Through this interactive map, the invisible and the hypervisible overlap. While the selected sites differently contend with the notion of political spectacle—ranging from violent events curated by State actors and public acts of resistance to deliberate political omissions within the regime of visibility—their critical consideration might orient us towards an understanding of the forces which order our sensible relationship to the public sphere and which transform spaces within a collective imaginary. The consistent consideration of the technologies which facilitate and expand political spectacle (our map is not an exception) points to the idealized potential for global accountability while making us painfully aware of the persistent reenactment of historical flows of power. Cameras, televisions, computer screens, satellites, fiber optic cables, among many others, all work to challenge or even dissolve our perceived notions of public/private, visible/invisible. They help us understand that hypervisibility and invisibility are co-constructed, and the cases examined here show us that both can be manipulated for oppressive as well as emancipatory ends.

We conceive this map as an element capable of gathering multiple voices that signal, denounce or evince a political reality that some political actors want to make invisible. We agree with Rancière’s perspective in “The Intolerable Image” and seek to provoke in the viewer, after they explore our map, a call to action. We want whoever approaches this map to be complicit in the images selected, to get them involved, on the one hand, and to challenge their capacity for action on the other: “The mere fact of viewing images that denounce the reality of a system already emerges as complicity with this system (…) It tells us that the only response to this evil is activity” (Ranciere 2004, 85). In this map, not only spaces of resistance are captured, but we also chose to make visible spaces of torture and of the violation of human rights. They are, then, spaces that we consider worth showing to also make a complaint. These spaces exist, they are there, they do not cease to exist because we refuse to see them.

The images rendered here are “screenshots” of various digital “sites”: social media sites, digitally-mapped geographic/cartographic sites; sites of struggles, sites of harm, sites of empowerment. Reproducing images vis-a-vis “screenshots” from such an array of “sites”, and playing with the term “site” itself in order to expand our conversations around “spaces of appearance” or “sites of assembly”, should be interpreted as a performance of one of the central arguments in discussion of the “spacetime of political spectacles”; that is, our “real” and “digital” spaces/sites and times/temporalities (here, referred to generally as “spacetimes”) are closely entangled and deeply imbricated. Our social movements and, more generally, our movements as social actors—which we are thinking along the lines of Diana Taylor’s “spect-actors” (by way of Boal)—are performed in a mixture of analog-digital spacetime. In our various interpretations and appropriations of the term ‘site(s)’ (alongside those terms we wish to analyze or complicate through a sort of metonymic play/performance), we see just how mutually effective and constitutive these realms are. This “metonymic play” is intended to point to the various ways the terms “site,” “cite,” and “sight” interact and come into contact with each other, rubbing together, causing friction, generating new insights, and composing the ways through which the spacetime of political spectacle can be understood. Sites are rendered here and reinterpreted through this understanding, allowing us to think more critically and creatively about how our movements may be both emboldened and thwarted within spacetime.

Although satellite images and security cameras create an illusion of global visibility, there are still streets that you cannot walk through on Google Maps, streets where bodies are detained, concentrated, and made invisible. Under constant surveillance, people are seen in the political spectacle but their voices are muted and oppressed. The act of mapping the locations that power apparatuses prefer to blur turns the gaze the other way around, making visible spaces of political and humanitarian violence. Many of them are in the Xinjian region of China, where cyberspace control led to physical detention, underscoring how political spectacles are transformed under surveillance and the Internet, blurring the lines of the digital and the real, of what is left and what is extended from the body in its digitality.

The goal of creating an interactive map was to utilize neoliberal tools of consumption as a method for subverting the status quo. Google Maps has been a major agent of the dissolve between physical and digital space through Street View: now we can transit on our computers and our phones any corner of the planet… seemingly, though this is misleading. Neoliberal times allow for the privatization of public spaces and the transformation of matter into data, but populations are starting to take back the maps and the spaces that they transit day in and day out. Google is also particular in offering users the ability to “Report a problem” and “Suggest a change” on a map, that is, it is also crowdfunded in principle, and this one feature makes the map malleable, a potential tool for shaping the world around us. What happens when insurgents and protestors, infuriated with their government and their context, decide to rename their public landmarks through collective action? How can rebellious citizens take back ownership in the face of a political spectacle? How can they make their popular will visible to the eyes of the state and the international community? Maps, then, are not just place markers: they become spaces of appearance, a democratic battlefield, a site for change, the inauguration of a brave new world. These maps are ever-changing, growing bigger every day, and our role as spectators can be more active and action-minded by using the tools within hands reach for airing out political dissent.

We present this interactive map because we consider it a useful tool for the collective construction of a historical/critical panorama, to think through the spatiotemporal conditions of political spectacles, to identify patterns of use among disparate political actors—of politicians and resistance actors, seeing as how particular uses of the networks in political campaigns, or similar strategies of resistance and protest, are repeated in different times and places, as is the case of sex strikes. We invite our peers and collaborators to interact, discover, and add to our map as the sites of political spectacle are made hypervisible for the world to know.

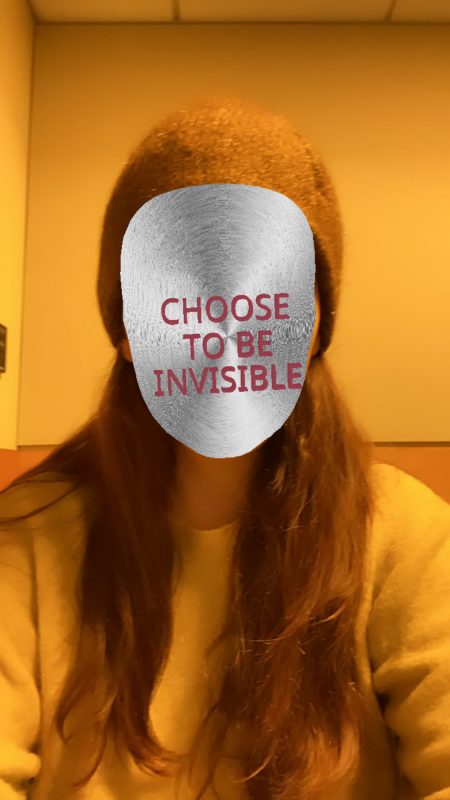

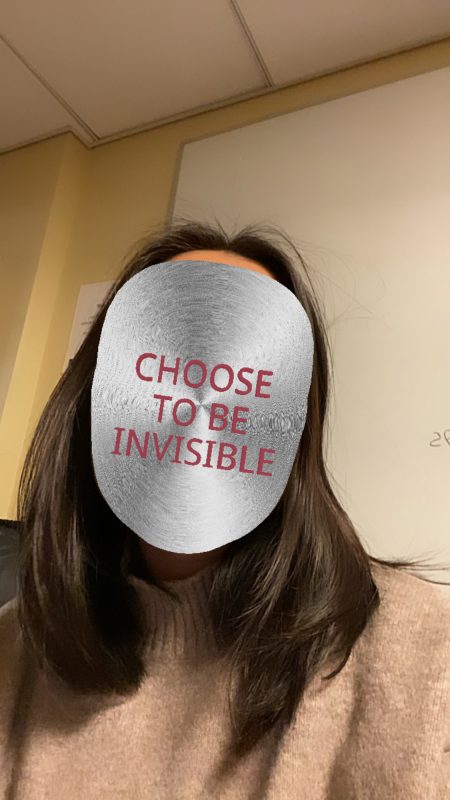

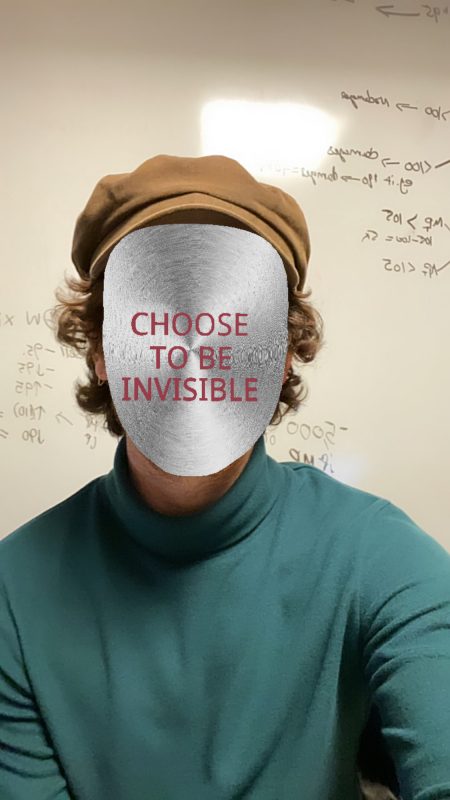

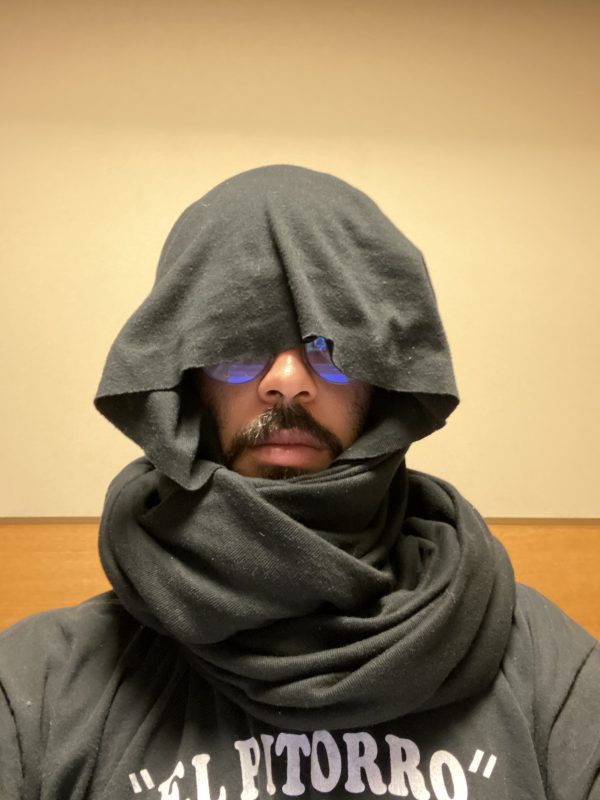

Another interactive tool that our project presents is a Facebook filter for those who want to use their digital images as a political act. In the time when biodata can be accessed without any consent, the use of our own faces to express opinion can be regarded as gaining back the right and decision to be in/visible. We acknowledge that this feature still works on the face recognition technology but, at least, in this case, you can let it be captured for a project that you are aware of. Follow this link to try the mask now.

