keywords: duality, coalescence/dissipation, performance/politics, cyberobjects, trans-spacetime

Working from Jacques Rancière’s description of what constitutes politics proper, Étienne Balibar, in his book Politics and the Other Scene, argues that there is a paradox inherent in the predication of politics on “the part of no part.” The part of no part can neither be a subject in nor of politics; therefore, the part of no parts, the ‘have-nots’, existence, which is the condition of the possibility of politics, is at the same time the condition of its impossibility. Using Rancière’s formulation as a point of departure, Balibar advances three theses: all identity is fundamentally transindividual (it is a bond validated among individual imaginations); rather than identities, we should speak of identifications (no identity is ‘once and for all’); every identity is ambiguous (no individual has a singular identity). Interpreting the title of Balibar’s essay along these lines, I believe that what Balibar was getting at was a formulation of ‘politics’ and the ‘other scene’ as mutually constitutive and codependently materializing economies: the ‘other scene’ is distinctly named apart from ‘politics’ and simultaneously its conditions of emergence. They are not isolated events, strung together by narrative threads, one acting and the other reacting: endlessly. They are circulations of energies, coalescences and dissipations, cool fogs and hot, dense balls of gas. We cannot mean politics without also meaning performance; we cannot mean appearance without also meaning disappearance—what we have, then, is surplus rather than positive and negative; duality rather than binary.

My reference to ‘duality’ is based on the quantum-mechanical property of being regardable as both a wave and a particle. There is much more we can do with more recent quantum theory concepts, but this early-discovered property made a significant impact on the field of physics, and I think it can have similar effects on understandings of politics and performance in discussions of the digital (and the posthuman in general, but that’s for another essay). Using ‘duality’ as an anti-binary framework, it is interesting to discuss politics and performance as two different measurements of the circulation of power, of the economy of affects and the sensory, of the coalescence and dissipation of bodies oriented towards desires.

Jacques Rancière, in his book titled Politics of Aesthetics, introduces us to his concept of ‘the distribution of the sensible’: the system of divisions and that define, among other things, what is visible and audible within a particular aesthetico-political regime. For Rancière, the essence of politics consists in the distribution of the sensible, asserting that these aesthetic regimes are simultaneously theoretical discourses—that is, sensible reconfigurations of the facts they are arguing about. The distribution of the sensible is one interesting articulation of the energy circulations and materializations of politics and performance, which demonstrates the systematic definition of divisions and boundaries, rather than its predication on ever-fixed divisions and boundaries. The essence of politics (performance) is, then, perception, which we feel as excitations of senses and affects—not isolatable phenomena, but economies, series of practices (Balibar here, again). To move against a distributive understanding of performance (politics) is to contribute to the maintenance of what Diana Taylor calls ‘percepticide’: The American Way.

Chantal Mouffe, in her book titled Agonistics: Thinking about the World Politically, refers to ‘politics’ as the ensemble of practices, discourses and institutions that seeks to establish a certain order and to organize human coexistence in conditions which are always potentially conflicting—there is a reduction of passions and a distillation of identities. It is not, for Mouffe, the prime task of democratic politics to eliminate passions or to relegate them to the private sphere in order to establish a rational consensus in the public sphere. Rather, it is to sublimate those passions by mobilizing them towards democratic designs, by creating collective forms of identification around democratic objectives. The celebration of politics of disturbance, according to Mouffe, ignores the “other side of the struggle” (another scene; and, another duality). What Mouffe wants to get across, then, is that to predicate an articulation of politics (performance) on disappearance, absence, nothingness; or, to conjecture that politics and performance (often assumed to be a regime vs. a resistance), appearance and disappearance, power and powerlessness, operate as binaries is to “eliminate the passions,” to define borders between bodies, ignoring any leakage, any transference, any bleeding. Those passions, rather, demand our orientation towards them, as an assembly, as a collective body.

In her book, Performance, Diana Taylor argues that “people absorb behaviors by doing, rehearsing, and performing them” (13). Performances “operate as vital acts of transfer, transmitting social knowledge, memory, and sense of identity through reiterated actions” (25). Taylor advocates for what I’ll refer to as ‘trans-spacetime’ in her engagement with the digital, explaining that “the digital has become an extension of the human body”: we all have ‘data-bodies’ (108). Taylor concludes that “Experience can no longer be limited to living bodies understood as pulsing biological organisms. Embodiment, understood as the politics, awareness, and strategies of living in one’s body, can be distanced from the physical body” (138).

Working through these theories in constellation, I want to introduce stimulating concepts from Stephen Hartman’s essay “The Poetic Timestamp of Digital Erotic Objects.” In this essay, Hartman describes ‘cyberobjects’ and ‘technogenesis’ as constitutive elements (performances) of ‘screen relations’ in what I’ll name ‘cyberspacetime’. Objects in cyberspacetime are ‘introjected’ by someone—that is, one comes to identify with a cyberobject and takes it into oneself—and, as groups interact with these cyberobjects, these objects become ‘groupal objects’. In other words, these cyberobjects become the basis of a ‘technogenesis’: what Mouffe would see as a mobilization of passions. In the spirit of Butler’s acknowledgement of vigils as performative assemblies, I want to look at two performative assemblies in cyberspacetime, which mobilized affects and passions towards a democratic design (specifically, mutual support and interdependence).

