by Desiree Fernandez

Since ancient to postmodern theatre, we, as theatre scholars and artists, have been striving to improve what theatre is and what theatre should be and do. Theatre was recognized as ritual, as a practice for change, or celebration, or even advocacy for something, whether that be resources or action. In a postmodern era, we are still fighting for rights of people who have been colonized and oppressed by those who still benefit from their ancestor’s actions. Beyond being a tool to entertain or to teach, theatre should be a vessel, an “incubator” (Parks 4) to create new perspective, alternate histories, and allow bodies to decolonize and recover from trauma within their ancestral memory stored in DNA. By looking at performances from Guillermo Gomez Peña, we can then discuss how performance can be used as a way to decolonize and create new history, a reclaimed self. I am interested in body politics and how through political protest, bodies transform from objects to subjects and back again.

Peña’s Mapa/Corpo 2 is an example of how theatre is being used as an incubator to change our society’s opinions and functions of diverse bodies based on ethnicity, race, gender, sexuality, ability, and size. A new truth is being created on stage and actors are standing in for characters who aren’t actually there, the post-colonial subject stands in for the colonized, a person who has been oppressed or discriminated based on race, gender, ability, or even size.

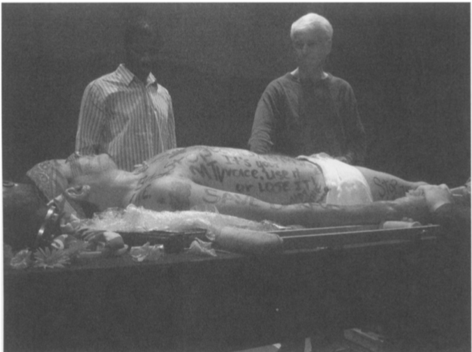

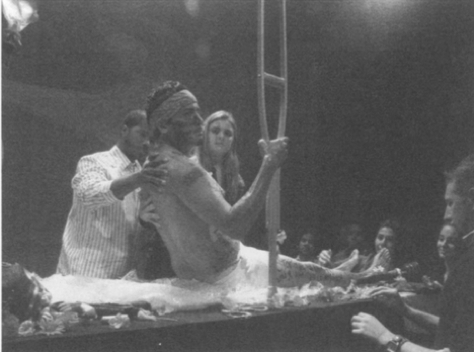

Audience members in Mapa/Corpo 2 becoming involved in the performance piece. Audience members used bodies of performers as canvases as well as helped them relieve pain and to even move. Seda and Patrick 2009.

This is exactly what is occurring during Guillermo Peña’s Mapa/Corpo 2: Interactive Rituals for the New Millennium, a performance piece that allows the participation of the audience to help those characters emancipate from colonization, trauma, and violence.

When both bodies have been decolonized with the audience’s help, the performers look each other in the eyes, as if recognizing and acknowledging each other. The performers’ bodies in Mapa/Corpo 2 become La Pocha Nostra’s artistic canvas. They function as intentional instruments of artistic agency that display the effects of colonization and violence. Thus, the bodies represent the memory of violence against the Other; they create a narrative of resistance to violence and colonization. This resistance can be understood from the multiple perspectives of gender, ethnicity, and nationality. If, as Richard Schechner has argued, “There are no clear boundaries separating everyday life from family and social roles or social roles from job roles, church ritual from trance, acting onstage from acting offstage, and so on, ‘the per formers’ genders and multiethnic backgrounds also contribute to the overall meaning of Mapa/ Corpo 2’. Thus, the individual body becomes emblematic of everybody that has endured pain, violence, discrimination, and colonization. In other words, the performers’ bodies play a vital role in this cross-cultural analysis of violence and colonization in which art becomes a holistic weapon aimed at decolonizing the body politic. Seda and Patrick 139

In this performance, bodies become objects that represent subjects that need to be decolonized. Peña is making a comment that by witnessing, you are taking responsibility to what has and will happen to these people. Therefore, it is only with action by those who have power (the audience) that these people can be relieved of oppression, trauma, and colonization. Though not to forget, these decolonized people will remember a new version of their existence henceforth. This memory and experience will rewrite what is their past history.

In Guillermo Peña’s Mapa/Corpo 2: Interactive Rituals for the New Millennium, everyone in the performance space is involved in creating a new history for the artists and the people the artists represent. “This is evident from the moment the audience enters the performance space and sees two bodies lying motionless on gurneys. These are part of a visual code that refers to pain and, simultaneously, to healing. The actions throughout the performance unfold as a metaphorical healing ritual enacting the decolonization of the bodies lying on gurneys” (Seda and Patrick 135).

When the acupuncturist begins to insert needles topped with small flags of occupier countries, the woman’s body on the other gurney becomes a metaphor for colonized and occupied territories. [I]t becomes clear that the fear and pain caused by colonization and the violenced inflicted on the bodies by means of the weapons has left on them without verbal language. The performance aims to restore voice and agency to the suffering, colonized bodies through the audience, as they help to heal the bodies by writing on them and removing the needles… By removing the needles from the woman’s body and writing on the man, the audience engages in a personal and communal act of ritualistic healing of the body politic, empowering themselves. Seda and Patrick 136-139

Through witnessing the trauma and harm of bodies, audience members are more likely to carry that empathy they feel within their own bodies to the outside world. New stories and perspective of both the performing and the witnessing will help rewrite the cultural memory of these diverse bodies in society. The audience member was an observer, never immersed, blinded to the suffering in order to feel relief and comfort. Colonization occurs when there is a restriction on the body, an inability to look or act a specific way according to the rule or conformities set on by society or the colonizer itself. Therefore, decolonization is a political movement allowing the individual agency and citizenship, these bodies are no longer objects but subjects of society.

Works Cited

Parks, Suzan Lori. “Elements of Style.” The America Play and Other Works. Theatre Communications Group, 1995. 6-18.

Seda, Laurietz, and Brian D. Patrick. “Decolonizing the Body Politic: Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s ‘Mapa/Corpo 2: Interactive Rituals for the New Millennium.’” TDR (1988-), vol. 53, no. 1, 2009, pp. 136–141. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25599456.

3 Key Terms:

Make Believe vs Make Belief

Archive (what is remembered in the body and in “history”)

Emancipation