Cyberspace in terror

With the entrance of surveillance and Internet political spectacle has acquired a new digital stage. Interaction in the cyberspace create the digital extensions of bodies that can be used both to regulate and empower people. Anel will discuss the perspectives of the cyberspace in the case of repressive regime against Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in China.

Anel Rakhimzhanova

“No / yo no quiero una vida mejor / yo quiero una vida nueva”

Visibilizar espacios de resistencia y denunciar espacios de violación de derechos humanos en relación a la migración es un tema urgente que merece nuestra atención. Lejos de pensar en un migrante pasivo, mi visión es la del migrante como sujeto político, capaz de resistir, organizarse y sobrevivir.

Laura Rojas

Lisístratas contemporáneas

La huelga de sexo o huelga de piernas cruzadas, práctica política utilizada por mujeres de distintas comunidades en tiempos y lugares diferentes, puede ser leída como una transgresión de los órdenes políticos, sociales y familiares establecidos, además del uso y distribución de los espacios públicos y privados. Mediante la aparición en la esfera pública de los cuerpos deseantes de las mujeres, la huelga de sexo participa de la discusión sobre el lugar de las emociones y los afectos en el ámbito político.

Carolina Dávila

Espectáculos Fujimoristas: Televised Control and Dehumanization in 1990s Peru

Throughout the 1990s, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori used television broadcasts to deliver a calculated narrative of dominance over the widespread violence of the time. The cases considered depict his careful curation of televised political spectacle and the process of visual dehumanization for those deemed “terrorists” by the State, those engaged in “criminal” as opposed to “legitimate” violence.

María Paz Almenara

Thinking through “Cyberspacetime”

In this section, Henry traces the hashtags of social movements through an analysis of the “cyberobject” to demonstrate concepts of “technogenesis,” “mixed realities,” “cybermourning,” and to expand and challenge notions of the spacetime of political spectacle with considerations of the digital. This analysis shows how social movements and assemblies forming around cyberobjects, such as the hashtag, complicate the boundaries we have drawn for ourselves between “the digital” and “the analog,” expanding our understanding of political spectacle and the role of the “spect-actor.”

Henry Wilcox

Renaming Public Spaces in Neoliberal Times

In the ever-increasing privatization of public spaces in the wake of neoliberalism, insurgent populations are re-appropriating these spaces by renaming them on Google Maps. This inaugurates spaces of resistance to which subsequent protests return to and invoke, melting hegemonic authority’s control of public spaces, and sparking new modes of public resistance through digital renaming practices.

José Figueroa

Table of Contents

1. Renaming Public Spaces in Neoliberal Times

2. Espectáculos Fujimoristas: Televised Control and Dehumanization in 1990s Peru

3. Lisístratas contemporáneas

4. Thinking through “Cyberspacetime”

5. Cyberspace in Terror

6. “No / yo no quiero una vida mejor / yo quiero una vida nueva”

7. Works Cited

Renaming Public Spaces in Neoliberal Times

Political spectacles occur anywhere there is a seat of power and a political actor willing to take over the stage. Therefore, the entire world can be a stage, if we follow the adage, and the space of politics (from above and from below) can happen anywhere, anytime. However, power relations intersect every space that we transit, and so too do power relations set the rules for the space of political spectacles as much as displays of resistance. In neoliberal end times, spaces deemed public are increasingly superseded by private interests as state governments double down in their efforts to criminalize protests, reducing the amount of space available for dissent, incarcerating bodies that breach the state’s established limits. At the dawn of an era defined by more dissidence in the face of neoliberal austerity, how can populations take back space in the face of a political spectacle? How can the digital help expand the space for pushback?

Certain spaces deemed the seats of power can be used for the reversal of power. In San Juan, Puerto Rico, la Fortaleza—or the governor’s mansion—was constructed in the XVI century, and is the oldest executive mansion in continuous use in the New World; even after the transfer of power from Spanish to American imperial powers, the large mansion still serves as a bulwark of colonial authority, the centralization of power. Similarly, plaza Baquedano in Chile—commonly referred to as plaza Italia—in the center of Santiago has had many names across the centuries, including plaza Colón (named so after Christopher Columbus), because of which we can affirm that spaces, especially in their names, are symbols of power, authority, zealously protected by the state. What happens when these sites are taken over by massive demonstrations, rebellious insurgencies, and attempt to wrest power from the state, to take back their public spaces?

Following Arendt (1998), the space of appearance is a space (real or imaginary, physical or digital) in which one subject appears intelligible in front of another (or others), and there is a mutual recognition of peoples coming together for a political goal. Butler expands this space of appearance to include noncitizens by claiming that bodies signify in excess of discourse, therefore, offer a space of appearance simply by being there, by assembling and performing their precarity. To take overrun Old San Juan and calle de la Fortaleza, to completely envelop plaza Italia with the largest political demonstration in Chilean history, means “to lay claim to a certain space as public” (Butler 70) and offers an ampler space of appearance in the face of neoliberal grievances:

So when we think about what it means to assemble in a crowd, a growing crowd, and what it means to move through a public space in a way that contests the distinction between the public and the private, we see some ways that the bodies in their plurality lay claim to the public, find and produce the public through seizing and reconfiguring the matter of material environments; at the same time, those material environments are part of the action, and they themselves act when they become the support for action.

Butler 2015, 71

Arendt opened the stage for a more democratic model of participatory politics but which still depended on the politics of spectatorship, of reciprocity, and of classical modes of representation and intelligibility; Butler opens the scope even more to include precarious bodies who must dissent even in the face of doom. But the right to dissent has been guaranteed by constitutional republics in the US, in Chile, and abroad: how has the scene changed with the increase of policing and state violence? In the face of multitudinous manifestations, former governor Rosselló defied hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans and stayed in his seat of power, la Fortaleza, refusing to leave, reaffirming his seat and the space of power; Chilean president Piñera released los carabineros, specially-trained military outfits, who terrorize public spaces (like plaza Italia) and shoot at, detain, blind, torture, and disappear bodies in their attempts at quelling public fury. What happens when these bodies refuse to disperse, when they aim to reclaim privatized space as theirs, when they rename these spaces in their favor to reverse power roles? What’s in a name?

After weeks of protests, both spaces were renamed in the wake of the demonstrations: the street where protesters overran la Fortaleza was renamed calle de la Resistencia; similarly, plaza Italia was renamed plaza de la Dignidad. These are not random names, unlike state practices of naming schools or public works in the name of an illustrious personality chosen by bureaucrats: these are concrete manifestations of public dissent, they are the chorus set in stone, they reconfigure spaces to reflect popular action and not state oppression. They inaugurate what I call spaces of resistance.

As opposed to the Arendtian space of appearance in which one body is made intelligible in the presence of other bodies, spaces of resistance are always confrontations between the neoliberal state and collective insurgencies as purported by Benjamin Arditi (2013). It reflects an agonistic space (following Mouffe 2013) in which incommensurable discourses are forced to confront each other, in which new alliances are formed and old power structures are challenged. By changing a name, this space becomes collective and is wrested from private interests: this is reiterated by the fact that online, the space comes to reflect this change, and for a while, Google Maps changed the name to the insurgent’s whim. This inaugurates new spaces of resistance to appear through the digital realm, and also inaugurates a new time in which this space, forevermore, will be known to the public not as the seat of state or colonial power, but as the place of birth of a movement in the face of destruction and precarity.

Arditi sees insurgencies as political performativities, which do not stray too far from spactacles. Insurgencies are future-building by bringing about change itself, by snowballing and viralizing, by growing so large and insurmountable that they topple the whole structure because deep down, in neoliberal times, populations are concluding that the problem isn’t just systemic: the problem is the system itself. Arditi echoes Austin when he defines political performatives as “actions and statements that anticipate something to come as participants begin to experience—as they begin to live—what they are fighting for while they fight for it”. It is a space inaugurated as it is transited: caminante no hay camino, el camino se hace al andar. Arditi also notes an interesting conception of spectatorship in the face of insurgencies: users of social media amplify them, “giving rise to a spect-actor”, a subject who participates in the inauguration of a new space with every like and share. They act to multiply the space of resistance in ways differently than simple spectators documenting: they are also holding the state accountable for misdeeds as they join the joy or dread of open rebellion.

What is at stake, then, is ownership of physical space, and how through the digital, ownership of spaces becomes more porous in the face of neoliberal policies that limit and criminalize protests. When governments attempt to co-opt public space through privatization and regulate these spaces by deregulating markets, the public attempts to take back control of the space through the physical insurgency and the digital. This is an attempt at making permanent the manifestation of an ephemeral insurgency, the trace of a resistance to the spectacle from the very space that produces the spectacle itself, inscribing also in its formation and naming the conditions of precarity that sparked the insurgency in the first place.