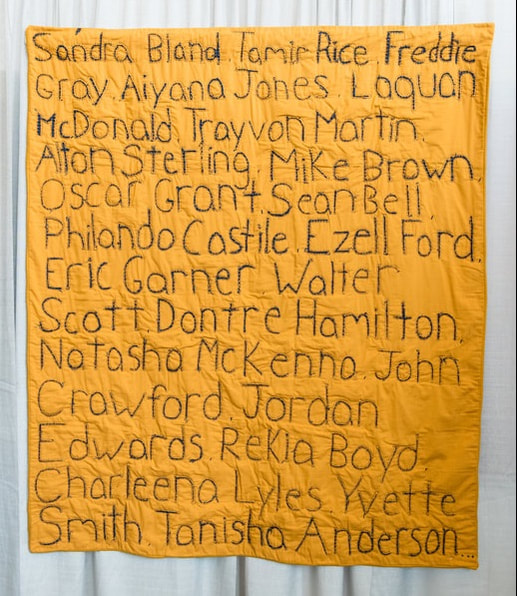

The SayTheirNames Movement and the MeToo Movement are examples of performative assembly/collective politics which grew in the soil of cyberspacetime to spread roots in what I’ll name ‘trans-spacetime’. SayTheirNames was borne from The Social Justice Sewing Academy, performed in the sewing and embroidering of a quilt with the names of Black people who have lost their lives unjustly, often as “invisible victims of police brutality” (artist: Sara Trail 2017). The idea was inspired by the social media hashtag #sayhername; likewise, MeToo blossomed from the viral #metoo hashtag which brought a vital conversation about sexual violence to national attention. In circulations of affective economies in cyberspacetime, performative assemblies formed which were oriented towards democratic designs.

In her articulation of this process of orienting our body, Sara Ahmed comes to define a larger picture of Queer Phenomenology. She tells us that the queer was always already in the phenomenology; it is a matter of orienting ourselves towards it. For Fred Moten, the queer in the phenomenology is the dialect in the dialectic; for Diana Taylor, it is the ‘spect-actor’ in the spectacle; for Bertolt Brecht, it is the pleasurable and entertaining in the terrible and never-ending labor which should ensure one’s maintenance. Orienting towards these things, we create those ‘desire lines’, which Ahmed borrows from landscape architecture to describe the formation of new norms.

These repeated behaviors, these performances, are found in Hannah Arendt’s theorizing of actions in the ‘space of appearance’ in her book The Human Condition. Judith Butler, in Notes Towards a Performative Theory of Assembly, rethinks ‘action’ as well as the discursive and performative practices shaping subjecthood as spaces of appearance, where assemblies come to materialize both matter and meaning, which are always performative. Butler engages with Arendt’s theory, acknowledging that she shows that “the body or, rather, concerted bodily action—gathering, gesturing, standing still, all of the component parts of ‘assembly’ that are not quickly assimilated to verbal speech—can signify principles of freedom and equality” (48). Both Arendt and Butler use the language of a kind of thermodynamics in describing ‘power’ and ‘popular assemblies’ (respectively), highlighting their understanding of the experimental nature of concerted action as well as their understanding of the role of environment in the process of meaning, mattering, materialization. The environment, the space of appearance, is historicized, and is a coalescence of historicized bodies in concerted, historicized action, predicated on the mobilization of the passions, the orientation towards collective identifications and desires.

The space of appearance is a new spacetime (which is also cyberspacetime): one that is inherently a trans-spacetime (in the sense of the ‘trans-‘ prefix, meaning ‘across’, ‘beyond’, ‘changing thoroughly’, and also in the sense of my own personal orientation towards inscribing the trans body with power). This trans-spacetime is seen in Arendt’s “Irreversibility and the Power to Forgive” and “Unpredictability and the Power of Promise.” It is also seen in Balibar’s assertion that all identity is trans-individual, and in Diana Taylor’s “acts of transfer.” SayTheirNames and MeToo show that the space of appearance also must acknowledge a cyberspace of appearance with ‘actions’ or ‘performances’ mobilized around cyberobjects. These introjections of cyberobjects by groups is also performative assembly, orientation of a collective body, mobilization towards democratic designs. To conclude, I would like to reintroduce ‘duality,’ as my central thesis is that performative assemblies, in our time, are not constituted separately in the cyberspace of appearance and the space of appearance, but that these are actually just different measurements of a trans-spacetime, and are mutually constitutive and deeply entangled: like politics and performance, like appearance and disappearance, like coalescence and dissipation, like matter and energy.

- Sara Ahmed, “Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology,” in GLQ: a Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies

- Fred Moten, Black and Blur

- Diana Taylor, Performance

- Diana Taylor, “Acts of Transference” in The Archive and the Repertoire

- Etienne Balibar, “Three Concepts of Politics: Emancipation, Transformation, Civility” in Politics and the Other Scene

- Jacques Ranciere, The Politics of Aesthetics

- Chantal Mouffe, “What Is Agonistic Politics?” and “Agonistic Politics and Artistic Practice” in Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically

- Bertolt Brecht, “Short Organum for the Theatre” in Brecht on theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic

- Hannah Arendt, “Action” in The Human Condition

- Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly

- https://metoomvmt.org/about/#history (MeToo History & Vision)

- https://metoomvmt.org/media/ (MeToo Media)