The morning after Donald Trump got elected as the new POTUS, my close friend and roommate Juan Manuel told me: “Por primera vez los gringos entenderán lo que es tener un payaso ridículo al mando.” Juan Manuel, a Venezuelan exile, was right. As a Venezuelan and a Mexican we were used to extremely cartoonish political figures. Presidents of the United States, no matter how evil, racist, or ridiculous they were, always had a ring of protection which manifested itself as experts in political PR and communications. In a strange manipulation of his own image, Trump appears to shed that ring of protection for his own handling of his presentation, which is mostly distributed via television and social media. This week’s readings highlight the way new media shapes our social and cultural political landscape. From Trump’s tweets to his theatrical expressions, to online social mobilizations, to the reconceptualization of citizenship via selfies into what Poster defines as netizenship.

In many ways I was moved by Taylor’s text, given that my own politics of passion are deeply entangled with the subject matter. As a fourteen-year old at the time of AMLO’s mobilization, I mostly observed the “animatives” that were activated in the city as an external actor. Animatives are described by taylor as “part movement as in animation, part identity, being, or soul as in anima or life. The term captures the fundamental movement that is life (breathe life into) or that animates embodied practice. Its affective dimensions include being lively, engaged, and ‘moved.’” (Taylor) For me, it wasn’t until the following election in 2012 (my first time ever voting), that those animatives interpolated my own body. Seeing how the media had protected and enhanced the image of then political candidate Enrique Peña Nieto, which included the attempt to de-legitimize a student protest against him which happened in Universidad Iberoamericana. The protest had happened when EPN visited the private university to give a conference. Students protested his presence and questioned him on the murders and rapes that happened in Atenco, a massacre he authored in 2006. Frightened EPN hid in the bathroom. The following day the media claimed the protestors were not students but pawns from other parties. Thus, the students who were present began circulating a video in which each one of them presented their student ID on camera. Asserting their presence and their actions against the candidate of the PRI party. One hundred and thirty one students showed up in the video, unleashing the student movement #YoSoy132. Echoing previous movements we marched amongst many routes from Tlatelolco to el Zócalo.

Edward’s understanding of “The selfie determination of nations” (Edwards, 28) resonates in a very particular way with how this movement started. As it began with an assertion of singularity within a collective practice, and it happened via each of the students action of self-taping and sharing of another form of individual identification which was their student ID. As borders, media, technology, neo-liberal economies shift so does the concept of the citizen. Consumption thus has transformed into a form that quantifies and qualifies our relation to the state and to the body politic. Particularly helpful perhaps is Poster’s invitation to call into question the term citizen in and of itself, as well as the way this term has come to denote a “sign of the democratizing subject”: “Does the term citizen carry with it a baggage of connotations from Western history that render it parochial in the globalized present? (Poster, 76).

These readings invite us to disrupt, question, and imagine, even if there ́s an impending threat of failure. For “even in failure, if we measure failure by the absence of a plan for a future society, insurgencies will have had a measure of success (Arditi)” We must find, in this disruption the potential where new digital economies can open up new political landscapes. Potential is not in the way they subscribe to a specific future but in their demand for a change, a transition, in the way the present demands the potential of a future, even if that future is not specifically outlined.

Category Archives: Week 9

Fact-Checking a Fiction

CBC News: The National

U.S. President Donald Trump remains popular among supporters despite the possibility he could be the first president to seek re-election with impeachment on his resume.

The readings and video this week definitely struck a chord with the importance of narrative in political spectacle and even in the ascension of the political sphere. Machiavelli’s analysis The Prince, on how one is to ascend to power and subsequently keep power, resonates strongly today in our political arena, and illuminates just how long these questions have been circulating in society. For instance, Chapter XVII in the book, “Concerning Cruelty and Clemency, and whether it is better to be Loved than Feared,” has been a resounding refrain throughout dramatic depictions of political arenas (and throughout historical arenas, though I personal was not in the room for those discussions.) In television shows such as “Game of Thrones,” “House of Cards,” and so many others (better than these two), I am confronted with the themes, the questions of: “Is it better to rule out of love or fear?”, “Do I want to be respected or feared?” Is there a difference?

The importance of narrative is inextricably linked to all of the points in Machiavelli’s analysis. The power of narrative can lead folks to their slaughter, as is demonstrated in Chapter VIII on “wickedness,” serve as a tool for mitigation, and if powerful enough, we are faced with the reality that it is often powerful than fact, especially today. Richard Schechner defines Make Belief as, “when these kind of [make-believe] actions create a substratum of belief, reinforce a substratum of belief even as they create it, that people are willing to die for.”

Let’s take Trump. Trump is someone I believe people, his supporters and opposers alike, would die for if given the opportunity. The article “Trumpism Extols Its Folk Hero,” Charles Blow states, “I believe that, like Edwards, Trump ascended to folk hero status among the people who like him, and so his lying, corruption, sexism and grift not only do no damage, they add to his legend….The folk hero, whether real or imaginary, often fights the establishment, often in devious, destructive and even deadly ways, and those outside that establishment cheer as the folk hero brings the beast to its knees.” Trump as ascended to this folk hero status by spinning his narrative in the way that makes him nearly immune to “fact-checking” or any sort of logical opposition. Blow ends the article by asking, “How does one fight fiction, a fantasy?” How do you fact-check a fantasy?

Elizabeth Kolbert’s New Yorker article, “Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds,” is a smart investigation into the “collective consciousness,” and examines scientific studies which prove that we – as a society, as a collective – don’t think alone. We do not understand how everything works in this world, and usually that is acceptable, except when it comes to making political decisions. Her reference to the Gormans was most interesting with, “The Gormans, too, argue that ways of thinking that now seem self-destructive must at some point have been adaptive. And they, too, dedicate many pages to confirmation bias, which, they claim, has a physiological component. They cite research suggesting that people experience genuine pleasure—a rush of dopamine—when processing information that supports their beliefs. “It feels good to ‘stick to our guns’ even if we are wrong,” they observe.” Politics are so hairy, so exhausting, so toxic and depressing, that using a scientific entry point to examine this phenomenon is quite helpful.

I don’t believe that Trump is “making believe.” I don’t even think he believes he is lying. Trump is deep in the throes of “make belief,” and even if he is fully conscious (partially conscious, perhaps) of when he is administering false information, he is now at a place where he is occupying the space between – or above – any kind of measurable moral hierarchy; he may actually believe completely the “facts” he communicates, which in turn facilitates the “make-belief” affect in his supporters, solidifying his role as the “folk hero” for the conservative and “down-trodden,” and makes him impervious to the real facts which could, in another arena, another time, wipe him out in one stroke.