Both Chileans and Puerto Ricans could solidify their spaces of resistance through Google Maps. The strategy for renaming the space quickly viralized: it was as simple as opening the page or application, selecting the address, and reporting a problem, which prompts users to suggest a change. From within the framework of consumption, a way for change is possible through crowdsourcing: there is a political problem for which digital users suggest a change. This change was reflected for days at a time. They were changed back in the following days, but just like protestors who commit acts of public destruction like flipping cars, tearing down statues of colonial authorities, express their anger or goals on the walls and the streets, this is a way of transiting space in a way that shifts power relations, taking back control through any means necessary, both physical and digital. This new space, viral in nature, mythically recursive, sparks new spaces of resistance: because contemporary insurgencies aren’t programmatic in nature, that is, don’t necessarily initiate revolts with mainstream policy changes, then this space of resistance is not predetermined by the nature of the space itself: it is forever a possible space, a potentiality, a mirage on the map, a solid memory.

What interests me about the space of resistance is that it is more than a space of appearance: it is a space that populations—after the insurgency—can always come back to through the digital. Therefore, it is constantly reworked, reiterated, erased, and resurrected. It is more than simply taking back ownership of a space: it deletes the idea of ownership because the space is recollectivized. This space of resistance inaugurates a new futurity: it is the formulation of a new direction for the state, the nation/s, and the populations that transit both. This also represents a violent break from neoliberalism: by renaming, they perform this new epoch through the name itself: dignity, resistance. These are the ideals that move populations to furor, this is the performative that insurgent populations bring to the fore, and in its renaming, it becomes a new space, the first of many.

When Arditi claims that insurgencies and movements “don’t simply disappear after their work is done”, this is also true of the space in which a collective voice has been found. Just like we remember a moment of break with the past—May 1968, a localizable time in space—we can remember a space for its capacity for resistance and dignity, the birth of change. Intercepted by social media, this new name spreads like wildfire in the Internet, facilitating the conversion of spectators to spectactors: social media users can intervene in the definitions of the space itself even if they are not within the confines of the space at all. By reappropriating neoliberal consumption practices for political change, the easiest, most immediate method for producing change, then insurgencies leave a more lasting mark on the space and time that they perform simply by changing a name and reversing the political spectacle.

Espectáculos Fujimoristas: Televised Control and Dehumanization in 1990s Peru

It is almost impossible to consider the dimensions of political spectacle in recent years without accounting for the role of the camera and of other technologies that allow for the mass (and often close to immediate) dissemination of audiovisual information. The physical and ideological formations that support this expanded circulation serve many functions but should be understood to organize the public sphere and what Rancière might term “common sense”, along central nodes of hypervisibility. Since their technological inception, live television broadcasts have historically been used by political figures to reach their constituents, often bypassing institutional or more formals channels for communication. The visual intervention of the television receiver within the domestic space, beaming carefully curated images to living rooms across a country, develops a new intimacy with political messages and figures. For populist leaders capable of manipulating affect through the monopolization of the gaze, the television has historically been an indispensable tool.

Despite the seemingly deterritorialized status of many communication mechanisms, these technologies are anchored in key geographical locations and infrastructure. The ‘spaces’ of these mediated events can then fall into three distinct categories: 1. the space of the mediatic event itself – this may be identified as the point at which cameras (often several) are directed for broadcast; 2. the space(s) of transference, including the fiber optic cables, or radio waves, that transfer the information from and to the receivers; and 3. the (domestic) space of the television receiver, related to particular forms spectatorship and the affective ordering produced by the televised spectacle. Each of these ‘sites’ become an integral part of contemporary politics; the curation of the first two, in particular, at the hands of powerful political figures, can narratively be deployed to ‘legitimate’ undemocratic forms of governance.

The examination of these cases as examples of televised spectacle in particular points us to a key reflection of the Critical Art Ensemble, the potential condition of modern power as nomadic (Lane and Dominguez, 134), not as permanently held in immobile institutional entities but as constantly travelling through mediated structures, and fundamentally reliant on them. The capacity to manipulate the circulation of images can displace established forces of legitimation and narratively be used to justify violence and dehumanization. Significantly, the television does not operate under the same logic as cyberspace – it is not organized around decentralized or distributed network structures and does not develop the same participatory formations. While this analysis of television spectacle might appear anachronistic, it is crucial that we consider the non-linear processes of technological adoption. It is not that the Internet and networked communication perfectly replaces “older” mediatic structures, rather they co-exist, developing overlapping spatio-temporal formations that necessarily challenge teleological narratives. Even though I examine past events, these still provide insight into structures of power and forms of relating to technology that persist.

In this brief examination of televised political spectacle, I consider the historical case of Peru between 1990 and 2000, a period of heightened political violence usually narrated as taking place between two armed Marxist revolutionary groups (so-called “terrorist groups”) and the State, during the presidency of Alberto Fujimori. At this time, the televised space (curated by State representatives and very often directly by Fujimori) grew increasingly tolerant of extreme violence. The images reflect a new visual protocol working to affirm the absolute dehumanization of the “terrorist” and the “terrorist” body. The presence of the cameras in the events considered here is absolutely intentional – it reveals the control Fujimori held over the press, the ways in which he manipulated its constant craving for sensationalized content as well as the magnetism of visual spectacle. Even though these events are now understood by many as examples of extrajudicial violence, emblematic of a government responsible for gross human rights violations, the curation of these images attempts to deliver an alternative narrative. The assertion of supposedly legitimate power attempts to transcend the brutality pictured; the narratives constructed around the images, and which literally frame them, seek to direct our gaze and to mold our affective response. By understanding these images as both testimony and proof, as Rancière might suggest, and by reading the images with a sense of responsibility (to democratic ideals and to the preservation of human dignity) as encouraged by Ariella Azoulay, we might be able to challenge violent narratives with the evidence of spectacle itself. Ultimately, I hope the following examples can show the distortions of time and space that are produced by the deliberate government manipulation of the camera lens and the television screen; and how these events transform the sites they implicate.

1.On April 5, 1992, President Alberto Fujimori staged what would later be known as his autogolpe or “self-coup”. He appeared on national television and argued that, given the circumstances of corruption in Congress and the Justice Department and the need for drastic socio-economic policy reform, he felt “responsible to take exceptional measures”. He had decided to “temporarily” dissolve Congress and completely reorganize the judicial branch – essentially centralizing political power in the office of the presidency. The announcement, shown in the photograph above framed by the edges of a CRT television set (as it is often reproduced and remembered photographically) can help understand the role of the media in shaping the dynamics of power between the two competing armed groups (the “terrorist” organizations and the state), and deconstruct the primary access-point for many Peruvians to the imminent terror they were enlisted to fear and detest.

This particular visual framing already displaces established codes for the consumption of political messages and develops a new image of state power. The absence of traditional symbols of institutional power, like a podium or a recognizable government building in the background, and the intimacy of a single-camera set-up (definitively opposed to a press conference environment, for example) eliminates the sense of formal mediation between the president and the Peruvian public. Fujimori looks directly at the camera, as though having a conversation with people in their homes, and justifies his takeover of total political power to the people themselves –those who had followed the unfolding narrative on TV already– and not to an established symbolic order. It visually establishes a new order of governance, one that Fujimori had previously applied during his campaign but which gains new relevance given the particular claim to power here enacted.

The curation of this particular televised spectacle, which focused national attention on a medium close-up of the president, should also be understood to conceal or redirect attention from other (violent) actions, as spectacles often do, producing simultaneous areas of relative invisibility. It should also be understood as the first of a series of subsequent televised spectacles, as spectacle often functions as an action or “beginning” in the sense of Arendt. Among the hidden covert operations associated with this particular spectacle were the kidnappings of journalists like Gustavo Gorriti and of political opponents like Jorge del Castillo by the military intelligence services, which occurred on the same day. The subsequent spectacles include the military tanks which situated themselves outside the Congress building and outside the courts. The photographs included in the gallery above also show the public dissent, as well as support, produced in response to the measure. Fujimori’s televised address, despite its concrete intentions, was distinctly interpreted by different groups — the spectacle does not uniformly capture or control the ideological formations of the public, it operates as action, powerful action but never fabrication.

2. It is hard to think of a clearer example of political spectacle than the televised presentation of Abimael Guzmán, the ideological leader of the Shining Path, on September 24, 1992. Guzmán had been captured by the National Counter-Terrorism Directorate (DIRCOTE) almost two weeks earlier alongside other high-ranking members of the Shining Path. For several days, the press had been expectantly waiting for the presentation of the captured leader; they quickly gathered in an outdoor portion of the DIRCOTE offices as soon as the announcement was made. A black metal cage had been unusually set-up in the corner of what seems to be a basketball or soccer court, creating an optimal angle for the photographic capture of the event. The cage was initially covered by a yellow and blue curtain which was theatrically lowered to reveal Guzmán in a striped uniform with the number 1509 printed across his chest. In interviews (like the one featured above), President Fujimori explained the reasoning behind these curated decisions: “In Peru, prisoners don’t wear striped uniforms, but, since it’s so common and often seen in movies, I thought it would be illustrative to show him behind bars to indicate that finally the Shining Path was being defeated.” The deliberate appeal to cinematic symbols shows the extensive manipulation surrounding this media spectacle and the intentions to visually narrativize control and power. It also points to the dynamics of a shared space of television. The space of the television screen exemplifies the overlapping of entertainment and politics. On the same screen one can watch variety comedy shows, Hollywood films, morning talk shows and political addresses. The borrowing of cinematic convention in the presentation of Abimael Guzmán, almost reduced to the caricature of a criminal, perfectly models the political potential (or danger) of television. The artificial construction of this space reorganizes it; the site is no longer a basketball court, or a site of recreation, but a temporary prison and a stage.

