigrant already in the US who has not been formally admitted or an immigrant who was formally admitted but is now deemed deportable. Receiving an NTA means that one must appear at Immigration Court on the date specified, it represents the enactment of “due process” where migrants have the right to have their cases heard before a decision is made. This appearance, or making visible, of the undocumented migrant before the legal system might be considered an instance of recognition (or misrecognition) within the public sphere. It can be considered in terms of potential for action or an otherwise political encounter, but would those migrants not be better served by a claim to the right not to appear? While being undocumented clearly represents a precarious existence, isn’t it so partly because of the persistent threat of exposure, the threat of being forced to “appear”?

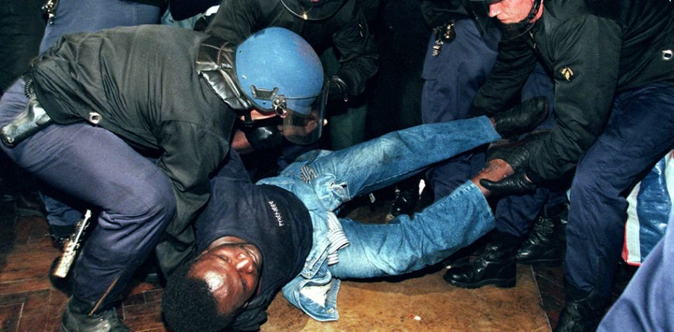

In March 1997, Balibar delivered a speech in solidarity with the Sans-Papiers of Saint-Bernard, a group of around 300 African migrants who in June 1996 occupied the Saint-Bernard Church in Paris to demand legal residency. He begins by saying that the French are “greatly indebted to the ‘sans-papiers’ who, refusing the ‘clandestineness’ ascribed to them, have forcefully posed the question of the right to stay”. Through the organization of the movement and their appearance within the political sphere, the sans-papiers were able to make the claim to the right to legal residency as well as the right to have rights. Balibar further emphasizes that this is revealing of the nature of democracy as “an institution of collective debate, whose conditions are never imposed from above” where “people must always conquer the right to speak, their visibility and credibility, running the risk of repression.” The risk of repression, however, proved to be a significant one given the turn of events for the sans-papier movement and the occupation of the church. Towards the end of August 1996, the French police brutally evicted the sans-papiers from the church. Many of them were subsequently deported from France.

What, then, does visibility actually do?

These examples do not seek to discount the political potential of resistance based on visibility. They do, however, raise questions about the necessity for alternative conceptualizations of resistance through “clandestineness”, deliberate invisibility or a rejection of appearance. Considering the contemporary conditions of state (and corporate) surveillance, as well as the history of policing which defines their logic, how can we consider the limits of visibility as emancipatory? How can visibility itself produce precarity? Can performances of resistance be fragmented? Can they resist their own impulse to monopolize the gaze?

While I question Balibar’s premise of an absolute democratic benefit to visibility (Were the sans-papiers not already forced into a kind of new legal visibility by the enactment of Pasqua laws in 1993?), his speech further gives us a foundation for alternatively conceptualizing resistance. From these events, Balibar theorizes the concept of citizenship, not as an institution or as a status, but rather as “collective practice”. This concept is also briefly pointed to in his essay Three Concepts of Politics in an account of the concept of equal liberty:

[Rights] cannot be granted, they have to be won, and they can only be won collectively. It is of their essence to be rights individuals confer upon each other, guarantee to one another…There is autonomy of politics only to the extent that subjects are the source of ultimate reference of emancipation for each other. (Balibar 2002, 4)

I am interested particularly in the latter part of this claim – the recognition of rights between individuals. Subjects as the reference of emancipation for each other. Rather than performing resistance through action in public space, through protests or strikes which reinforce the State as the entity capable of granting or recognizing rights, how can we resist differential governance by protecting, shielding or hiding our neighbours from the threat of visibility, of a necessarily exclusive (legal) public sphere? How do we reimagine solidarity so that precarity is not further reproduced and intensified towards those most vulnerable? What tactics of resistance should we adopt to face a State which demands formal appearance and visibility?

Key terms: Migration, Law, (In)visibility

Example of political spectacle: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bJ8gHreLdgg

Works Cited

Balibar, Etienne. 1996. “What we owe to the Sans-papiers” European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies. http://eipcp.net/transversal/0313/balibar/en.html

Balibar, Etienne. 2002. “Three Concepts of Politics: Emancipation, Transformation, Civility” In Politics and the Other Scene, 1-39. London: Verso Books.

Butler, Judith. 2018. Notes Towards a Performative Theory of Assembly. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. New York: Continuum.