How does one fight a fiction, a fantasy?

A political

spectacle is based on making Belief through make believe (inspired by Richard

Schechner, “Make Believe and Make Belief”). There is a clear guideline given to that in The

Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli. “How a prince must act to win honour”

is the title of chapter 21, in which Machiavelli writes: “(…) a

prince must endavour to win the reputation of being a great man of outstanding

ability.” The crucially concluding question that Charles M. Blow poses

in his New York Times article Trumpism exolts its folk hero is the

following: “How does one fight a fiction, a fantasy?“. This

question overwhelms me. I cannot think of possible answers. Fiction mixed with the

important tool of the sovereign -unpredictability-, our fighting seems to become

futile. Machiavelli, p.81: “I hold strongly to this: that it is better to be impetuous than

circumspect; because fortune is a woman and if she is to be submissive it is

necessary to beat and coerce her.“ Elizabeth Kolbert, the New Yorker-

“Why Facts Don’t Change Our

Minds”, explains what became known as confirmation bias: “(…) the

tendency people have to embrace information that supports their beliefs and

reject information that contradicts them”

and includes Jack Gorman and Sara Gorman: “(…)cite research

suggesting that people experience genuine pleasure—a rush of dopamine—when

processing information that supports their beliefs.” We constantly

create fantasies. We are making ourselves believe and are made to Belief. A fantasy. How can WE fight the arrival

point of creation of fictions? (if “we can

hardly tell where our own understanding ends and others’ begins”? Sloman and Fernbach in Elizabeth Kolbert, the New Yorker-

“Why Facts Don’t Change Our

Minds”)

Give the People What They Want

What does it mean to give the people what they want? A common idiom in matters of commodified transaction between actor and audience, to give the people what they want implies what they want is not necessarily what they need…but hey, give it to them anyway! But why? What is so innate within a populace that an actor can deny the best interest of his audience, or the most democratic outcome, or the most Utopian of horizons, in order to sustain this onstage charade? Politically, giving the people what they want, implies the continuation of myth, the next page in a legend that contextualizes everything we, the people, need to aspire, to saunter through days; a present-day answer to whatever Westernized-American-Dream. We can watch this, then, as the Dream weaponized. Our readings this week expose the historical terms of conditions the populace agree on instinctively, as spect-actors do, in order for the ruling class to make belief, weaponize dreams, disarm truths, and alter realities.

“Give the People What They Want” is a pretty popular Philly Soul track from the O’Jays that spent one week at the top of the R&B Single Charts in ‘75, peaking at number 45 on the Billboard Hot 100. It was regularly used at campaign events during Barack Obama’s 2008 Presidential Campaign. Another track by the same name was written by The Kinks in 1981, as the English rock band’s response to the fascination of the abomination splattered across American TV. Here, the musician asserts the role of bard, as if delivering a message from the Otherside, a plane of existence that is not confined by earthly limitations, but is still privy to the trials and tribulations that comprise the lives of ordinary citizens.

Giving the people what they want suggests a collective sanction that Machiavelli professes is perpetually underlying; omnipresent and overarching; foundational and supportive. It is the continued legend of sovereignty latent within the realm of politics just as much as it is another indication of our abdication to Doom-Give the people what they want…because they know not what they need, nor should they, for if they did, perhaps that which they needed would not reflect our (the Rule’s) best interest.

Therefore, the bard, the shaman, the folk, is styled, ever in-draft, as performatic allegory, giving you modern tragedy, serving up Death and all his Biopolitcal Friends. In such an enshrouding fabulation, the folk hero (as in the Man, the Myth, the Legend), thrives like a Criminal, the taste of glory forever on the tip of his lips, but never in his grip. Like some obscene after hours show on repeat, this dreadful pornography is lore-making, and the constant aversion to the laws of nature or man (or both) sting like a delayed orgasm.

Which, it seems, might be at the root of giving the people what they want. What they want is to keep wanting to keep pining; an encore without applause; a show that is episodic, but free from threats of cancellation. In this way, the populace can continue relying on the perceptions of others to help sharpen their teeth, feed their egos, break their jaws. In turn, we don’t even have to blame ourselves, nor the folk hero in which we base our beliefs; we can simply blame the way things are on the way things have always been; at the feet of Legend; an abdication of Doom.

In “Why Facts Don’t Change Our Mind,” Kolbert highlights different experiments and findings revolving around the human faculty of reason and its relation to fact. In the vastness of the modern age, she argues that “incomplete understanding is empowering,” and there is a pleasurable rush of dopamine involved in the sanction of fallacy and depth that often constructs a community of knowledge. It is this capability to be social, to learn and trust in another’s performance, that has formed the basis of reason as an evolved human trait. It is with great cunning that bad actors, those audacious enough to see themselves as princes, mislead a populace into the erroneously scientific, the perceived natural, through the ritual performance of Doom, the false pulpit of royalty, and the security within Fear, that Machiavelli tells us is supported by the dread of pain, which is forever implied in this darkened theatre.

Fighting a Fiction

This week’s readings alerted me to the importance of highlighting the difference Prof. Schechner highlights between make believe and make belief to citizens. It seems that as politics have been shaped over time, the conception of power has long been shaped in between the tensions that are held in the narrow moments that separate (or join) the make believe from the make belief. Power, as Machiavelli shows us, has become a key tool of the political leader. How to obtain it, maintain it, reproduce it, and expand it is the key concern of the leader figure Machiavelli speaks to. A prince who understands that manipulation, specifically the manipulation of love and fear, is one of his greatest allies: “Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception.” This prince, has unfortunately not changed much as in 2019 we still endure leaders who have constructed a fiction of themselves. A fiction so strong that it shapes unbreakable ideals. Elizabeth Kolbert wonders how can we open the eyes of people, when the line of fact and fiction is blurred when it comes to the way belief is shaped: “Providing people with accurate information doesn’t seem to help; they simply discount it. Appealing to their emotions may work better, but doing so is obviously antithetical to the goal of promoting sound science.” It is here where art must intervene. If “appealing to the emotions” may be better, and there is no better way of understanding emotion and affect than via art, then perhaps it is now more urgent than ever that we look to art as a political tool. Otherwise, I echo Charles M. Blow in wondering: “How does one fight a fiction, a fantasy?”

The Ethics of Statesmanship?