Despite Fujimori’s intentions to absolutely criminalize Guzmán through the curation of the artificial environment, a video recording of the event reveals a complex set of tensions. After his charges are read, Guzmán proceeds to give an improvised address for about fifteen minutes, preaching his Marxist-Maoist values and assuring the public that the “revolution” would live on. While he speaks, journalists are regularly heard screaming insults at him, calling him “crazy” and shouting that he “looks like a clown”. He responds by shouting back: “Some think that this is a defeat – keep dreaming! This is only a setback, that’s all!” This back and forth develops a different set of power dynamics, which transcend the intentions of the spectacle and might be read alongside Hannah Arendt’s conceptualization of action. This curated space of appearance, which appears to centralize the national gaze (or at least the gaze of the national press) and attempts to locate Guzmán within a particular fabricated narrative, ultimately fails to restrict his capacity for action. Despite the deliberate construction of the event to produce a sense of criminalization, Guzmán’s speech (and action), amplified by its mass televised mediation, can be read different from what was intended (as I am perhaps doing now) – affirming Arendt’s characterization of actions as both “boundless” and “unpredictable”. The meaning of a political spectacle as action is then necessarily constructed from a multiplicity of perspectives. Without exempting Guzmán from accountability for the consistent attacks and thousands of deaths he was responsible for, spectators can resist his representation in this particular spectacle and use the case to examine the workings of power.

3.On April 22, 1997, the image (below) of President Fujimori indifferently walking by the dead body of Néstor Cerpa was broadcast live on national television. Four months earlier, the MRTA (Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru), an armed leftist group, had seized the home of the Japanese Ambassador, Morihisa Aoki, during a gathering to celebrate Emperor Akihito’s birthday, taking more than 500 hostages. They had slowly released hostages throughout the four-month period, with 72 remaining by December 31, 1996. In a carefully planned and rehearsed mission, a special group of the Peruvian Armed Forces entered the residence on April 22, 1997 and rescued 71 of the hostages. All fourteen members of the MRTA were killed, along with two members of the Armed Forces and one hostage. Testimonies from the hostages and new autopsy reports would later reveal that many of the MRTA members were killed after having surrendered and while begging for their lives. President Fujimori arrived at the ambassador’s residence only moments after the mission had been completed; his visit was broadcast that night in national new channels. He is shown following the path the special forces travelled to secure the residence. The bodies of the killed MRTA members were not moved or covered before the filming. Some of the television broadcasts also included footage, provided by the State itself, of the preparations that the soldiers had undergone before the mission. They showed the team rehearsing the maneuvers in a facility designed to replicate the residence, and President Fujimori looking at a to-scale model of the building.

The additional “b-roll” of the operation, which was ready for distribution to the press immediately following the rescue, depicts the extent to which the operation was intended as a mediated spectacle. It was understood by Fujimori and the State that, if successful, this could be articulated as a clear “win” for their war against “terrorism” for the Peruvian public. This is also seen in the impromptu press conference that Fujimori gives following the tour of the site, while standing on top of a parked car, where he reinforces that message that the government will not tolerate the actions of terrorists nor negotiate with them. Most shockingly, however, this particular televised spectacle showcases the complete visual dehumanization of the “terrorist” body. In other circumstances, it might seem absolutely inadmissible for graphic images of piles of dead bodies (of individuals killed by the state) to be shown in national primetime TV. Yet in the narrativized context of a violent war between the “terrorists” and the State, they are interpreted more as trophy photographs, what Jay Prosser describes as “symbols of the conquest of others” (Prosser 2012, 9). The Peruvian public as spectators are then assumed to be, or forcefully positioned as, complicit with the violence and dehumanization of the MRTA members. Television spectacle can then also be an important tool to examine the mobilization of discursive conditions of “crisis” and the status of human rights in a particular space-time.

Lisístratas contemporáneas

En Lisístrata, comedia de Aristófanes (411 a.C.), las mujeres, cansadas de la presencia intermitente de sus esposos por causa de la guerra, deciden hacer una huelga de sexo con el propósito de obligarlos a firmar la paz y regresar a Atenas. Previendo que al estar en sus casas los hombres tratarán de convencerlas e incluso obligarlas a tener sexo, las mujeres abandonaron sus hogares y se reunieron en la Acrópolis, la cerraron con llave y se negaron a salir hasta que los atenienses y los acarnienses llegaran a un acuerdo. Hay en este gesto colectivo una transgresión de los órdenes políticos, sociales y familiares establecidos, además del estatuto regulador del cuerpo y del uso y distribución de los espacios públicos y privados.

La huelga de sexo o huelga de piernas cruzadas ha traspasado el campo de la ficción y la comedia para, con objetivos y en contextos muy distintos, convertirse en una herramienta política efectiva, afectiva y no violenta. Su historia incluye manifestaciones en Liberia, Colombia, Kenya, Filipinas, por nombrar algunos casos, con frecuencia en comunidades profundamente conservadoras, donde el mandato heterosexual y la organización en torno a la familia nuclear siguen siendo las bases inamovibles e incuestionables de la sociedad, también en lugares atravesados por guerras donde los cuerpos de las mujeres han sido objeto de sistemática violencia física y sexual. Más recientemente han sido convocadas de manera espontánea en espacios virtuales por activistas estadounidenses, como protesta ante el desmonte paulatino de las herramientas legales para poner fin a embarazos no deseados en el marco del derecho de las mujeres a decidir sobre sus propios cuerpos.

Paradojas espaciotemporales

La huelga de sexo da pie a lecturas contradictorias sobre la subjetividad y el mandato de género ya que puede ser vista como una herramienta política que profundiza las nociones binarias en torno a la concepción de los cuerpos y las sexualidades, mantiene la norma heterosexual intacta y reclama a los hombres un cambio en el ejercicio del poder público sin cuestionar totalmente esa asignación de género. Pese a estos problemas de alcance, también puede ser leída como un accionar subversivo en más de un sentido. Las huelgas de sexo son actos de apropiación del deseo y del cuerpo por parte de sujetos históricamente subordinados, cuya corporalidad ha sido entendida como un repositorio de fines reproductivos y de placer que suplen las necesidades sociales (mantener estable a la comunidad mediante la garantía de la natalidad) e individuales (satisfacer el placer masculino); e incluso como botín de guerra o pieza indispensable para el dominio y desarticulación de las poblaciones enemigas. En ese gesto de reapropiación, las mujeres aparecen en la esfera pública mediante sus cuerpos y hacen manifiesto su carácter político, deseante y solidario, siendo ellos un objeto mismo de la acción política.

De acuerdo con Judith Butler en Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, “what we are seeing when bodies assemble on the street, in the square, or in other public venues is the exercise—one might call it performative—of the right to appear, a bodily demand for a more livable set of lives” (2015, 31). Para las mujeres que deciden hacer protestas de piernas cruzadas, además de la reivindicación, la congregación en espacios públicos tiene un componente adicional: mantiene la discusión sobre el deseo y la abstención en el terreno de lo comunitario, puesto que al regresar a sus casas corren el riesgo de individualizar su acción en principio colectiva, volviéndola una confrontación uno a uno. Así la congregación pública tiene el efecto adicional de difuminar la frontera entre los espacios y los tiempos públicos y privados.

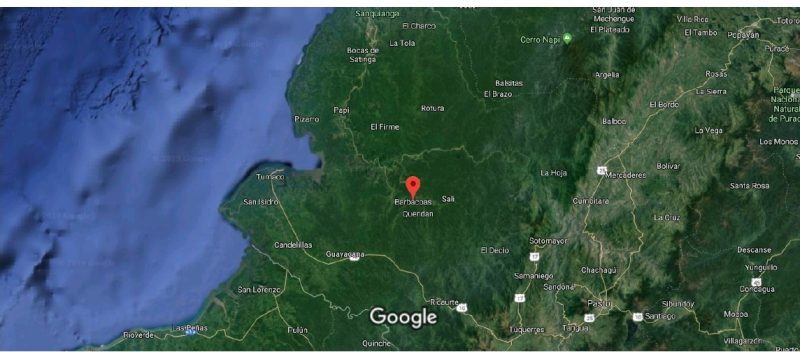

El lugar del deseo en la esfera pública

El planteamiento de una huelga de piernas cruzadas pareciera proponer un castigo a los hombres y una comprensión de su subjetividad a partir de un fuerte e incontrolable deseo sexual, esta lectura reproduce estereotipos de género nocivos con los que se suelen justificar, por ejemplo, el acoso y la violencia sexual. Sin embargo, al volver al texto de Aristófanes, vemos como la propuesta de Lisístrata es, en principio, rechazada por las mujeres, quienes se niegan a abandonar el sexo: “Ask what you like, but not that! If I had to, I’d be willing to walk through fire—sooner that than give up screwing. There’s nothing like it, dear Lysistrata” (Aristophanes 2107, 21) responde Calonice. Sus palabras, similares a lo dicho por otras de las mujeres convocadas por Lisístrata, hacen visible el deseo femenino. El sacrificio al que obligan a sus parejas es a la vez una invitación a unirse a la protesta y a un reclamo que va dirigido al Estado. Así, en Barbacoas, Colombia, luego de varios días de huelga los hombres se unieron a la manifestación y, junto con las mujeres, solicitaron a las autoridades locales y nacionales la pavimentación de la única carretera que une el municipio con el resto del país. Entender la huelga de sexo no como un sacrificio impuesto de manera mayoritaria a los hombres, sino como un esfuerzo compartido por seres y cuerpos deseantes, posiciona en la esfera pública un asunto que, con distintos matices, sigue siendo tabú en las sociedades contemporáneas: el deseo y particularmente el deseo femenino.

