Michele Foucault was well on his way to the formation of his theory of biopower in the historical layout of public execution in Discipline and Punish. His move from execution as a public spectacle to, “punishment, then will tend to become the most hidden part of the penal process,” is reflected in his theory of biopower much later as the shift from the almighty monarchical sovereign to the nation-state sovereign (Foucault, 9). From this we can draw that the state’s power, as it relates to punishment, is much more limitless; before, when the sovereign could “let live and make die,” the power ended when the sovereign made die, however the state shifts to a “make live and let die” power dynamic that extends the state’s power to have a psychological hold over the public in a regulatory fashion through the “invisibility” of punishment. It is still happening; we just don’t see it. Or rather, we now choose not to see it.

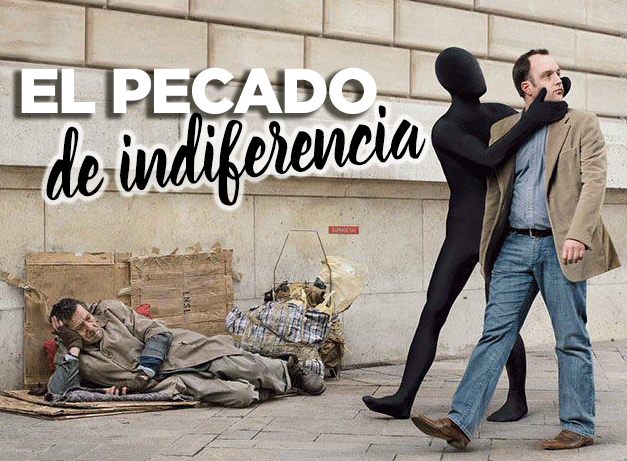

Diana Taylor states (within the context of Argentina) in Percepticide that “Signs indicated what the population was to see and not to see,” creating a clear delineation between the public and private sphere, and that which is private is also incredibly dangerous and violent (Taylor, 119). “Spectacles of violence rendered the population silent, deaf, and blind…To see without being able to do disempowers absolutely. But seeing without the possibility of admitting that one is seeing further turns the violence on oneself. Percepticide blinds, maims, kills through the senses” (Taylor 123-124). The public exaction of biopower from the days of old enacts a sort of transference to become an invisible and powerful monster, exacting itself now on the population where “if you see something, say something,” is a trap. If we say something, it becomes real. And if it becomes real, we will have to continue to do something about it.

I believe that Percepticide manifests itself differently depending on the particular political arena. Perhaps this idea of “not seeing,” can be looked at in a perspective way through Rene Girard’s concept of the scapegoat mechanism. Girard looks at persecutions which are, “acts of violence, such as witch-hunts, that are legal in form but simulated by the extremes of public opinion” (Girard 12). He traces the genealogy of the scapegoat through the context of religion and animals – using the example of the sacrifice. Sacrificial “victims” – which, in this framework are not necessarily victims – are meant to end the cycle of violence in a crisis. They are sacrificed without the fear of reciprocity. This particular intensity of public opinion to create the scapegoat which ends in collective forms of violence is contingent upon the similarly violent delineation between public and private spheres through the enaction of biopower, of seeing and not-seeing, and through the (hidden) spectacle of the state. In this case – I’m left with the question of narrative and language. If punishment is “hidden,” if the power of the state is left to live on through the invisible threat of punishment and torture, if the sacrificial scapegoat must be created to avoid further crisis – what type of narrative is required to sustain this? And, is there a narrative – is there language – sufficient enough to undo this mechanism once it is mobilized?