After never quite grasping the epithet Machiavellian, reading The Prince directly with historical distance created shockwaves within me: has anything really changed since the sixteenth century Italy, are we doomed to reproducing the dynamics of power at the expense of the planet and all its inhabitants? Machiavelli offers logical arguments for the sustainable administration of principalities (as opposed to republics): “what all prudent princes ought to do, who have to regard not only present troubles, but also future ones” (27). He fancies himself a keen observer of human nature, from the highest examples of nobility to the faceless majorities that principalities encompass. While democratically-elected republics conform our current understanding of political spectacles, Machiavelli’s views on the ethics of statesmanship and the art of war can still inform our ways of interpreting the roles and actions of contemporary political actors.

While elaborating a robust ensemble of international affairs and public relations, princes are presented as actors in front of an audience, on the world’s stage, manipulating affects, bending the map to their will, the literal embodiment of the dialectics of power. Contemporary politicians and Machiavellian princes, using Schechner’s terms, are still urged to make their constituents and subjects believe their hegemonic discourses on domestic as well as international issues; with the world spiraling towards the right and fascism, we are made to acquiesce to their belief systems, to take part in their secretive negotiations by offering our bodies to their whims and ambitions.

While reading Machiavelli, certain personality traits—which we would hold as detestable in acquaintances—are ideal for the administration of state powers: facetiousness, fickleness, ruthlessness, compassion only when necessary, cruelty as a medicine liberally administered. He offers examples of “great men” who have ruled principalities in the past and critically examines their labor, their pitfalls, for signs of laudable statesmanship or insufferable weaknesses (and every shade of tyranny or liberalness in between). Also, by juxtaposing the will of the people to the will of the nobility, Machiavelli still operates within a system of politics in which a statesperson must negotiate between differing interests, between dangers from within and from without, dangers from the past, the present, and the future, by recognizing that the influence of the affluent minority is just as challenging and important to manipulate as that of the majority, though less righteous than the latter.

Then I ask: how can Machiavelli sermon about righteousness, when he is talking about the ethics of power, if his Machiavellian princes can be called ethical at all? When inconstancy and opportunism are political ideals, how can there be morals, how can there be a constant ethical framework upon whose foundation a people and a principality can achieve democratic freedom like we aspire to have in our contemporaneity? When power is its own dialectic, its own desire of itself, ad infinitum, where can the limit of morals be placed?

If anything we can learn from Machiavelli, is that his text needs to be read with historical distance, with utmost care, and more consciousness than those political actors today that see in the Machiavelli prince “a great man”, a model to uphold. Spectators caught in the maelstrom of political spectacles should heed Kolbert’s warning of being trapped into believing what we want to believe, to feel truths subjectively and not observe them factually, when we know, through Machiavelli and elsewhere, that contemporary politicians (not unlike Machiavellian princes) are always making belief, moving chips not in our favor but in the stead of maintaining power, first and foremost.

The Prince

Machiavelli’s The Prince develops an account of the way power is acquired and retained. Through a careful examination of distinct historical cases, the book presents key tactics for leaders to manage populations and keep control. In particular, Machiavelli focuses on Principalities, sovereign states run by monarchs, as opposed to Republics. Even though this form of government is now relatively rare, it is almost impossible not to think of the contemporary cases that continue to reflect these dynamics today.

In Chapter 3, titled “On Mixed Princedoms”, Machiavelli discusses the significant difference between the conquest by States “of the same Province and tongue as the people of these dominions” and the conquering of areas by more foreign States. He argues that it is easy to retain dominion over populations that share the same language and customs, while it is much more difficult to dominate culturally distinct populations. The continuity in the cultural life of those conquered means that people may “live peaceably with one another” still. This recognition of the need for cultural considerations in governance might help us understand the rise of anti-immigrant discourses within Western democratic states and the right-wing anxiety that surrounds migration discourse. The threat to the dominance of particular cultural practices is given significant political force.

I was also struck by the significance that Machiavelli assigns to affect in monarchic governance. He discusses the “love” that subjects must feel for their ruler – a love that should not be distributed among a multitude of nobles but that should instead be concentrated in the singular figure of the Prince. “Hate” is also theorized as a powerful force that threatens the rule of a monarch. I wonder how these emotions are reorganized in a democratic model – do modern institutions and procedures for governance redistribute (or diffuse) affect? How can these observations be applied to contemporary cases of populism?

Digital Prince

Machiavelli’s “Prince” was published in 1532 almost 500 years later Edwards analyzes Trump’s performance as president in a similar manner with a bit of technology. In this short essay, I am not only going to look at the power construction of these two images of a leader (that has been studied extensively), not also the notion of analog and digital when it comes to Trump as a politician.

The massive use of digital space, the adaptation of TV show methodology to politics and constant comparison of Trump to the idea of a president (which is somewhat vague) makes him a great candidate for a classical concept of digital that Critical Art Ensemble brings up. The digital model in an assembly line is a copy of a unique analog that came out of chaos or no specific order before itself, while the digital comes from a known order like contemporary politicians have regulations written before them that they have to follow. However, the digital copy still must “stand the test of equivalence” to the analog, and Trump had to persuade that he is a valid digital president.

Machiavelli said that “the actions of a new prince are watched much more than those of an hereditary one, and when they are recognized as virtuous, they attract men much more and bind them much more to him than ancient blood would do.” In terms of Trump, being a new prince means not being a politician before the election and having every movement and word watched, or being a digital version of a president. According to Edwards, the celebration of Ryan Owens heroic death was considered as the “virtuous” action when “he became President of the United States in that moment” because “Trump brought the logics of the entertainment realm in which he had achieved global recognition” to the space of politics. Thus, “Trump achieved the blurring of the distinction between American popular culture and US foreign policy.”

Edwards underlines that Trump adapted the methods of reality TV shows and shifted the medium in the Capitol chamber from Hollywood cinema of Ronald Reagan to reality television. In this instance, Trump brought to politics methods from dominant culture of his time and “theatre of everyday life” that is the process of copying in digital aesthetics – “a process that offers dominant culture minimal material for recuperation by recycling the same images, actions, and sounds into radical discourse.” The constant repetition of Trump’s methods is a technique of arranging what people can see and, thus, believe. “The people are fickle; it is easy to persuade them about something, but difficult to keep them persuaded.”

The digital expansion of Trump’s politics develops the force in Machiavellian terms as it is not about physical but informational dominance, especially through the internet. Poster thinks that “the internet holds the prospect of introducing postnational political forms because of its internal architecture that is not centered and cannot be controlled.” However, the case of new politics with digital leaders as Trump shows that the internet still operated under the power structures.

How to shape a fact?