El deseo posicionado en el espacio público conduce a la pregunta por el lugar de las emociones en el ámbito político. Siguiendo la tesis de Rancière sobre la división de lo sensible y entendiendo esta como un “system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitation that define the respective parts and positions within it” (2004, 12), podemos preguntarnos por los espacios y los tiempos del deseo, y las formas de actividad relacionadas con él. Rancière plantea que la distribución de lo sensible involucra una delimitación de lo comunitario, lo visible e invisible, también de lo que tiene una voz o no y dónde esta puede ser activada (2004, 13). En las huelgas de piernas cruzadas, el deseo, a través de la imposibilidad de su concreción, ocupa el espacio público; hay una activación política a través de un mecanismo afectivo y pasional. Según Chantal Mouffe, la teoría política democrática sigue dos modelos: el agregativo, aquel en el que “political actors [are] being moved by the pursuit of their interests” (2013, 6); y el modelo deliberativo, en el que se destaca “the role of reason and moral considerations”(2013, 6). Para la autora, “what both of these models leave aside is the centrality of collective identities and the crucial role played by affects in their constitution” (2013, 6). Los modelos democráticos mencionados están instalados sobre el poder de la razón, son entendidos como el triunfo de esta sobre las pasiones, Mouffe cuestiona este paradigma al entender la pasión “as the driving force in the political field” (2013, 6). Esa pareciera ser la intuición de las manifestantes que acuden a las huelgas de sexo como mecanismo de acción política. Volviendo a Rancière, podríamos preguntarnos si las huelgas de sexo pueden ser entendidas como dislocaciones, al menos momentáneas, de los espacios, tiempos, formas del deseo, también de su visibilidad y su potencia política.

Ubicar en el mapa algunos de los lugares en los que las mujeres han acudido a esta forma de protesta evidencia su rol social y político subordinado pese a las diferencias culturales, sociales y religiosas entre las comunidades a las que pertenecen, desde entornos campesinos en el sur montañoso de Colombia hasta alianzas interreligiosas entre musulmanas y cristianas en Monrovia, capital de Liberia; las marcadas diferencias entre los contextos mencionados, pero la semejanza en la subordinación basada en las diferencias de género, habilita la pregunta por esta subordinación en los demás espectáculos políticos que han sido localizados en el mapa interactivo, y propone lecturas interseccionales de los mismos.

Thinking through “Cyberspacetime”

Working from Jacques Rancière’s description of what constitutes politics proper, Étienne Balibar, in his essay “Politics and the Other Scene”, argues that there is a paradox inherent in the predication of politics on “the part of no part”. The part of no part can neither be a subject in nor a subject of politics; therefore, the part of no parts’/the have-nots’ existence, which is the condition of the possibility of politics, is at the same time the condition of its impossibility. Using Rancière’s formulation as a point of departure, Balibar advances three theses: all identity is fundamentally transindividual (it is a bond validated among individual imaginations); rather than identities, we should speak of identifications (no identity is “once and for all”); and every identity is ambiguous (no individual has a singular identity). Interpreting the title of Balibar’s essay along these lines, it could be that Balibar was getting at a formulation of “politics” and the “other scene” as mutually constitutive and codependently materializing economies: the “other scene” is distinctly named apart from “politics” and simultaneously its condition(s) of emergence. These are not isolated events, strung together by narrative threads, one acting and the other reacting, endlessly. They are circulations of energies, coalescences and dissipations, cool fogs and hot, dense balls of gas. We cannot mean politics without also meaning performance; we cannot mean appearance without also meaning disappearance—what we have, then, is surplus rather than positive and negative; duality rather than binary.

This “duality” is based on the quantum-mechanical property of being regardable as both a wave and a particle, and this “framework” or “mode of perception” applied generally to the analysis of political spectacle as the metonymy or intersection of “politics and performance” can also be applied to a more specific analysis of the digital-analog spacetime of political spectacle. Using “duality” as an anti-binary framework, it is interesting to discuss politics and performance as two different measurements of the circulation of power, of the economy of affects and the sensory, of the coalescence and dissipation of bodies oriented towards desires. Likewise, it is interesting to discuss digital and analog spacetimes of political spectacle as closely entangled, deeply imbricated, and mutually affective realities. In other words, let us consider that the digital is no longer just a pervasive part of our reality, no longer a frightening specter looming behind screens, trapped. Indeed, it is our reality—or, as Mark Hansen argues in his book Bodies in Code, our reality is now best thought of as “mixed reality” (Hansen 2006). As with mixtures of other types, the ingredients—the digital and the “real”—lose what clear separation or distinction they appeared to have before: they are blended to make something new.

Jacques Rancière, in his essay titled “Politics of Aesthetics,” introduces us to his concept of “the distribution of the sensible” the system of divisions that define, among other things, what is visible and audible within a particular aesthetico-political regime. For Rancière, the essence of politics consists in the distribution of the sensible, asserting that these aesthetic regimes are simultaneously theoretical discourses—that is, sensible reconfigurations of the facts they are arguing about. The distribution of the sensible is one interesting articulation of the energy circulations and materializations of politics and performance, which demonstrates the systematic definition of divisions and boundaries, rather than its predication on ever-fixed divisions and boundaries. The essence of politics (performance) is, then, perception, which we feel as excitations of senses and affects—not isolatable phenomena, but economies, a series of practices (Balibar here, again). To move against a distributive understanding of performance (political spectacle) is to contribute to the maintenance of what Diana Taylor calls ‘percepticide’: The American Way.

This “distributive” understanding of political spectacle can be engaged with along the lines of what the Critical Arts Ensemble calls “digital aesthetics” and “recombinant theater,” allowing us to work through Hansen’s “mixed realities” in a way that gives Judith Butler’s “performative theory of assembly” the language of “hardware, software, wetware” (CAE; Hansen; Butler). Chantal Mouffe, in her essay titled “Agonistics: Thinking about the World Politically”, refers to “politics” as the ensemble of practices, discourses, and institutions that seek to establish a certain order and to organize human coexistence in conditions which are always potentially conflicting—there is a reduction of passions and a distillation of identities. This is perhaps how we must think of political spectacle generally, although we would wish the discussion here to perform a multiplicity of definitions on its own. What Mouffe wants to get across is that to predicate an articulation of political spectacle on disappearance, absence, nothingness; or, to conjecture that politics and performance (often assumed to be a regime vs. a resistance), appearance and disappearance, power and powerlessness, operate as binaries is to “eliminate the passions”, to define borders between bodies, ignoring any leakage, any transference, any bleeding. Those passions, rather, demand our orientation towards them, as an assembly, as a collective body—like digital networks; “digital aesthetics.” Along these lines, Diana Taylor, in her book, Performance, argues that “people absorb behaviors by doing, rehearsing, and performing them” (13). Performances “operate as vital acts of transfer, transmitting social knowledge, memory, and sense of identity through reiterated actions” (25). Taylor advocates for what we could refer to as “trans-spacetime” in her engagement with the digital, explaining that “the digital has become an extension of the human body”: we all have ‘data-bodies’ (108). Taylor concludes that “Experience can no longer be limited to living bodies understood as pulsing biological organisms. Embodiment, understood as the politics, awareness, and strategies of living in one’s body, can be distanced from the physical body” (138).

Working through these theories in constellation, this analysis of the spacetime of political spectacle, through its engagement with the digital, can bring in stimulating psychoanalytic concepts from Stephen Hartman’s essay “The Poetic Timestamp of Digital Erotic Objects.” In this essay, Hartman describes “cyberobjects” and “technogenesis” as constitutive elements (performances) of “screen relations” in what we will name “cyberspacetime”. Objects in cyberspacetime are “introjected” by someone—that is, one comes to identify with a cyberobject and takes it into oneself—and, as groups interact with these cyberobjects, these objects become “groupal objects”. In other words, these cyberobjects become the basis of a technogenesiswhat Mouffe would see as a mobilization of passions. In the spirit of Butler’s acknowledgement of vigils as performative assemblies, we will look at performative assemblies in cyberspacetime, which mobilized affects and passions towards a democratic design (specifically, mutual support and interdependence), organized around the cyberobject of the hashtag, and developing into movements that dissolved any perceived boundaries between the spacetimes of the digital and the analog/real, in order to re-conceptualize and expand our discussion of the spacetime of political spectacle.

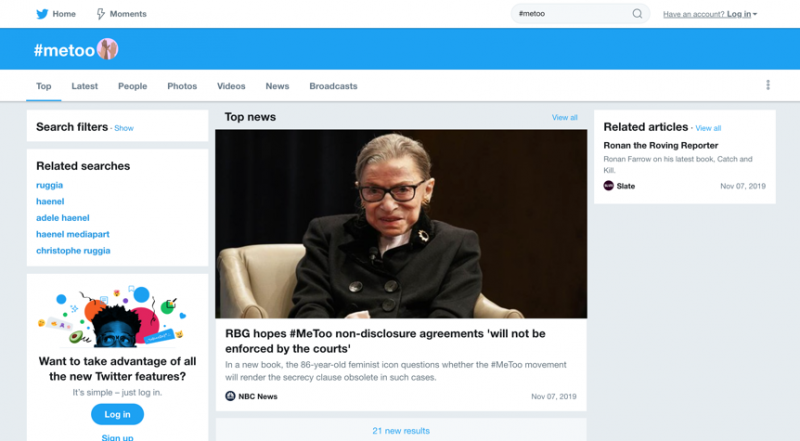

#MeToo

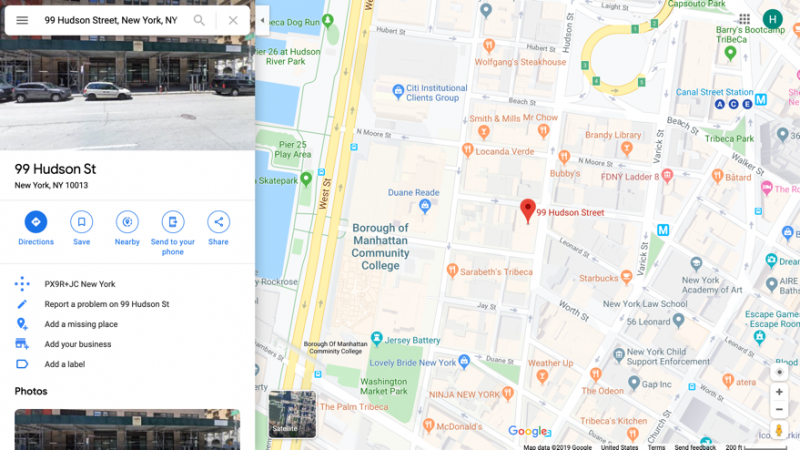

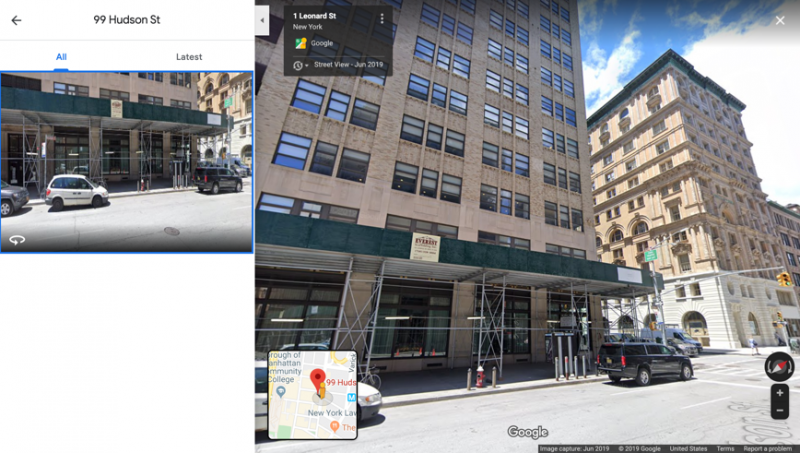

Sexual assault survivor and activist Tanara Burke created the #MeToo movement on the social media platform Myspace in 2006, inaugurating a social movement against sexual assault and sexual harassment that has come to span multiple continents. Burke began with the intention of empowering women through a distribution of the sensible, focusing on constructing a community of empathy and strength in numbers by demonstrating visibly how many women have survived sexual assault and harassment. Like other social movements with similar tactics, the #MeToo movement was/is based on breaking silence and making visible the massive community that has been strategically concealed from public attention. A search of the hashtag #MeToo on Twitter, the social media platform where the hashtag is (at the moment) most widely engaged with, shows the movement of the hashtag today (Figure 1). This feature of social movements that were born in the digital and grew in “mixed reality” is an immensely significant feature of our lives as political actors today. We witness and engage with the development of the movement in “real-time” through its various transitions and manifestations in “real” public spaces. We work in modes through which we can organize and distribute information and media quickly. We are able to engage political moments as “spect-actors” rather than only spectators. The #MeToo movement provides an example of one such movement in this digital space which has garnered support and traction that it otherwise might not have because of the mobilizing and organizing potentials of social media. Above are google maps screenshots of what was the headquarters of the Weinstein Company (Figure 2; Figure 3). Following the widespread sexual-abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein in early October 2017, the hashtag #MeToo began to spread virally on various social media platforms. After the Weinstein accusations were circulated throughout these sources, the #MeToo movement took a firm grasp of a multitude of professional realms and institutions. Some of these include US media and fashion industries, churches, education, finance, politics and government, sports, medicine, music, journalism, military, pornography, and even astronomy, where the movement gained footing through the hashtag #astroSH (Figure 4).

Figure 1: A screenshot of a Twitter search of the hashtag #MeToo

Figure 2: A screenshot of the former location of the Weinstein Company form Google Maps.

Figure 3: A screenshot of the Google Street View of the former location of the Weinstein Company.

Figure 4: #MeToo march in the Hollywood section of LA, led by Tanara Burke.

#BlackLivesMatter

Black Lives Matter (BLM) is an international movement that campaigns against violence and systemic anti-Black racism. The movement organizes in response to and in an effort to prevent further police brutality and issues such as racial profiling and racial inequality in the United States criminal justice system. The movement began with the use of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter in 2013 on social media platforms after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin in February 2012. The movement gained national recognition for its street demonstrations following the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown, resulting in protests in Ferguson, Missoruri, and Eric Garner in New York City. In the summer of 2015, Black Lives Matter activists became a considerable presence in the 2016 United States presidential election. The originators of the hashtag, Alicia Garza, Patrice Cullors, and Opal Tometi, expanded their project into a national network of over 30 local chapters between 2014 and 2016. Garza, Cullors, and Tometi met through “Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity” (BOLD), a national organization that trains community organizers, and used there training and social media knowledge to question how they were going to respond to the devaluation of Black lives after Zimmerman’s acquittal. Garza wrote a Facebook post titled “A Love Note to Black People” in which she said: “Our Lives Matter, Black Lives Matter”. Cullors replied: “#BlackLivesMatter”. Tometi then added her support, and Black Lives Matter was born as an online campaign (Figure 5). In August 2014, BLM members organized their first national protest in the form of a “Black Lives Matter Freedom Ride” to Ferguson, Missouri after the shooting of Michael Brown (Figure 6). The activities in the streets of Ferguson caught the attention of a number of Palestinians who tweeted advice on how to deal with tear gas. This connection helped bring to BLM activists’ attention the ties between Israeli armed forces and police in the United States, and later influenced the Israel section of the platform of the Movement for Black Lives, released in 2016. The #BlackLivesMatter hashtag is a profound example of not only cross-platform (digital-analog) movement but also international solidarity.

Figure 5: A Screenshot of Ferguson, Missouri in Google Maps.

Figure 6: A screenshot of a Twitter search of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter.

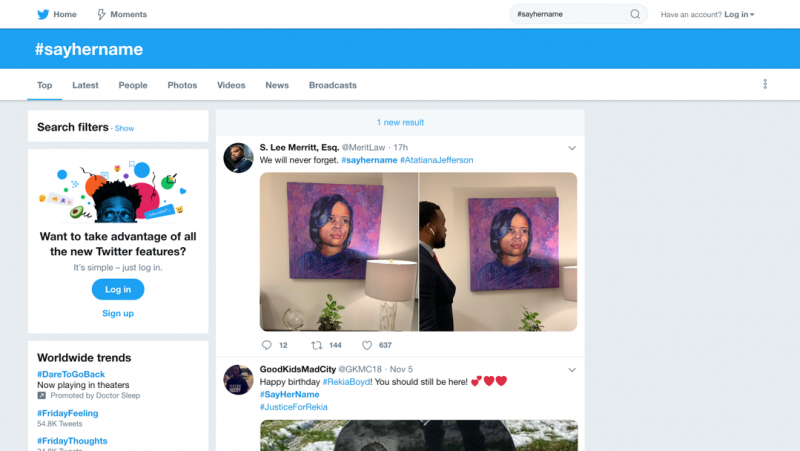

#SayHerName

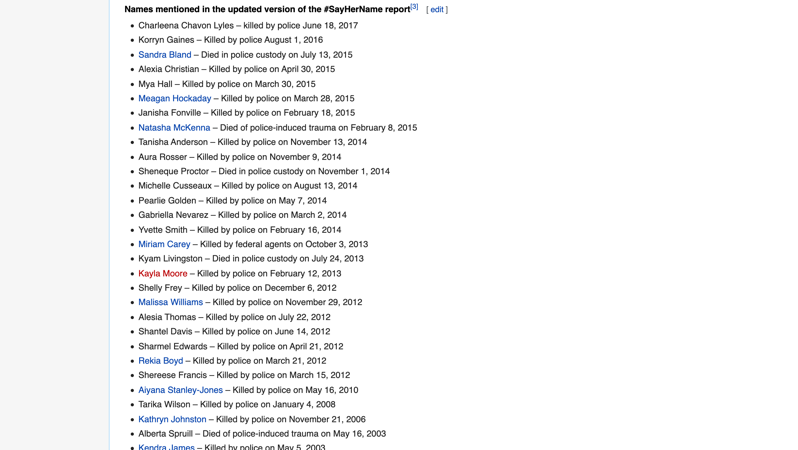

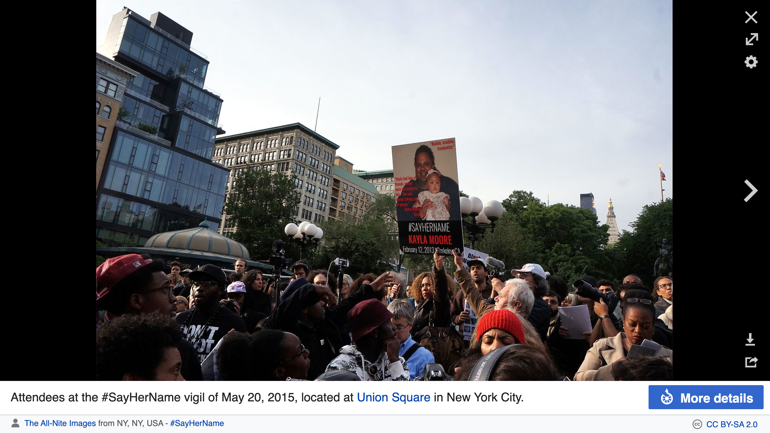

The social movement #SayHerName seeks to raise awareness for Black women who have been victims of police brutality and anti-Black violence in the United States. The movement aims to transform the public perception that victims of police brutality and anti-Black violence are predominantly “male” by highlighting the gender-specific ways in which Black women are disproportionately affected by fatal acts of racial injustice. In an effort to create a large social media presence alongside existing racial justice campaigns, such as #BlackLivesMatter and #BlackGirlsMatter, the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) coined the hashtag #SayHerName in February 2015 (AAPF). In May 2015, the AAPF released a report entitled “Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality against Black Women”, which outlined the goals and objectives of the #SayHerName movement (AAPF) (Figure 7). The #SayHerName movement additionally strives to address the “invisibilization” of Black women within mainstream media and, more specifically, the #BlackLivesMatter movement. One of the movement’s agendas is to commemorate the women who have lost their lives due to police brutality and anti-Black violence (Crum and Dvalidze). It is important here to recall Stephen Hartman’s analysis of ‘cybermourning’ in conjunction with Judith Butler’s ‘performative theory of assembly’. This cybermourning manifested also on the streets, as on May 20, 2015, in New York City, where the AAPF, along with twenty local sponsors and the Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy at Columbia Law School, organized a vigil, where many gathered to make visible Black women’s struggles against gendered, racialized violence (Workneh) (Figure 8). A screenshot of a Twitter search of the hashtag #SayHerName demonstrates the continuation of this campaign of what Keisha Edwards Tassie and Sonja M. Brown Givens call “hashtag activism” and “digital activism” in their book entitled Women of Color and Social Media Multitasking: Blogs, timelines, Feeds, and Community (Tassie and Givens 2015). The hashtag, like others, provides a digital community for activists, scholars, news reporters, and social media users to participate in the conversation on racial justice along with other social movements (Figure 9).