The Prince by Machiavelli may be presented to the monarchy`s education at that time. As a 21st century female, for me, the book seems more presented the ordinary people—the tools of ruling never changed dramatically in the course of history. The ruling class is always good at shaping a fact by appearance, even without the book. As Machiavelli said: “Everyone sees what you appear to be, few experience what you really are.” Ordinary people`s thought seems so easy to be controlled, if they never learned how to be a critical thinker: “The vulgar crowd always is taken by appearances, and the world consists chiefly of the vulgar”.

To be more clear, politics maybe never about truth. It is a performance. As Richard Schechner said in the video of “Performance Studies: An Introduction – Make Belive/Make Belief”–Performance creates belief, create reality. Politician is always making belief by rehearsing, preparing and reiteration.

To be more specific, Kolbert uses several studies of experiments to demonstrate the performance of politicians and Journalism why facts couldn`t change our minds. “Once formed, impressions are remarkably perseverant”. Kolbert pointed out that the phenomena is originated due to human`s evolution system. People naturally inclined to embrace the information that seems to support their thought: “Consider what’s become known as ‘confirmation bias,’ the tendency people have to embrace information that supports their beliefs and reject information that contradicts them”. Furthermore, Blow discussed his mother`s example to show how people involve folk hero`s fantasy. Here, shaping fact is not only about information, but about the whole imagery of politicians.

It is fresh that people tend to have much more moral tolerance to folk hero. They created heroes by their imagination, to make the people own the performativity. Blow thinks Trump is using people “folk hero fantasy” to relish his criminal and corruption. He created the imagery by his preservation. Blow sharply pointed out: “I think it is a mistake to believe that Trump’s supporters don’t see his lying or corruption. They do. But, to them, it is all part of the show and the lore. They have personal relationships and work relationships like the rest of us, and those relationships depend on honesty and virtue. They, like my mother did, are allowing in him something that they would not allow in themselves”.

Make Belief Masks

This week’s readings focus on the creation of a political leader. Beginning with The Prince, Machiavelli lays out a blueprint for taking and maintaining power in political regimes. He notes hereditary states and mixed monarchies can be conquered by killing the old monarchies. He further argues, it is necessary to be violent towards self-governed republics because, “it will destroy you, if you don’t destroy it” (p. 19-20). A prince may rise to power by following the examples of previous rulers and by creating a spectacle of power. To win respect, a prince must create the image that he is both a “genuine friend and a genuine enemy” (p. 88). I believe this can be seen in Schechner’s concepts of make believe and make belief. Schechner explains, make believe involves a conscious application of the mask or con game; make belief is when that mask reinforces a strongly held belief that people are willing to act in support of (such as a religious or political belief). Where make believe and make belief overlap is in politics, wherein the politician wears their script as a mask, but asks the spectator to accept the mask as truth.

Kolbert (2017) explains, impressions of truth that fall in line with people’s beliefs are incredibly resistant; even after those impressions have been revealed as false or untrustworthy. They explain, confirmation bias is one entry point to understand why people have a hard time changing their minds/beliefs. Kolbert (2017) finds we hold onto beliefs (even when we could be wrong) because we don’t want to be betrayed by others or simply put, we don’t want to get screwed by those who believe differently than we do. It is for this reason that we must beware the folk hero who often fights the establishment in the name of the people (Blow, 2019). As spectators, we must be critical of those who have used the transcendence of make believe and make belief as a mask for their political advantage.

more than pervasive

The digital is no longer a pervasive part of our reality; no longer a frightening specter looming behind screens, trapped. Indeed, it is our reality; or, as Mark Hansen argues in his book Bodies in Code, our reality is now best thought of as “mixed reality.” As with mixtures of other types, the ingredients—the digital and the “real”—lose what clear separation or distinction they appeared to have before: they are blended to make something new.

Analyses of our mixed reality often find the most fertile soil for investigation in social media. Along these lines, social media, such as Twitter and Instagram, are most fruitfully approached not as isolatable or individuated bodies, but as networks in which a vast array of lifeforms and systems are deeply entangled: not just ‘the human’ and ‘the digital’ but a multiplicity of communities, ecosystems, belief systems, and so on and so forth. An analysis that exemplifies such an approach is found in Brian T. Edwards’ essay “Trump from Reality TV to Twitter, or the Selfie-Determination of Nations.” Here, Edwards demonstrates the entanglement between newly emerging technologies and the emergence of new social forms. Edwards shows us the mechanics of the movement of Trump’s boardroom from his reality TV show The Apprentice to the cabinet room and how this movement was facilitated through his social media campaign: “the simulacrum board room of The Apprentice anticipates the transformation of the White House Cabinet Room at the televised live sessions in the early months of 2018.” Social media were the means through which Trump’s campaign propagated the image of himself as a successful business tycoon, allowing him not only to move out of financial distress but to constitute a public for himself, providing analyses such as Edwards’ with a demonstration of the image economies and ‘common sense’ formations articulated by Ariella Azoulay and Jacques Ranciére.

As we begin to understand the mechanics—the logics of circulation, as Edwards would call it—of our mixed realities, we also begin to understand the instability of the concept of ‘citizen’ which we have long taken as political bedrock. Mark Poster, in the chapter titled “Citizens, Digital Media, and Globalization” from his book Information Please: Culture and Politics in the Age of Digital Machines problematizes the term ‘citizen’ in four ways: first, the principles of the term derive from the West, and the West is responsible for an imperialist and capitalist form of globalization; second, the principles (of natural rights), rooted in the Enlightenment, require one to extract oneself from the social in order to proclaim the universal as natural; third, the conditions of globalization are not only capitalism and imperialism, but also the coupling of human and machine, and we therefore may build new political structures outside of the nation-state only in collaboration with machines; fourth, linked with machines in a global network, the citizen has become something else. Poster proposes instead that we speak of netizens: the citizen of mixed reality.

This movement from citizen to netizen would certainly constitute the type of movement towards digital logics called for by the Critical Arts Ensemble (CAE). In their essay “Recombinant Theatre and Digital Resistance,” this type of movement is described as a surrendering of the values and certainties of analogic cosmology. Digital logics, according to the CAE, are those that offer an ongoing flow of sameness: order from order. Alongside analog logics, the CAE speaks of ‘hybridization’ in the Western style of marketing. This hybridization is an articulation of mixed reality applied specifically to marketing strategies, which, as we’ve seen, are invested not only in what we’ve traditionally thought of as ‘products’ of consumption, but also in people—in Presidents. Thus, the concept of hybridization is of crucial importance to our current understandings of political spectacle, and the CAE defines it by explain that “on the one hand, the consumer wants the assurance of reliability provided by digital replication, and on the other hand, desires to own a unique constellation of characteristics to signify he/r individuality.” I want to conclude with a couple questions with regard to what this concept of hybridization may imply about current social logics and organization in light of these essays, and to offer a possible problematic at work here in order to see where we might build on these analyses.

In our mixed realities, these hybridized Western marketing strategies are seemingly ubiquitous. I am interested in the implications of the definition of the ‘digital logics’ at work here—that is, the assurance of reliability provided by digital replication. Recalling George H. Bush’s invocation of Clint Eastwood’s “Make my day” line in his 1988 presidential debate with Michael Dukakis (examined in Edwards’ essay), we ask how this invocation carried with it a summoning of racist logics of Eastwood’s film. This “make my day” line can be seen as one such “assurance of reliability provided by digital replication,” as it signifies a carrying over of racist logics without needing to explicitly lay them out. Digital logics, then, cannot just be thought of as being confined to digital coding of 0’s and 1’s, but is also coded into the languages we are speaking in our conversations every day. Therefore, coding is not only about digital replication—a form of replication that is treated in these essays as recently emergent—but the replication of logics that have been in operation for centuries. Can we, then, approach ‘coding’ as a means of anticipating social organizations and ‘mobilizations’ of affects in marketing (/presidential) campaigns? If so, then I think it is important to problematize the ‘netizen’ invested in these campaigns. The netizen, though it offers a means of understanding mixed reality, forgets the social foundation of the Internet (which, I believe, is also the social foundation of mixed reality more generally): it is about networks, not individuals. The netizen thus seems to carry with it the Enlightenment illusion of individuality—that compulsion to “extract oneself from the social order to proclaim the universal as natural.” I think that this concept may reinscribe this Enlightenment (i.e., Western) tradition that has given ‘individuality’ and ‘body’ to persons so selectively throughout our history if we are not careful to avoid such pitfalls. Thus, we ask: Where might explorations of hybridization and mixed reality lead us if we let go of this individual?

Make America Great Again

(Observación: Las citas de El príncipe fueron tomadas de una edición en español)

Ante la pregunta sobre cómo un príncipe que conquista un Estado puede mantener su legitimidad, Maquiavelo en su obra El príncipe nos dice que cuando existe una tradición asentada, no existiría ninguna dificultad para sostener dicha legitimidad: “Me parece que es más fácil conservar un Estado hereditario, acostumbrado a una dinastía, que uno nuevo, ya que basta con no alterar el orden establecido por los príncipes anteriores y contemporizar después con los cambios que puedan producirse” (5). Así, lo difícil entonces sería sostener la legitimidad sobre un Estado cuando se produce un cambio de régimen.

En ese sentido, si pensamos que la legitimidad y el poder que tiene un Estado sobre una sociedad se asienta en la tradición, me hace pensar en la relación que tiene esto con el artículo Why facts don’t change our mind, de Elizabeth Kolbert. Si uno se pregunta, ¿por qué ganó la presidencia de Estados Unidos un hombre como Donald Trump? Resulta inevitable pensar en esta idea de tradición y continuidad que representa un hombre como él. Desde el slogan de su campaña ‘Make America Great Again” hay una resonancia con lo que presenta Maquiavelo en su texto: asentarse en el poder a partir de una tradición que permite una legitimidad más fácil, que aparenta una continuidad entre sus espectadores.

En el artículo de Kolbert, existen las mismas preguntas de por qué, conociendo los ‘hechos’, las personas no cambian de opinión: “The tendency people have to embrace information that suppports their beleifs and reject information that contradicts them”. Así, las personas, creyendo que saben más de lo que realmente saben, justifican políticas o conductas que, en relación a lo que hablábamos la semana pasada, se salen de lo que se consideraría como parte del sentido común.

Sin embargo, existe una audiencia que sigue apoyando a un sujeto como Donald Trump, el que en su imaginario, representa la continuación de una tradición, de algo que se había perdido o que estaba a punto de perderse. Lo mismo reconoce en su artículo de opinión Charles M. Blow: “I think it is a mistake to believe that Trump’s supporters don’t see his lying or corruption. They do. But, to them, it is all part of the show and the lore.”. No podemos pensar que los seguidores de este ‘príncipe/folk’ no se dan cuenta de lo que pasa, en efecto lo saben, pero una cosa es efectivamente saberlo y otra es querer, uno: aceptarlo, dos: querer que suceda un cambio. Aunque desde la oposición se intente demostrar lo contrario: “Providing people with accurate information doesn’t seem to help; they simply discount it” (Kolbert), en lo concreto, parece un tarea prácticamente inútil.

Politics of The Mind & Manipulation

Macchiavelli’s The Prince is a handbook on how to conquer and rule a land. Macchiavelli prescribes chapters on how to be in power and stay in power through tools of force and persuasion. How does one lead and persuade people to fear and to follow?

“Providing people with accurate information doesn’t seem to help; they simply discount it. Appealing to their emotions may work better, but doing so is obviously antithetical to the goal of promoting sound science” (Kolbert). This NY Times article uses information from a science experiment to explain why people can’t think straight. Even after giving people proven facts, it is hard to persuade them to change their mind or convince them of the absolute truth. This relates to tools of persuasion, or furthermore, and explanation of why people think the way they do or continue to have their beliefs even after shows evidence. So doing so, in current politics, we play towards people’s emotions more rather than the truth.

Performance Studies scholar Richard Schechner discusses the terms make believe versus make belief, which relates also to how we stage ideology and community. Make believe is something that is staged to be false, that we can clearly decipher as fictitious. Make belief is a world or character that has been fabricated and appears to be true and genuine to the audience, and often times can’t be distinguished as fake. This make belief is a tool of persuasion that is very familiar when we think of the US president Donald Trump.

The tale of folk hero

Machiavelli’s Prince writes about political philosophy as well as the ruling strategies it generates. It would be fair to say that some of his philosophy is dark and manipulative, but at the same time surprisingly “practical” or “truthful” when compared to the political reality – even though it’s six centuries later today. When he talks about how the way things ought to be is never the way things really are, and those who incline to the former would always see to his downfall, it reminds of the immoral tricks behind political campaign, with the ultimate goal of winning. When he talks about how people should either be well treated or crushed without any opportunity of revenge, the brutality within dictatorship that happened in history would come to mind. With the Republic Machiavelli painted bear in mind, it would be an alarming journey to go through the three other materials.

Schechner distinguishes make belief from make believe by pointing out the substratum that make belief can lead people into a firm prejudice that they would celebrate, advocate, or even willingly die for. These believes are not always moral and justice. On the contrary, they often are radical, contradictory and sometimes horrible. But once they align with certain mindsets, passions and demands, they become dangerously empowered, almost poisonous.

On the other hand, Kolbert’s article explains how people are bound to their own prejudice and thus overlook most evidences that suggest otherwise. It is probably the mindset passed on by evolution through a collaborative life style and has not yet been modified in time by modern social environment. This is why proper education of criticality is of great significance, which could help us tell the truth from the fake. Unfortunately, such education still might no escape the trap of “myside bias”, as human society is never about rationality and solid science. The advancement of science itself is fueled by curiosity (and probably a wish to conquer), which is, in other words, passion.

The theory and the research both help explaining how Trump emerges as a folk hero, who break the norms and moral standards but still get praised and supported. Folk hero is the natural rule breaker fighting for a greater good, where his behaviors become demonstration of might, and might becomes right, the most forceful power.

Rehearsal, Leadership, Chorus, and Lore

Having read the book at a different time then it is today, gives the book a completely different perspective of the current situation of the world today. Simply based on the performance of political leaders. I found that Machiavelli, through his masterpiece of the prince, shows us the different types of principalities, the types of armies, the political system in Italy, and the characteristics, mannerism, behaviors, and attitudes that create the personality of the prince. Such characteristics, behaviors, and mannerism are tightly connected to what we see in Donald Trump. Machiavelli presents different principalities and different types of armies for a prince that, through a guideline of his own, he recommends the following in order to be a great leader: its better to be stingy than generous, its better to be cruel than merciful, its better to keep promises only if keeping them goes against ones interests, leaders should make themselves hated and despised because the goodwill of the people is a better defense than a fortress, a leader should undertake great projects to lift up his reputation, and finally, a great leader should choose his advisors wisely and avoid those who flatter him. Similarly, in the article by Charles M. Blow on Trumpism Extols its Folk Hero, he says of a governor named Edwin Edwards, that he had achieved what few politicians have, “transcended the political, and on some level even the rules of the workaday world, and entered the astral league of folk heroes.” Continuing to argue that people don’t agree with these politicians and do not compare themselves to them, however, the awful behavior that, including Donald Trump portrays, people prefer to relish it in the folk hero rather than in their own personal lives, and though his supporters are aware of his lying and corruption, to them, its all part of the show and the lore as Blow mentions, “they are allowing in him something that they would not allow in themselves.” Blow affirms that “Trump ascended to folk hero status among the people who like him, and so his lying, corruption, sexism, and grift not only do no damage, they add to his legend…The folk hero, wether real or imaginary, often fights the establishments, often devious, destructive and even deadly ways, and those outside that establishment cheer as the folk hero brings the beast to its knees.” Because we see this clown act, and as blow continues “Trump’s Br’er Rabbit-like ability to avert the best attempt by authorities to hold him accountable, at least for a while, only increases the chorus of applause” his greediness, selfishness, and outbursts to authority is a perfect example of what Machiavelli mentions to be a quality for a leader “better to be stingy than generous and better to be cruel than merciful.” Furthermore, as described in the performance video on how politicians use the belief/make believe “When a politician campaigns is make believe, they have been scripted, rehearsed, presented as make believe, making the voter that what they are saying is the true life… Critics who stick forks in them, who way, this is not true, to show that there is a gap between what the politician says and has said, to make believe that this is the actual social political reality” However, based on the research presented by the article Why facts don’t change our minds, it is imperative to analyze what it is presented “for their beliefs has been totally refuted, people fail to make appropriate revisions I those beliefs” Kolbert says. Kolbert affirms that the studies conducted on “confirmation bias” is a tendency that people have to embrace in order to support their beliefs and reject information that contradicts, “if reason is designed to generate sound judgements, then its hard to conceive of a more serious design flaw than confirmation bias,” but Kolbert then mentions that this leads people to dismiss evidence. Kolbert then goes presents another example by Sloman and Fernabach called “illusion of Explanatory depth” where people believe that they know way more than they actually do, which occurs by the belief of others, a trait in humans through out history meaning that we have always relied on other’s expertise. “As a rule, strong feelings about issues do not emerge from deep understanding… If your position on, say the affordable care act is baseless and I rely on it, then my opinion is also baseless… If we all now dismiss as unconvincing any information that contradicts our opinion, you get, well, the Trump Administration” Kolbert says on the human weakness of the political domain and the experiment of the toilet, as well as the danger of knowledge as community.

Del principado al gobierno de las corporaciones

Si bien El príncipe es un libro escrito para un tipo de organización política particular: el principado, en oposición a la república, muchas de las conductas recomendadas para que un príncipe mantenga su poder pueden ser trasladadas a contextos actuales para analizar, sobre todo, el poder en cabeza de ejecutivo y los poderes económicos ocultos tras él. Nuestra realidad global está circunscrita a las lógicas del capitalismo en el que nada escapa a las posibilidades de ser convertido en mercancía y en la que los estados mismos son actores fundamentales en la consolidación de negocios que favorecen intereses particulares por encima de los de los ciudadanos en su conjunto. En el príncipe, Maquiavelo recoge una serie de premisas no para gobernar de la mejor forma, sino para mantener o garantizar la existencia del principado, es decir, estas premisas buscan favorecer un interés específico, el del príncipe, no los intereses de sus súbditos. Una pregunta que podemos hacernos es: si ya no estamos organizados en principados, al menos en la mayor parte del mundo occidental, y en esta medida no es el interés del príncipe el que prima, cuáles son los intereses que priman hoy en la realidad y en el discurso y de qué manera los consejos de Maquiavelo pueden servir para favorecer esos intereses o para comprender como funcionan. En un mundo globalizado y ordenado en torno a las dinámicas económicas transnacionales ¿qué intereses protegen los Estados?, ¿de qué manera lo hacen?, pienso, por ejemplo, el actual escenario político-económico es ideal para la proliferación de lo que Maquiavelo llama “soldados mercenarios”(80) aquellos que luchan por el príncipe a cambio de un pago, si bien Maquiavelo consideraba más útil la lealtad de los soldados, en las circunstancias actuales las transacciones económicas con fines bélicos parecen ser una salida mucho más plausible. La política bélica internacional de los Estados Unidos puede ser analizada desde esta perspectiva, a la que también obedecen las alianzas entre Estados y grupos paramilitares que tienen lugar en muchos países del mundo y tras las que se ocultan intereses económicos disfrazados de valores democráticos. El espectáculo de la política tiene dentro de sus tareas materializar este disfraz. Tal vez las cinco virtudes a las que se refería Maquiavelo han cambiado, pero lo que no ha cambiado es lo que sustenta su consejo “un príncipe debe tener muchísimo cuidado de que no le brote nunca de los labios algo que no esté empapado de las cinco virtudes citadas (…). Pues los hombres, en general, juzgan más con los ojos que con las manos” y más adelante “porque el vulgo se deja engañar por las apariencias y por el éxito” (120). En las sociedades capitalistas, el éxito se mide en la ganancia económica. El discurso del éxito económico tiene la característica de ser fácilmente adoptado ¿quién no querría identificarse con una figura con poder adquisitivo, que promueve un ideal de vida caracterizado por el lujo? El príncipe ideal es, entonces, el empresario exitoso. Trump luego de haber desplegado sus habilidades gerenciales en un reality show, o varios de los presidentes latinoamericanos avalados por los gremios industriales y empresariales de sus países. El artículo del New Yorker me hizo pensar también en el éxito como creencia y en la dificultad de sobreponer a esa creencia la importancia de los valores democráticos o de la crisis ambiental o cualquier otro asunto que resquebraje el sueño del éxito económico, que deje en evidencia su naturaleza aparente.

The spectacle of the dictator

The readings for this week talk about the construction of the figure of the leader that works on the beliefs of the people in order to gain power. Machiavelli proposes that autocratic regimes are founded with a leader –prince- that creates the spectacle of power through discourse and under the figure of a strength that does not fear the opposition to its regime. In this way, we can relate to the figure of the dictator as someone that is feared and that will have the power to handle what the country needs; “The answer is of course, that it would be best to be both loved and feared. But since the two rarely come together, anyone compelled to choose will find greater security in being feared than in being loved.” This resembles the figure of what in Latin America was the phenomenon of caudillismo that was a precedent for the instauration of dictatorships and that constituted the leader capable to apply “mano dura”. We can see examples of this in the figure of Fujimori and now Bolsonaro.

Elizabeth Kolbert’s article also highlights how social interaction is what shapes our reasoning. Through these thinking systems people, for example, tend to just pay attention to the information that reaffirms their beliefs, and rejects what is contrary to their train of thought. Because of this “confirmation bias” people tend then to only listen to what satisfies the opinions they have already formed; “confirmation bias leads people to dismiss evidence of new or underappreciated threats.” Part of this system is also about relying in someone’s expertise without real verification, but only for the process of socialization. This construction of beliefs then would have more repercussion in politics when “community of knowledge” that does not really manage information become dangerous.

Charles Blow’s article exemplifies these ideas with the figure of Trump and how he transcends as a figure of the “folk leader”- very much what in Latin American is known as “el caudillo”. One important thing in the reading is how in front of the folk leader people abandon their beliefs and blindly believe in the spectacle of power. For example, we saw many white women voting for Trump in spite of the sexual assault scandals around him. In this way; “Behavior that people would never condone in their personal lives, they relish in the folk hero.” As the author says, his lying and sexism don’t damage his persona, but rather add a different dimension to his figure as the outcast, fighter of the establishment and hero. Similarly, in Peru, the dictator Fujimori constructed his persona as the savior and the only powerful one to fight terrorism. For this reason, people condoned the human rights crimes he committed, and elected him for president three times.

The Powerful Stranger

In many ways, the readings this week continue our conversations from last class around the construction of belief. In the short video “Make Believe and Make Belief,” Richard Schechner suggests that the practice of “making belief” creates a meaning that is “not endowed”; “in actually performing the rituals…these actions, these performances create the belief, a reality that people live for, celebrate, murder for…” In Elizabeth Kolbert’s article, the ritualistic, repetitive nature of this practice becomes tied to human evolution. Following the experts interviewed for the piece, Kolbert writes, “Reason developed not to enable us to solve abstract, logical problems or even to help us draw conclusions from unfamiliar data; rather, it developed to resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups.” Confirmation bias is cited as one of the examples of this phenomenon; according to the Gormans, the experience is physiological; “suggesting that people experience genuine pleasure––a rush of dopamine––when processing information that supports their beliefs.” This is an interesting perspective to establish a dialogue with in terms of our ideas about politics and the mobilization of affect.

Indeed, the political trajectory of our country is enough cause to make one question the limits of reason. Blindness once again comes into play; Kolbert’s article discusses “myside bias,” which suggests that we are adept at spotting the weaknesses in other’s arguments, but that “the positions we’re blind about are our own.” In Mercier and Sperber’s terms, this does not have to do so much with percepticide –an active disavowal– but rather how we are inherently socially wired, “[it] reflects the task that reason evolved to perform, which is to prevent us from getting screwed by the other members of our group”; significantly, there is still an effacement of recognition on the part of the subject, that has been tied to a lack of acknowledgment of complicity and responsibility in our previous conversations (later on, Sloman and Fernbach do point to blindness’ extreme manifestation that does include active disavowal, stating “If we all now dismiss as unconvincing any information that contradicts our opinion, you get, well, the Trump Administration”). Mercier and Sperber trace the first instance of this blind behavior from the time in which humans lived in hunter-gatherer formations, suggesting that reason often seems to fail us because “the environment changed too quickly for natural selection to catch up.” I would contest this conception of belatedness because reason has evolved with changing historical circumstances; take Foucault’s tracing of the development of a neoliberal reason for example, based on homo economicus as an entrepreneur of himself. While Foucault saw, through neoliberal governmentality, the possibility for an increased individual autonomy, in the contemporary situation we see how this reason has mutated further into one that champions self-sufficiency and competition above all else, eroding relational bonds and communitarian values such as care in the establishment of social relations. This too has a connection to the original concern of not “getting screwed by the other members of our group.”

One of my critiques of Kolbert’s article is its focus on a scientific-rational ordering of the world; “Science moves forward,” “the goal [is] promoting sound science,” which undermines other knowledges and possible solutions for the contemporary reality. Charles Blow raises a smart counterpoint to the strategy of calling Trump a liar (one that obviously has not yielded much success) because “the rules don’t apply to the folk hero.” In fact, many times, breaking the rules is positively reappropriated into challenging the establishment in Trump’s rhetoric; he plays the role of the “powerful stranger” (24) in Machiavellian terms and is able to make a practical use of his bad behavior; “It is essential…for a Prince…to have learned how to be other than good, and to use or not to use his goodness as necessity requires” (Machiavelli 79). Blow argues that the opposition’s focus should rather be on dismantling Trump’s figure as such a “hero”: “the great miscalculation people make in trying to understand Donald Trump and the cultlike devotion of the people who follow him is that they continue to apply the standard rules of analysis…How does one fight a fiction, a fantasy?” Blow’s article allows us to perceive how Trump has effectively mobilized the strategies of persuasion and perception present in Machiavelli’s text. He emphasizes how “the only vulnerability the folk hero has is an exposed betrayal of the folk”; Trump realizes the importance of keeping his base’s support; he “fawns” over them, and they reciprocate. Trump also demands loyalty of his “court”; the musical-chairs like turbulence that his Cabinet and key White House posts have experienced through constant resignations and replacements clearly speaks to how “the choice of Ministers is a matter of no small moment to a Prince” (Machiavelli 116).

Machiavelli argues that the attainment of a Civil Princedom lies in the fortunate astuteness of the leader; fortunate, because the circumstances have to be right, but astuteness, because the leader needs to secure the “favour of the people or of the nobles” (52). Machiavelli bases the relationship between ruler and subject on favour, affect, stating that the Prince’s subjects should, at all times, “feel the need of the State and of him, and then they will always be faithful to him” (56). Trump’s self-centeredness, and how he performs it in an “I/me”-based discourse and rhetoric through the repetition of his own accomplishments, is then a mobilization of this performance that seeks to maintain the loyalty of his following, and consequently, his own power.

El Príncipe latinoamericano

El Príncipe latinoamericano

Los materiales de esta semana sirven para mostrar de qué manera las propuestas teóricas de El Príncipe de Maquiavelo siguen más vigentes que nunca en el ágora político contemporáneo. En primer lugar, en lo que a la espectacularidad de la política concierne, Maquiavelo es insistente en resaltar que “no es preciso que un príncipe posea todas las virtudes citadas, pero es indispensable que aparente poseerlas”. La idea de la política como una apariencia, en el sentido de un aparecer mediático que se planea como una ficción pero que se escenifica como una verdad, es también lo que subraya Richard Schechner cuando propone que los políticos hacen creer y creencia (make belie(f)(ve)) a partir de la repetición performática de una escena y un discurso “more artificial than a halloween movie”. Pongo por ejemplo los actos de campaña del actual presidente de Argentina hasta diciembre, Mauricio Macri, quien construyó una estética de la política como una fiesta con música y baile. Opuesto al tono más discursivo y serio de Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, que una porción de la sociedad despreciaba debido en parte a la invectiva mediática contra ella, Macri propuso la política como un escenario no-discursivo de festejo, a partir de un slógan publicitario irrealizable en la práctica, en gran medida porque sería imposible demostrarlo empíricamente: “unir a los argentinos”. Acaso el video sea un buen ejemplo de cómo políticos ponen en escena algo que saben que es una ficción pero que lo constituyen como creencia a partir de la repetición performática.

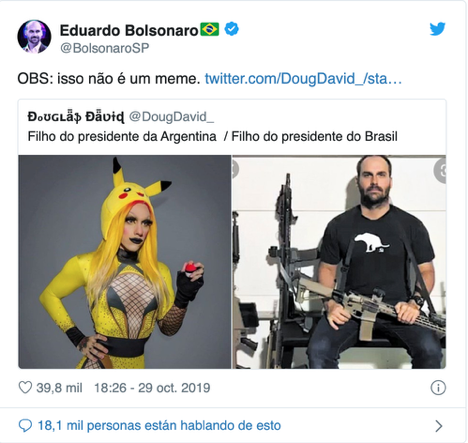

Por otro lado, Maquiavelo en el capítulo XXI afirma que el Príncipe debe hacer o aparentar grandes hazañas para ser estimado, como Fernando de Aragón, quien “hizo la guerra cuando estaba en paz”, idea que se conecta con la afirmación de Charles M. Blow de que cuando el líder alcanza el “folk hero status” cualquier acción mediática en apariencia aberrante para el sentido común de una sociedad en otro contexto sólo ayuda a aumentar su leyenda. Esto lo podemos observar en el meme que compartió el clan Bolsonaro comparando al hijo de Jair Bolsonaro con el del presidente recientemente electo de Argentina, que practica cosplay. Una imagen teñida de homofobia, transfobia y machismo y que en cualquier otro momento hubiera sido unánimemente repudiada por la prensa y la diplomacia de Argentina y Brasil, para los seguidores de Bolsonaro, que festejan sus “hazañas mediáticas”, ayuda a contribuir con su admiración al personaje performático de macho militarizado.

Why folk heroes are on the rise?

Schechner claims that Make believe is when you know what you perform does not exist in reality and Make belief means making people believe, making a certain reality by, i.e., a religious activity. In real life, Politicians use the fluidity between these two methods to form people’s prejudice against something. In my opinion, the biggest difference between the two is whether the audience participates in the performance, that is, whether they are specactors: i.e. in political spectacles, if the voter is convinced by the authorities make belief, they vote for the politicians, Machiavelli is the first one who make the process of Make belief clear in the political field: in his opinion, education in those past centuries has only given citizens idleness and weakness, which makes them lack of decency, And they don’t have the love of freedom as they were republicans, so the politicians are allowed not to be good ( in the Christianity sense) anymore.

Kolbert explains the citizens’unreasonable response to political fiction from the perspective of cognitive behavior studies. She thinks Sociality is the key to the question because human beings rely on cooperation and highly depend on others’ expertise. As a result, there is no sharp boundaries between one person’s idea and knowledge and those of other members of the group. Once formed, a certain impression is remarkably perseverant, even when their beliefs has been refuted, people fail to make an appropriate revision in those beliefs. Because people have “confirmation bias” in collaborative works in cognitive mode and Myside bias in personal cognitions. In Kolbert’s words: the Environment changed too quickly for the natural selection to catch up so it is easier for people in the society to be trapped in fake news and crazy politician fandoms.

The other article explains why the specactors are still actively involved while it is obviously fraudulent. For supporters, what they never condone in their personal lives, they relish in the folk hero. For political figures like Trump, sexism、 lying、 corruption only adds to his legend. Blow’s article starts with a case study about fandom and tells us the real reason behind these paradoxes: He cited the example of Monkey King who is a hero but also a misbehaving child who only needs a firm hand and a sense of purpose to come good, and tries to explain the supporters intention behind their ridiculous behaviors.

Machiavelli, The Prince

Richard Schechner, “Make Believe and Make

Belief” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YG6fMnH17GU)

Elizabeth Kolbert, “Why Facts Don’t Change Our

Minds” (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds)

Charles Blow, “Trumpism Extols it’s Folk Hero,”

NYT, 4/8/19, (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/07/opinion/donald-trump-trumpism.html)