Figure 7: Screenshot from Wikipedia of names mentioned in the #SayHerName Report.

Figure 8: A Screenshot of the #SayHerName vigil in Union Square, New York City, 2015.

Figure 9: A screenshot of a Twitter search of the hashtag #SayHerName.

Cyberspace in Terror

For Ranciere, “politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and possibilities of time” (Ranciere 2004, 13). The entrance of surveillance technologies into the infrastructure of daily life affects each part of this statement since those moving under street cameras are always seen but muted and always stay in cyberspace/time even when they leave the physical place. However, the mere fact of being under 24-hour monitoring by street cameras does not automatically transform one into a political participant. Surveillance becomes a political spectacle when it shifts the distribution of the sensible that “reveals who can have a share in what is common to the community based on what they do and on the time and space in which this activity is performed” (Ranciere 2004, 12). In other words, when it is used to regulate who gets to perform as a community member, and how and where it must happen. Chinese surveillance systems succeeded in excluding Muslim citizens from the rest of society by tracking and putting them in detention centers. As a result, over a million people lost their ability to appear in space and control their own time. That is the case when an object introduced for safety involuntarily changes people into political actors. In this paper, I will discuss the transformation of political spectacle under surveillance and the Internet acknowledging the terror against Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in China.

Like many other digital advancements, surveillance cameras came from the military field. Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) or street cameras were first used to monitor the launch of V2 rockets in Germany in 1942, then for nuclear bomb testing in the US and, 20 years later, they appeared in public spaces (Delgado 2013). Chinese surveillance technology is nowadays the most effective in tracking bodies. It is banned in many western countries including the US while being used extensively to regulate the movement and the performance of its citizens. Since 2014, the Chinese government has been practicing brutal surveillance on its Uygur, Kazakh, Uzbek and other Muslim citizens under the anti-terroristic campaign in the Xinjiang region (Buckley and Mozur 2019). The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the largest Chinese province, has been under the governmental spotlight long before massive digital tracking due to Uighur citizens’ self-identification, and their religious and political views not favored by the communist government.

The communist party has been expanding technological surveillance in the region to detect actions and opinions that are controversial for its ideology. Foucault views it as “the emergence of techniques of power that were essentially centered on the body, on the individual body” “their separation, their alignment, their serialization, and their surveillance” (Foucault 1975-76, 242). The tracking of Muslim bodies is what Foucault calls biopower since Chinese sovereignty is expressed through the regulation of “making” live and “letting” die specific portions of its society (Foucault 1975-76, 241). Cameras in every district, checkpoints, tracking mobile applications are used to make minorities visible within every space all the time. The staged digital infrastructure puts Muslim citizens under the spotlight of the Chinese Communist party’s political spectacle without any consent to perform in it. It later transformed into a physical disappearance of over 1 million Muslims in concentration camps. So the body in a physical space became an entrance point for exerting digital power, while the information created in the digital space led to the regulation of the physical body.

To follow this process, let’s “walk” through a day in Kashgar, one of the major cities in Xinjian. As a Chinese Muslim citizen, you are forced to have a phone with an installed governmental application that is connected to your national ID and your digital body (Zhong 2019). That body has no limits. It extends with every activity you make on your device: the messages you send, the websites you visit, the photos you take and keep. You haven’t texted to your relatives abroad in years, neither read Koran verses nor take family pictures since all of it can lead to an immediate detention. You leave your house to go to the local bazaar. Walking on the streets where your community lived for centuries you must pass checkpoints every 200 meters through face recognition systems. Here you are in a line at the entrance to the bazaar. Each crossing goes directly to the C.E.T.C. platform with a database of 68 billion records on a population of 720 000 and contains information about every movement and activity done in real life or virtual (Cockerell 2019). And while your physical body might be busy, motionless or asleep, your digital body is always moving in cyberspace. It is analyzed, scanned, compared with the whole digital community, tracking what is wrong or might get wrong with the ideological view of your physical self. So the movement of your physical body is choreographed by not only technologies themselves but the terror that the digital creates.

The government is creating a space of hypervisibility for Muslim citizens but, undoubtedly, it is not a space of appearance. For Arendt, the space of appearance is “where [one] appears to others as others appear to [them], where men exist not merely like other living or inanimate things but make their appearance explicitly” (Arendt 1998, 199). In the case of severe Chinese surveillance, Uighurs a priori appear before the government as criminals while they have no access to speak to or act upon the officials. The mechanism of detection leaves Muslim citizens muted and unmovable even though they are constantly watched and overheard. Arendt claims that “to be deprived of [a space of appearance] means to be deprived of reality, which, humanly and politically speaking, is the same as appearance”(Arendt 1998, 199). And it gets even worse when the minorities are moved from hypervisible streets to invisible camps since they are not only deprived of reality but are also removed from it.

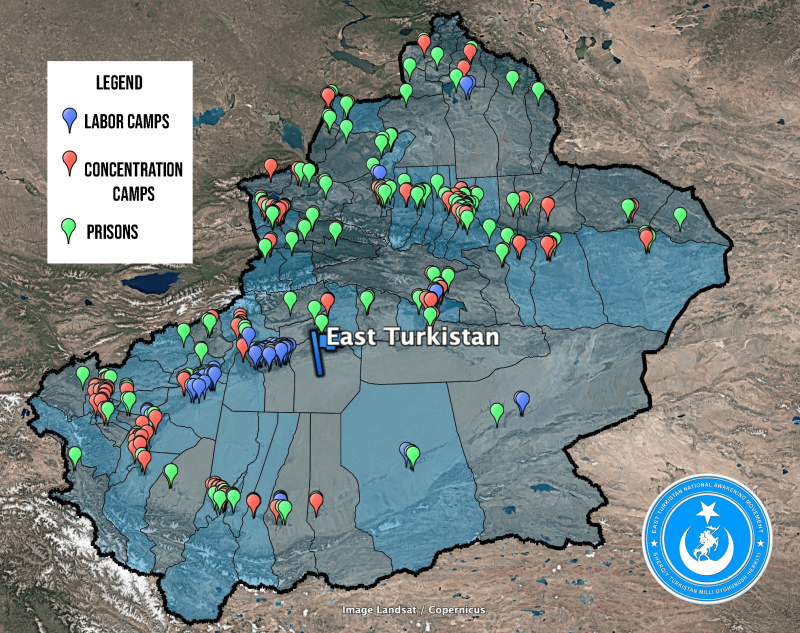

Those places are not in global services like Google maps: there are very limited photos of them since the physical access to those areas is prohibited. Therefore, satellite pictures and their analyses are what allows us to perceive their scale. Reuters’s recent investigation states that there are at least 80 detention facilities with common fenced architecture and watchtowers at every corner (Wen and Auyezov 2018). They are not the only ones trying to count and register the camps through changes in satellite images with new facilities constructed every year. In this project, I have marked only one out of many camps because it is important to navigate people to the central source of information about these virtual locations. East Turkistan National Awakening Movement (ETNAM) has identified 182 suspected Concentration Camps, 209 prisons, and 74 Bingtuan labor camps and put them together into one dataset (East Turkistan National movement, n.d). The act of mapping the camps at least make political and humanitarian violence visible. So I invite you to the cyberspace where terror against Chinese Muslim minorities is gathered into the site https://nationalawakening.org/coordinates/.

The map does not make give people detained in camps free but acknowledges the fact of their existence at least in those spaces. The Chinese government calls them “re-educational” camps while the UN and the rest of the world agrees on their function as concentration facilities. So it is important to name the locations by their true function. The activist movements call the region “East Turkistan” after its historical Uighur naming instead of the Xinjian province that was assigned by the Chinese government. Further, I will refer to the Uighur homeland as East Turkistan.

Within the regulations of the Chinese government, public protests against Muslim prosecution can be lethal for both participants and their detained relatives as it was claimed in the state documents sent to families when their members disappear. Therefore, physical assemblies for the case are created outside of the state like repetitive protests in Brussels by Uighur Human Rights Project and World Uighur Congress (Uyghur Human Rights Project 2018). Butler claims that “no human can be human alone; and no human can be human without acting in concert with others and on conditions of equality”(Butler 2015, 77). Marching for those who cannot physically attend the action is another reminder of the conditioning of human being on interaction with others even though the absence. A space of appearance for Butler is created “between” the bodies since one “does not act alone when acts politically”(Butler 2015, 77). Although detainees are invisible in the spaces of protest, I believe they appear as a bond between those who support them. So the suffering faces of Muslims can be seen not only on the surveillance cameras of the Chinese government but also on the bleeding masks with the flag of East Turkistan that the protesters chose as a recognition of the missed people.

In wrestling that power, a new space is created, a new “between” of bodies, as it were, that lays claim to existing space through the action of a new alliance, and those bodies are seized and animated by those existing spaces in the very acts by which they reclaim and resignify their meanings

Butler 2015, 85

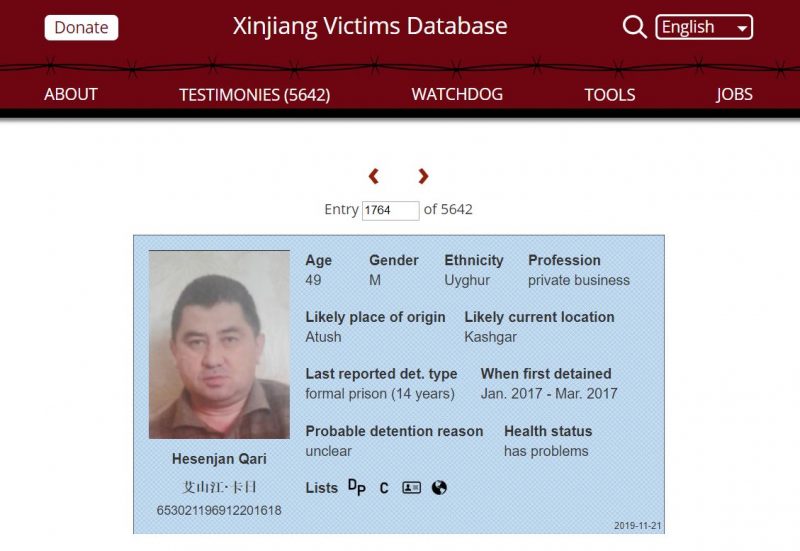

Having no chance to intervene in existing physical spaces in East Turkistan the activists reclaim the cyberspace presence of detainees. The digital archive of missing Uighurs, Kazakhs, and other minorities visually imitates the dossier created through the surveillance technology. This disidentified performance of the digital body resignifies the story of the imprisoned humans since now they have a representation that does not target them as criminals. On the website https://shahit.biz/eng/, volunteers collect fragmented testimonies from those who abruptly lost their contact with friends and family in East Turkistan (Xinjiang Victims Database, n.d.). The information gets updated hourly in interaction between people all over the world who create a digital space of appearance for the unseen physical bodies.

Pictures from presentations by the China Electronics Technology Corporation at recent industry shows. Credit: Paul Mozur/ The New York Times

Xinjiang Victims Database Website. Credit: Shahit.biz

Uighurs in China also intervene the cyberspace with the digital bodies of the detainees but within a Chinese mobile application Tik Tok (Ma 2019). The video social media app allows us to create entertaining visual content and is popular within China and abroad. Amongst funny videos, one can stumble upon silent recordings of Uighurs with an image of their detained relatives on the background. With those videos, Muslim citizens in East Turkistan do not only commemorate their imprisoned people but also send an important message that even in a position where they have no voice and representation, they choose to be political actors themselves. They reclaim power over own image and visibility by using it in their muted protest that does not need words to be understood. Even in a position of extreme physical oppression, the digital tools allow people to take own role in the political spectacle rather than act within the assigned one. The nowadays reality of East Turkistan shows that cyberspace can amplify the power of different political actors and digital bodies. One thing to remember is that this digital source of hope and fear will always have physical consequences on real humans.

“No / yo no quiero una vida mejor / yo quiero una vida nueva”

Pienso en la palabra “espacio” en el sentido en que la piensa Michel De Certeau en su libro La invención de lo cotidiano, en donde el autor distingue al “espacio” del “lugar”. El lugar se define como “un orden según el cual los elementos se distribuyen en relaciones de coexistencia” (1996, 129), relaciones que se ven determinadas por la estabilidad; mientras que “hay espacio en cuanto se toman en consideración los vectores de dirección, las cantidades de velocidad y la variable del tiempo. El espacio es un cruzamiento de movilidades” (129). Para pensar ‘espacio-tiempo’ resulta muy útil adoptar la visión que tiene De Certeau, pues la idea de un espacio móvil y no fijo nos permite leer esta selección de coordenadas en nuestro mapa como espacios atravesados por la dimensión temporal, de entrecruzamientos, de movimiento y de transformación.

Así, resaltar, dar a luz o visibilizar esta selección de puntos en este mapa funciona como uno de los modos para posicionar al migrante como un sujeto político emancipado capaz de resistir un momento de la historia en el que, desde el marco de las instituciones, se le da continuamente la espalda. Es el migrante que, junto con otros migrantes en comunidad y en nuevos lazos de solidaridad, alza su voz y resiste: aquí estamos, aquí seguimos avanzando, nosotros existimos, estamos organizados y queremos una nueva vida.

Si pensamos en la categoría de ‘ciudadano’ en relación al migrante, vemos como es un concepto que en muchos de los estados-naciones contemporáneos es una categoría brutalmente desterrada. En el ideal político que mencionaba Balibar: “To be a citizen, it is sufficient simply to be a human being” (2002, 4) el migrante, completamente deshumanizado, quiebra los principios de base sobre los cuales,en teoría, se sostienen las sociedades modernas y que desarrollaré a continuación.

En mi selección, y desde la perspectiva del poder autoritario y deshumanizante, elegí la visualización de dos espacios: un centro de detención de ICE que opera en Brooklyn y los prototipos del muro que el presidente Donald Trump ordenó a construir en la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos. En el primer caso, tenemos al Brooklyn Metropolitan Detention Center, ubicado en 80 29th St, Brooklyn, NY 11232. Elegí darle visibilidad a este lugar dada la proximidad que tiene con nuestro entorno y las circunstancias en las que probablemente como transeúntes hemos pasado por esa calle y jamás nos imaginamos lo que puede suceder adentro del recinto. En la actualidad, no resulta muy alejada la idea de pensar los centros de detención de ICE como nuevos campos de concentración. Esto resuena con las idea de Agamben sobre el campo y su conexión con el trabajo de Hannah Arendt al respecto: “The paradox from which Arendt departs is that the very figure who should have embodied the rights of man par excellence –the refugee– signals instead the concept’s radical crisis” (Agamben 1998, 126). El migrante detenido en estos centros, al encontrarse en una especie de limbo en el que no puede ser reconocido como ‘ciudadano’ de un estado-nación, pierde cualquier tipo de protección, su vida queda a la intemperie de algún sistema jurídico-político y de sus derechos. Entonces, cada uno de estos centros de detención de ICE quedan enmarcados bajo el estado de excepción, ese espacio en el que, como su nombre lo indica, debería ser una excepción, pero se convierte en la regla: “The constitutive nexus between the state of exception and the concentration camp: The camp is the space that is opened when the state of exception begins to become the rule. In the camp, the state of exception, which was essentially a temporary suspension of the rule of law on the basis of a factual state of danger, is now given a permanent spatial arrangement, which as such nevertheless remains outside the normal order” (169).

Los ocho prototipos de muro instalados por la administración de Trump en 2017 ahora se pueden visibilizar en Google Maps como si se tratara de una ‘atracción turística’. Cuando Trump visitó este espacio, en marzo de 2018, señaló:

But the border wall is truly our first line of defense, and it’s probably, if you think about it, our first and last, other than the great ICE agents and other people — moving people out. (…) So this was really a day where we look at the different prototypes of the wall. You’ve seen them. The media has seen them. And some work very well; some don’t work so well. When we build, we want to build the right thing.

White House, 2018

Este espacio incluso cuenta con reseñas de visitantes evidenciando un fuerte racismo que elegimos denunciar y problematizar al resaltarlo en nuestro mapa. Algunos de los comentarios problemáticos de este espacio fronterizo se pueden leer en la plataforma Google Maps: “Nothing like eating a taco and washing it down with an ice cold Coca Cola made in Mexico while watching the Mexican Pole Vaulting team try-outs trying to get over the wall. Excellent”. También, “Hope the mexicans won’t dig under it…”

Lejos de ver al migrante como un sujeto pasivo, es importante desde mi visión, posicionarlo como un sujeto organizado, que se moviliza acompañado, y que a través de distintas instancias comunitarias es capaz de resistir y avanzar. Desde la mirada de Foucault, se entiende al migrante como el sujeto inversor de sí mismo y a su desplazamiento como un costo en función del cálculo de dicha inversión: “migration is an investment; the migrant is an investor. He is an entrepreneur of himself who incurs expenses by investing to obtain some kind of improvement” (2009, 230.) En ese sentido me interesa insistir en quitarle de encima una carga de pasividad al sujeto que migra. Para mostrar algunos lugares de resistencia elegí visibilizar un centro comunitario en Woodside, Queens, en el que todos los viernes a las 6:00 p.m. se reúne un grupo de migrantes LGBTQ, en busca de ayuda, apoyo y solidaridad. El grupo está coordinado por Lorena Borjas, una activista trans mexicana de 60 años que lleva ya veinte años en Nueva York y que se ha convertido en apoyo fundamental de muchas personas trans que vienen a Nueva York en busca de una nueva vida. En el grupo se realizan diferentes actividades, desde charlar con abogados, coordinar actividades para reunir fondos, hasta compartir testimonios que de alguna manera ayudan a transmitir esperanza entre quienes aún no tienen una situación definida en la ciudad.

Si buscamos que los espectadores se incomoden, se movilicen, esto me hizo pensar en la ayuda y la acción que puede venir desde el lugar del privilegio. Por eso, destaqué en el mapa a la librería McNally Jackson ubicada en uno de los barrios más privilegiados de Nueva York: SoHo. Desde allí, el uruguayo Javier Molea, director de la sección de español de la librería, también coordina la iniciativa Fondo Solidario para el Inmigrante. Este fondo, como declara en su página oficial: