Table of Contents

Introduction

Unveiling Sovereignty

Political Strategies & Conventions

I. The Technology of Scapegoating, An Owner’s Manual

II. Weaponizing Theatre

III. The Gift

Epilogue

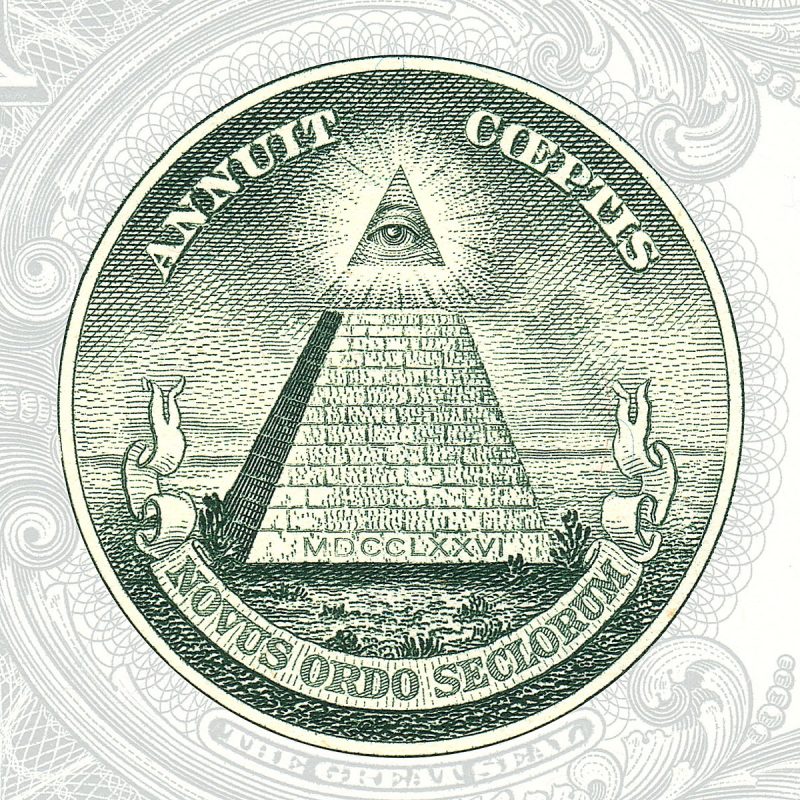

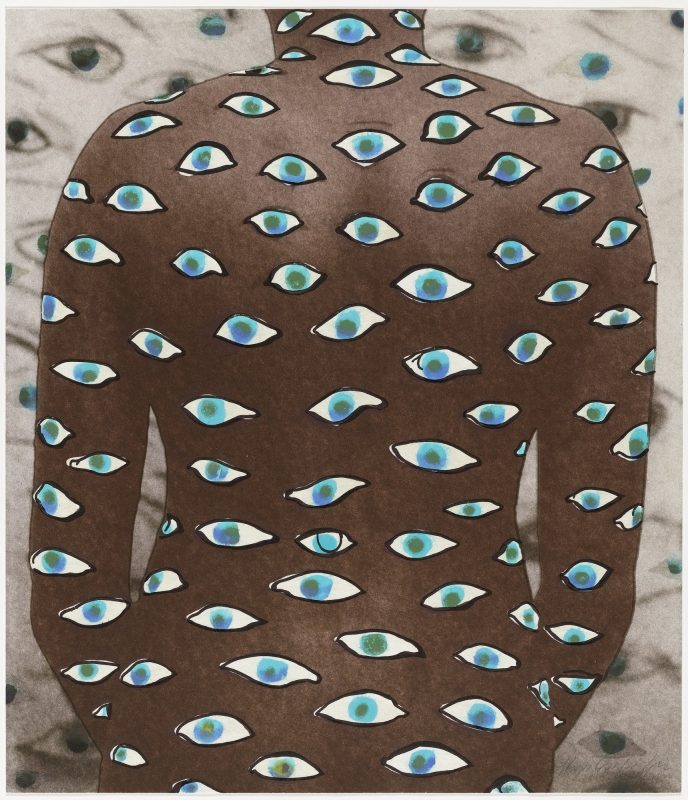

An eye, recreated into image or iconography, has been iterated throughout time as a symbol of ubiquity. Behind the eye rests the methods with which society has believed itself into actualization: sight. In this gazing, there is an innate play with power that remains latent, yet somehow world-affirming. The eye as protection or healer or all-knowing or all-mighty- each iteration suggests a precondition to existence in the public and political sphere that depends on watching, on being seen in order to appear. The eye establishes the stage of life we bear witness to and every being opens wide, retina capturing light rays, processing them into impulses, with millions of small nerve fibers telling the optic nerve to…Start the show.

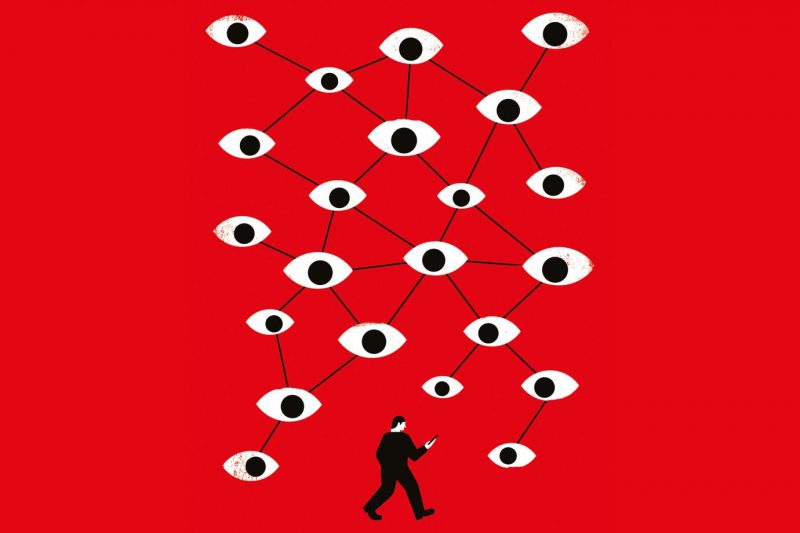

As society grows increasingly dependent on image making in the reproduction of affect and passions that drive politics, our eyes denote not only what we understand, but how we reach such an understanding. As spect-actors in the realm of political publics, our incessant watching, whether through the glow of smartphones, the webs of social media, and whether mediated or not, does not rescue us from any blame concerning the downfalls of modernization. Information continues to circulate and find its intended viewers, or it is kept out of view, redacted, or self-censored. Keeping our eyes wide shut is also a political decision.

We are no passive audience.

We are active participants in a politics driven by perceptions and dependent on our will to knowledge contingent on a collective identity. Our inclination towards an assembly of bodies frames sociability as the thread of reason, an evolutionary marvel developed as a tool to be weary not of one’s own judgements, but the judgements of others. In such a Rancièrian “distribution of the sensible,” certain subjects are left outside of recognition. As Judith Butler would note, framing techniques are never innocent. We have formed a civilization constructed by affirmations, illusions, “expertise”, elongated terms of conditions, dress codes, myths, and dispositifs of power: systems of surveillance, scapegoating, and censorship. Our challenge remains, to envision alternative configurations of the world, to engage in acts of transformation, proposing the possibilities of other worlds, together. In short, to look within to direct our gaze towards new lines of sight.

And so it is as if one must learn to direct their gaze; what one hears must find a fertile path.

-Subcomandante Marcos, “Between Light and Shadow”

Because while someone rests, someone else continues the uphill climb.

In order to see this effort, it is enough to lower one’s gaze and lift one’s heart.

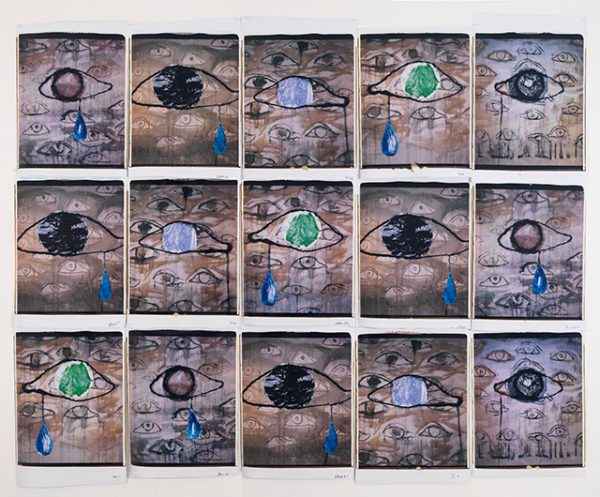

Dragonfly Eyes: The Power of the Gaze

Eyes witness, collect, communicate and convey. It begins with fact but goes beyond that to generate and circulate information, transmit feelings. The gaze of eyes also draws attention, attracts more gazes by generating its own narrative. When this is true to every eye, imagine how such a complex effect would be amplified when there are millions of them?

In the year of 2017, a contemporary art work called Dragonfly Eyes made its debut. It is an eighty-minute indie film created by a New York City based artist Xu, Bing and his team. Dragonfly has 28,000 eyes that altogether blink 40,000 times per second, constantly watching, searching, collecting and examing useful data — a perfect metaphor for the surveillance camera. This is where the film comes from. Xu, Bing’s studio made a straightforward statement saying that “this is a film without actors or camera crews. All the visual material has been taken from public surveillance videos” (Dragonfly Eyes trailer 2017).

A statistic shows that up until the year of 2015, more than 26,000,000 surveillance cameras are working throughout the world, and the number keeps increasing by 15% each year. Xu, Bing’s team had the country’s cameras working 24-7 for them, collecting images of all appearing bodies. A huge amount of surveillance footages are uploaded onto public websites, and that is where Xu, Bing’s studio get access to them. The film creates a fiction that focuses on the tragic marginal life stories. People could take glimpses of all kinds of precarity, including poverty, betrayal, body shaming and cyberspace violence. Two main female characters end up vanishing from the sight, leaving no traces ever after. The film is also made through an utterly reversed filmmaking process, as the team first collected the footages of surveillance security cameras all over China, examined closely and categorized them, then developed a script based on what they have seen. Finally the selected recordings were edited into a narrative and also fictional film tinged with absurdity.

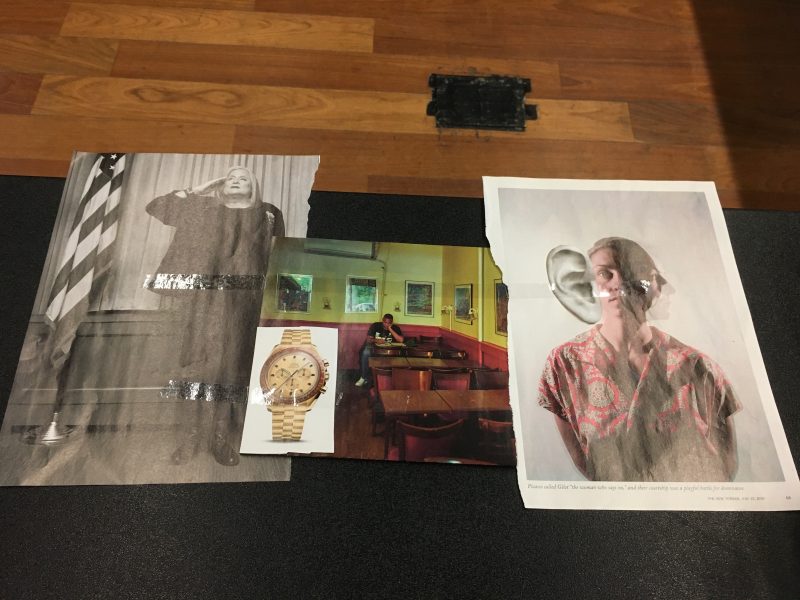

Seeing: The Biopolitical Regulation and Commodification

This is a unique film where its 11,000 hours of footage come from “live records” of daily human performance captured by CCTV. The fact that “actors” and “spectators” can be created with surveillance footage is quite alarming. We as commoners are putting on real life shows every day in front of surveillance, exposing ourselves to forceful eyes. It resembles a new era of sovereignty which Foucault would characterize as biopolitics. Instead of executing power through fatal punishment, regulation is now achieved through maintaining bodies as the way authority demands and making people live for reproduction. “We…are in a society of ‘sex’, or rather a society ‘with sexuality’, the mechanisms of power are addressed to the body, to life, to what causes it to proliferate, to what reinforces the species, its stamina, its ability to dominate or its capacity for being used” (History of Sexuality 1978, 147). Bodies become the greatest property. People are made to look the same, appear appropriately in a fixed way, behave as required and serve the society well for a greater good. These are the norms, and the necessary conditions of living. Failing to behave accordingly would lead to a new form of precarity where life becomes vulnerable and more accessible to power than ever.

Moreover, as participants of the civil society, once accommodated to its mindset and normalized social structure, people sometimes willingly commodify others’ bodies, and therefore consent to commodifying their own. Bodies and related information are collected as data points in exchange for social security. In many cases, people even rely on surveillance cameras to peek at others, for example, when looking for lost property, or trying to identify someone responsible for accidents or crimes, or perhaps to regulate and rule out the “misfits” by “fragmenting” and “creating caesuras within the biological continuum addressed by biopower” (Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-76, 255), in order to make society healthier and purer. There has always been an undeniable desire to see more, as people think it means knowing more about others, and a better chance to protect oneself or one’s property from harm. However, the hidden trick is that seeing is mutual. At the very same time, we are offering our bodies to be monitored and regulated. We become visible, traceable, touchable, and extremely vulnerable. Without full awareness, we are already gaining power from seeing, but also losing power to it. Just as the ending of the film implies, the only escape would be a “disappearance” from all sight, to give up civil rights and most probably, life itself.

Gazing Back at the Veil

To take a step forward, Xu, Bing made his efforts to reveal the hierarchy framing Dragonfly Eyes. Editing raw materials excerpted from documentary videos into a narrative film is an act that amplifies the power retained in seeing. This footage prying and probing into people’s daily appearance and privacy is not supposed to be seen by the public, especially under censorship. All films in China shall be approved by the Chinese National Radio and Television Administration and given a logo of a dragon on a grass green background prior to public release. Whereas Dragonfly Eyes is not one of them. However, Xu, Bing chose to add the logo to the beginning of the film, in a way as an irony of censorship. He also made sure that all footages he used are of public access, and trie to get in touch with some of the people that actually appeared in his film, discussed about the art creating process and asked for consent of using their images, their presences. Such effort is an acknowledgement of current situation, also a meaningful attempt to inform.

By creating a new narrative and putting it into public accesses such as film festivals and modern art museums, Xu, Bing also creates his own audience to break down such a one-way routine. His work activated the power of seeing the unseen through a peeking hole that he, as a renowned artist, is privileged to make and “legitimize” inside the realm of art. Empowered and affected by the embodied storytelling, the audiences naturally align with him.

The logic of digital media also plays a significant role in this process. The digital era is now the era of replication. What contributes to the value of art is no longer authenticity, but the re-framing it does through copying the same content into different context. The process of taking elements of daily life and reorganizing them into a “field” that people can perceive from a different perspective, or even letting them interact, can make “the transparent codes of hierarchy opaque and impossible to miss. Once these codes are perceived, a critical understanding quickly follows through dialogue” (CA Ensemble 2000, 160). Following such a principle, Xu, Bing deliberately turns every single person into a complex combination of both actor and spectator. Consciously or not, bodies are conducting actions throughout life. People live as live performances. On the flip side, people also live as audiences all the time. Although sometimes blinded by the deliberately constructed veil of sovereignty, the capability of seeing is always there, accompanied by the potentiality of doing. As Diana Taylor inferred, “the debates about what can and cannot be known through vision, and how spectators evaluate what they experience, continue into the present and are now further complicated by the prevalence of mediated spectacles and interactive digital technologies” (Taylor 2016, 75). Bodies are manipulated into spectacles that appeal to the public’s eyes and minds, and because of its kinship with feelings and emotions, opinions opposed to the truth can be projected and inserted all the way through, making the identification dangerously political. Then the newly born spect-actors—which is generally everyone under surveillance—would have the opportunity (or capability) to further deliberate, report, discuss and comment, or even interpret the fact as they wish, as in a spiral circle.

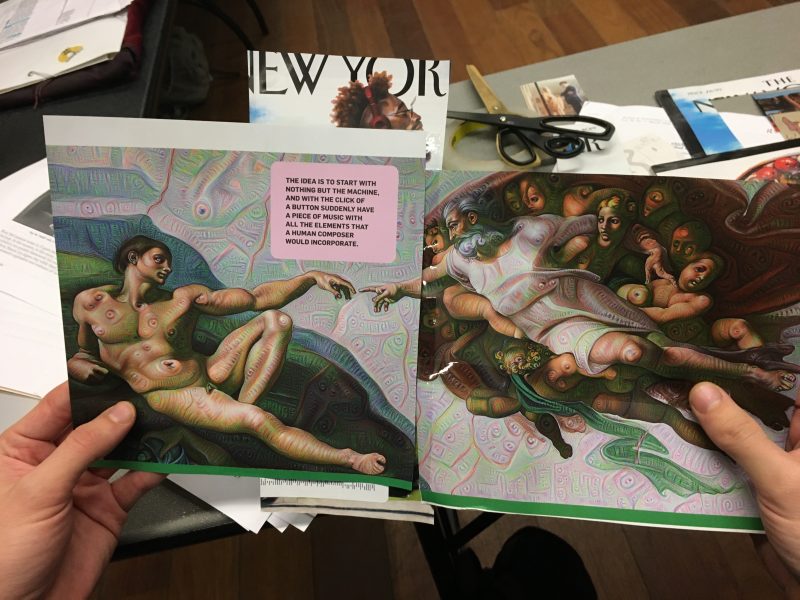

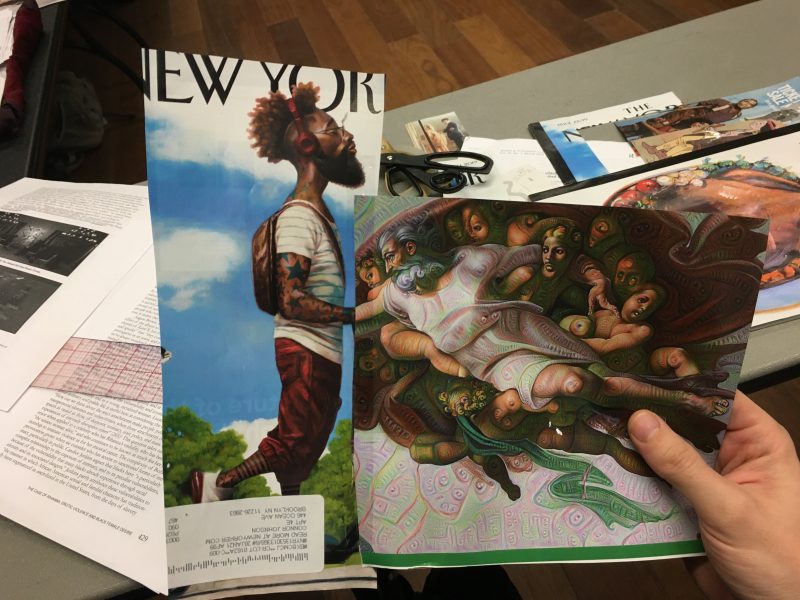

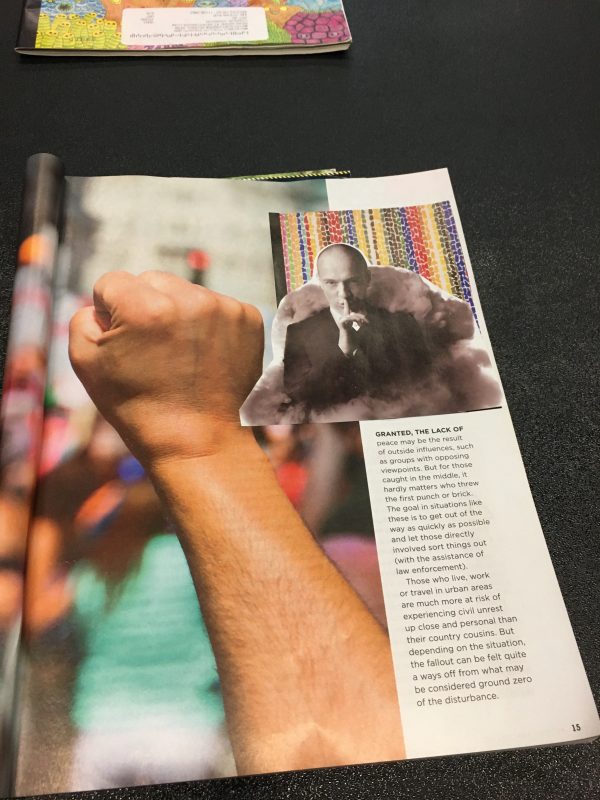

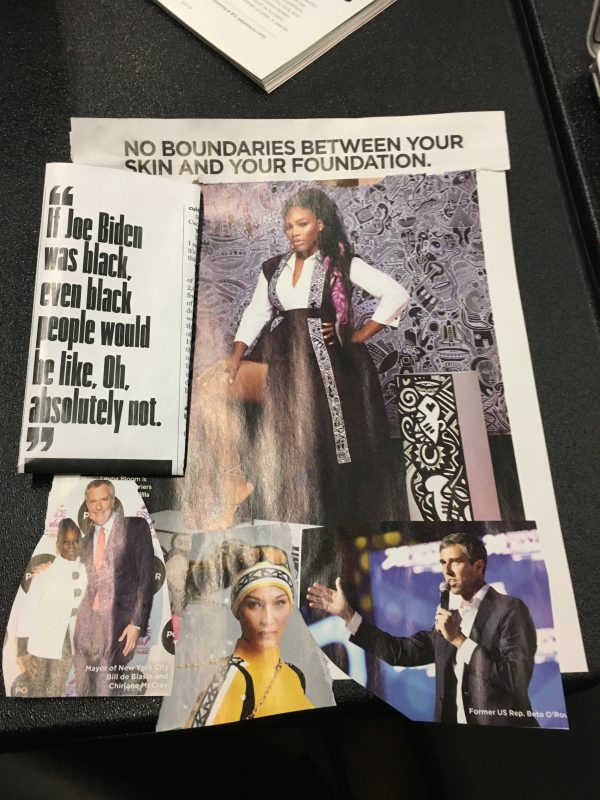

An Exercise in Image (Re)Making

We are constantly confronted with readily-made images awaiting our consumption. What are the possibilities of recontextualizing or reconstructing these images in acts of transformation? These are some of the answers from our class audience.

The Technology of Scapegoating, An Owner’s Manual

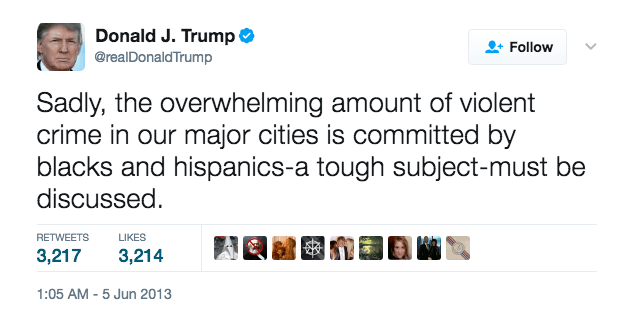

As Renée Girard points out, “the experience of great social crisis is scarcely affected by the diversity of their true causes” . On the contrary, what we see more and more commonly in contemporary politics is how leaders blame minorities for economic crisis, and assemble crowds by weaponizing hatred against those social groups. The “shareable hate”, that is shared via digital media, says Gabriel Giorgi, becomes the raison d’etre of a community that finds in scapegoating a political common affect. The viralization of this hate that leaders promote, then, produces a certain subjectivity, or, as Eric Alliez and Maurizio Lazzarato state, a “war on subjectivity”, that unites a group against a class, a sexual and racial target: a scapegoat, namely, that concentrates the reveries of immunitarian extermination. As digital media facilitate anonymity and the lack of authorial responsibility, to share, to like, to post and to retweet become speech acts that baroquize and carnavalize this hate instigated and enabled by leaders.

How are scapegoats produced and why is their production so effective? Scapegoating, we can say, is a political technology, a set of actions and expressions that follow a protocol, sharply designed by political consultants and marketing advertisers, and that we can trace and reconstruct in an owner’s manual guided by certain patterns of political performance.

Table of contents

Getting started 1) Be as racist and sexist as you can

The resurgence of scapegoating occurs at the same time that fascist leaders return to Western politics and societies. Mauricio Lazzarato, in his latest book, Le capital déteste tout le monde, asserts that this massive hate against minorities cannot be understood without taking into account that racism and sexism and the hierarchies that they produce are the foundational basis of neoliberal economies. Thus, the overwhelming success of leaders such as Bolsonaro, Trump or Macri doesn’t respond to a crisis of Western democracies, but to an intensification of the virulent logics of neoliberal economy. By instigating hate, racism, and sexism these leaders boost the virulent nature of neoliberalism, that needs to discard populations in order to perpetuate the flux and reproduction of capital.

Jeanine Añez Chavez, de facto president of Bolivia after the military coup d’état against Evo Morales, stating: “I dream of a Bolivia free of indigenous satanic rites, the city is not for indigenes, they should go to the forest”. On the other hand, Bolsonaro’s son shared a meme where he mocks the son of the recently elected Argentine President, that practices cosplay, as opposed to his “macho” image with a gun.

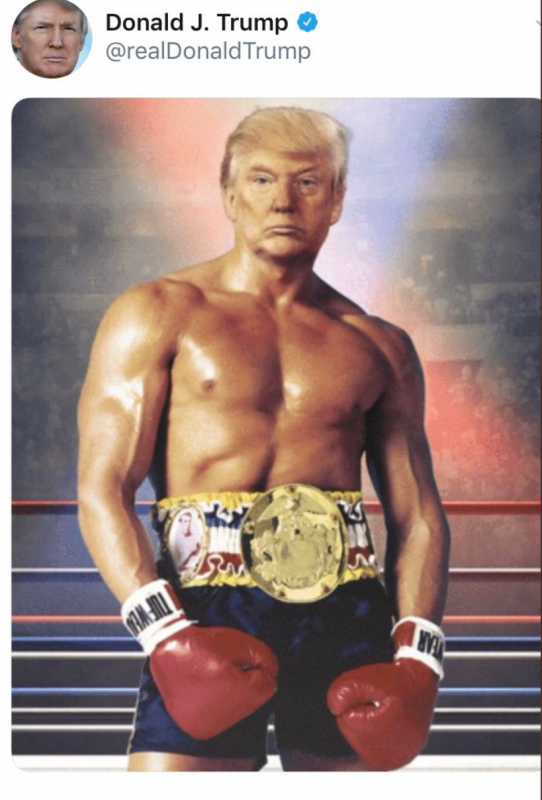

Basic Mode Setup 2) Edify a “folk hero status” using social media

The only novelty that these leaders have (in comparison to earlier fascism) is how they entangle and strengthen their message by the use of social media. The “folk hero status” that they achieve creating an online presence, reaching their base directly, allows them to produce a rhetoric and a performance of hate over the “true facts”. In that sense, the figure of the “netizens”, what Mark Poster defines as “that shares allegiance to the nation with allegiance to the net”, becomes the new digital crowd that supports these leaders and reproduce scapegoating.

Macri, Bolsonaro and Trump are well-known for reaching their base directly and edifying a “folk hero status” via Twitter. Macri during his presidential campaign imitated the celebration of the soccer player Juan Román Riquelme, a star of Boca Juniors, the sports club where he was chairman. On the other hand, Jair Bolsonaro popularized as his mark mimicking a gun with his hands.

Expert Mode 3) Fake news, fake the enemy, fake the social threat

In 2017, the Argentine National Gendarmerie “disappeared” a Mapuche activist, Santiago Maldonado, using the same technique of the last Argentine dictatorship, consisting in illegally detaining, torturing and killing people. In order to justify this crime and the repression against Mapuche communities (its purpose being the land seizure of their territories for oil and mining businesses), the Intelligence Services of Argentina invented an apocryphal terrorist group called Resistencia Ancestral Mapuche that supposedly sought to secede territories of Argentina and Chile to create a Mapuche nation. The idea that this group was a foreign and violent mob that killed innocent people and burned cars and houses was spectacularized by TV shows and instigated hate against indigenous communities.

At the same time, Argentina was suffering a big economic crisis, that was covered by this news.

An apocryphal investigation of the most popular pro Macri journalism television program, “Periodismo para todos”.

Mauricio Macri’s Minister of Security, Patricia Bullrich, answering on Facebook to a follower that supported repression against Mapuche communities and stated that the disappearance of Santiago Maldonado didn’t have to be investigated.

Similarly, Trump targeted Mexican immigrants as rapists and violent people that should be expelled from the US.

Basic Troubleshooting Technique 4) Virality (Build the idea that this group is a viral agent that menaces the social body/ viralize this virus thanks to bots and trolls)

As Roberto Esposito points out, Western politics operates through the logic that the community is a body that must be immunized from the contagion of an external threat. In the case of Trump, throughout his 2016 presidential campaign he called for the construction of a border wall, claiming that if elected, he would build the wall and make Mexico pay for it. The idea that the US must be immunized from Latino immigrants in order to defend itself from moral corruption, unemployment and crime is a pillar of Trump’s rhetoric. On the other hand, to support this transfiguration between the scapegoat and a viral threat, he has stated that Haitian immigrants imported viral diseases such as AIDS to the United States.

Tweet of Mauricio Macri about the apocryphal terrorist group “Resistencia Ancestral Mapuche”, calling them “veneno social” (social poison).

An online comment on the website of the newspaper La Nación about a protest of Mapuche communities, later scanned in verses and transformed into a poem by Roberto Jacoby and Syd Krochmalny.

Bots retweeting a fake news about Santiago Maldonado, stating that he “disappeared” intentionally to destabilize Mauricio Macri’s government, as he was allegedly a family member of Mauricio Macri’s opponent, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

A fake Twitter user sharing a hashtag in favor of Mauricio Macri.

Weaponizing Theatre

PSA by José Alba.

Pete and The Censored Play

By José Alba

The Gift

“I am not coming alone

I am coming with my ancestors

I am coming to embody this institution with the Black body”

“It was a long journey but we came here

With our sister Yemayá”

“Mother take all of me

It took so long

Show your power

Show that we are here to stay” -María Magdalena Campos-Pons, “Habla la madre”

These words are taken from María Magdalena Campos-Pons’ performance, “Habla la madre” (The Mother Speaks), which took place at the Guggenheim on April 27, 2014. On that day, Campos-Pons led a procession of eight female attendants and an Afro-Cuban band through the front doors of the museum to engage in Santería ritual that moved from the lobby to the second floor galleries, creating, through the practice of celebration, new forms of involvement with the museum audience. Campos-Pons’ performance was contextually grounded as part of a weekend of programming around the exhibition Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video. As a commentary on Weems’ achievement as the first African American to have a retrospective in the museum, “Habla la madre” also engaged in a critique “of the raced (white) and gendered (the male) space of the Guggenheim” (Townsend 2016, 2).

While we could say that “Habla la madre” took place at the Guggenheim, it would be more apt to say the performance space of the Guggenheim, for as Campos-Pons’ articulations ring clear, what was at stake on April 27 was a material transformation of the institutional space itself. This transformation, while articulated discursively through the performers’ chants and incantations, was materialized through a reorganization of the institutional space, and the bonds of the performer and spectators within it.

Campos-Pons’ work is intimately personal and relational. Having grown up on a sugar plantation in Cuba, she draws upon her Cuban, Nigerian, and Chinese ancestry in her diverse artistic practice which spans photography, performance, and painting, to only name a few. Campos-Pons’ work is inspired by her multicultural background (her Nigerian ancestors were brought to Cuba as slaves in the 19th century, the Chinese side of her family worked as indentured servants in sugar mills) that is cut by intersecting histories of displacement, survival, defiance, and celebration (Zaya 2016), narratives that she seeks to preserve in her works which engage in the labor of collective memory.

When I first started doing public performances in the 1990s, I wanted to express something I couldn’t express in my paintings and sculpture. I wanted to put my body in a particular space in a particular moment.

-Campos-Pons

As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o suggests, the performance space is not bound within specific spatial demarcations, rather, it is “constituted by the totality of its external relations to…other centers and fields,” never empty, and always “the site of physical, social, and psychic forces in society” (Thiong’o 1997, 13). This space can be thought of both as relational to other spaces, and a site of their convergence. In her work, Campos-Pons activates, through performance, the connections that converge at a specific space in a specific time. In decrying the marginalization of the black female artist in the institutional space, Campos-Pons engages in political work that confronts the “always striated and hegemonically structured” public space (Mouffe 2013, 91), at the same time as she reorders it into an altar, a place for worship and remembrance. In making her claim by appearing in the space, performing in an act of political spectacle a “bodily demand” (Butler 2015, 11), Campos-Pons also makes clear that she is not coming alone. Through ritual acts, she conjures her ancestors to help her embody the institution as Yemayá, the mother of all living things and the owner of the oceans and seas.

In Campos-Pons’ intervention, the concept of “transformation” has multivalent consequences. Performance, as Diana Taylor asserts, “allows us to see” that change is possible (Taylor 2015, 6, 21). There is a transformation of the performer’s body, first as Guggenheim, donning a white hooped dress mimicking the famous building design, and then as Yemayá, who embodies the space, challenging existing “modes of visibility” or a “distribution of the sensible” in Rancièrian terms that leave certain subjects (in this case black and female) outside of the frames of recognition. There is a change effected on the relationship between the performer and the spectator, who, by becoming involved in the Santería ritual, becomes a spect-actor. Campos-Pons’ bringing of Santería into the Guggenheim not only serves as a way to establish contact with the ancestors, but also gestures to the importance of gathering, together, in her work. Prior to engaging with the audience directly, Campos-Pons performs a communal call and response with her witnesses that is based upon democratic participation (Townsend 2016, 41). While the practices of Santería may not be legible to an unfamiliar audience, it is worth nothing that the religion has developed a complex vocabulary to identify people with different levels of involvements with the rituals and spirits, from aleyo (stranger) to oloricha (one belonging to oricha) (Townsend 2016, 43). Audience participation in “Habla la madre” does not manifest into a desire to make Santería legible or accessible, but rather to take a part in the festive nature of the ritual.

This spect-actorship is actively encouraged by Campos-Pons, who further invites the audience to participate through the gesture of the gift. As she reaches the second floor, Campos-Pons waves the bouquet that she entered the institution with in her hand, chanting, “Yemayá, take care of your children,” and then offers individual roses to various women in the audience. The women receive the flowers, almost intuitively as no words are exchanged in the act. By placing into their hands one of the offerings the artist had brought for Yemayá, Campos-Pons both horizontalizes participation in the ritual and the responsibility to undertake its labor.

“I propose myself as a taking, I am to give away myself”

“I come to you with the energy of my ancestor. With my history, with the gift of the past to the present to the future.” -María Magdalena Campos-Pons, “Regalos”

The performative act of gift-giving takes center stage in Campos-Pons’ performance, “Regalos” (2007). In this intervention, which premiered at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Campos-Pons’ covered her body with small pouches containing drawings and messages handmade by the artist herself. By “wearing” her gifts, proposing herself “as a taking,” Campos-Pons transmits “her history” as a “gift of the past” to audience members in the present. Significantly, the act of “taking” in the performance becomes a form of transmission: rather than one-way actions, gift-giving and gift-receiving becomes an exchange. To follow Marcel Mauss, “exchanges and contracts take place in the form of presents; in theory these are voluntary, in reality they are given and reciprocated obligatorily” (Mauss 2010, 3). By establishing this contract with her spect-actors, Campos-Pons activates an ethical obligation for all: she calls for a reciprocity, for a doing of the labor of memory as a collective act. When she exits the performance space with the words, “Now, I invite you to open your gift and share with everyone,” she leaves the future of the performance to the spect-actors.

I call Campos-Pons’ body transformative not only because of how it is spectacularized in her performances, or what it represents in the museum, a gendered body bearing the legacies of colonialism, but because of what it does in the performance space, which is to use acts of doing “to re-establish a connection—not merely in order to seek a different intellectual commitment, but in order to…encounter a new way of imagining the world” (Zaya 2016). Perhaps this connection is related to Achille Mbembe’s argument for the “collective resurgence of humanity,” one that is “a thinking in circulation, a thinking of crossings, a world-thinking” (Mbembe 2017, 179). Wilson Harris has also argued that the dislocations of the Middle Passage “possessed the stamp of the spider metamorphosis, in the refugee flying from Europe or in the indentured East Indian and Chinese from Asia” (Harris 1999, 152), noting the existence of a “shared phantom limb” in the reconstitution of the dismembered (wo)man. Campos-Pons’ performances center themselves around this crucial aspect of collective doing in acts of re-assembly. At the same time, by bringing together intersecting experiences from her personal history, her interventions open up Harris’ “third space” in imagining the passage to the New World. If performance, ontologically, is “a conceptual ‘territory’ with fluctuating weather and borders” (Taylor 2015, 3), Campos-Pons’ work allows us to approach performance as territory in one sense, as process, but also in a spatial sense: the open borders in her performances are inscribed on her spectacularized body, or her movement between these territories is performed as she physically weaves between the Guggenheim, the spiritual realm, and the memory of the African diaspora, connecting these spaces and creating new entanglements between performer and audience alike.

Fenty-ish: On a Creation of Fandoms

Who invented parties? Who can ever tell where they begin or end? Who insisted they fell from the heavens? Who staged such liberation? And for whom do they promise emancipation? Who waits in mourning to attend? Where do you go when the party’s over? Do you come back to life or go back to death? Are parties a departure from the present or trip to a place we’ve never been?

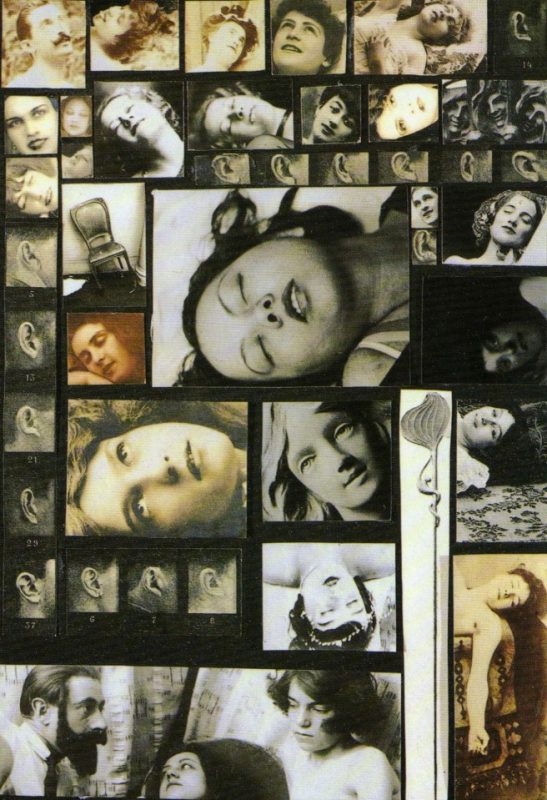

In Salvador Dalí’s 1933 photo-montage, “The Phenomenon of Ecstasy,” the Surrealist artist portrays a collage of images depicting women in the throes of passion, while under various forms of examination and surveillance. Through this spiraling image of intimacy in circulation, Dalí explores the Surrealist interest in the unconscious, dreams, and fantasies, while in conversation with the corporeal phenomena of perception. Many of the images used within this collage were taken by Jean-Martin Charcot, a famous neurologist in the 1800s who often staged his diagnostic sessions into spectacle for the public consumption of the male gaze. Surrealism attaches itself to this gendered perception of hysteria while attempting to emancipate our senses, offering an “alternative exploitation to that of bourgeois society” (Belton 1995) . On the piece, Dalí comments, “Continuous erotic ecstasy leads to contractions and attitudes without precedent in the history of statuary…the repugnant can be transformed into the beautiful through such ecstasy” (Belton 1995). Thus, as art aims to imitate the theatrics of life, Dalí invites our gaze towards a transformation of perceptions, dependent on relentlessness and perversity, always on the brink of fulfillment, but never fulfilled, an image undressed, deemed intolerable, and yet bathed in the desire to appear. The repetition of the female hysteric, a figure noted not only for her sexual abandon but also her intolerable misrepresentation, hints at a politics of passion, described by Diana Taylor as a “mobilization of affect for political ends on collective, structural, and trans-ideological levels” that creeps into discourses of public health (2013). “The Phenomenon of Ecstasy” becomes less about an actual orgasm and more about our perception of its undulating affect.

In his “Theory of the Leisure Class,” Thorstein Veblen insists that it is the political rulers of society, like the businessman who controls means of producing human capital, inevitably affecting social capital, who have fastened themselves as economically unproductive, and thus keen on matters of leisure, and in turn, surveillance. By relinquishing their responsibility to labor required in maintaining a functioning society, these rulers employ an obedient, indoctrinated, and oftentimes desperate working class who carry the bulk of the societal work on their backs. This gives the ruling class more opportunities to exhibit a sentiment of power, through surveillance, conspicuous consumption and leisure, as well as the creation of an exclusive political domain that functions to keep the working class in place. It comes as no surprise then, that this ruling class should use their conspicuous amount of space, time, and human capital to pursue their individual happiness, basking in the spoils of lineage, royalty, nepotism, fame, colonialism, and an abdication to Doom gawked at by the working class, weaponized in the theatrics of Terror and Fear.

Thus ensues a political spectacle of power dependent on a sphere of appearances, where the visibility of resounding information is as important, if not moreso, than the truth of an image, and in turn, the advantage of the framing of normalcy lies in the hands of rulers. Consequently, the individual within the working class is prone to an immobility that hinders any plea to the righteous sovereignty experienced by the few:

The abjectly poor, and all those persons whose energies are entirely absorbed by the struggle for daily sustenance, are conservative because they cannot afford the effort of taking thought for the day after tomorrow; just as the highly prosperous are conservative because they have small occasion to be discontented with the situation as it stands today.

(Veblen 1899, 56)

Elsewhere, within the “Society of the Spectacle,” Guy Debord further exposes this inversion of life handed down unto us, one in which the reality of the Spectacle, what Debord defines as the “autocratic reign of the market economy,” is truly another abdication to Doom, a falsity that assures that continuous and unjust struggle is a necessary evil for those under subjugation (1967). This is Capitalism’s preferred method of distracting and stupefying the masses; by numbing an appeal to liberation. Thus, as Veblen describes in the above, the essential task instilled within the many of the working class is to continuously produce a supportive infrastructure for the few within the wealthy apparatus to expand while maintaining power.

Veblen and Debord tell of a class binary that depends on one population to exist on a lower plane of life than the other. In the face of such corruptive odds, the individual turns to the group for a feeling of solidarity, transforming their flesh into the action of the many, dreaming of a body imbued by a collective consciousness big enough to take on the class in Power. The assembly of an audience, as in the coming together of like-minded spect-actors or participants, is a political move that endeavors to fill the void of power stolen from the working class. When agreement surges with dopamine and people with shared rationale form public spheres of influence, we may witness the establishment of fandoms. Facilitated by the interconnectedness of the Internet and Social Media, fandoms expose the insurgent tendencies of a group hailed into the political domain under the helm of inclusivity and the potency of plurality. Creating a fandom is often dependent on a political actor in which the individual spectactors share a perceived commonwealth of consciousness.

Fashion, like Politics, exists in the realm of performative tradition, both concepts having evolved very cleanly into exclusionary theatre, mirroring the agora, where some individuals are elevated to levels of authority, expecting applause from their catwalk or pulpit, anticipating change in stride with their presentation.

So when Chanel shows at Paris Fashion Week, eyes savor over every garment, every model, gazing backwards and forwards, cognizant of the brand’s historical significance (and prolificness) as well as the communal understanding that Chanel is a brand to watch, an artistic statement that, once developed and packaged as performatic appraisal of lines and limbs, becomes a commodity used to dictate trends, passions, social standing, clout, citizenship, and agency.

Such performatic theatre is an artistic form of coercion that resembles racketeering done by political actors in our modern age, who, now with grand fabulations, pomp, and cunning, must ornament themselves as members of a shared consciousness indebted to a brand, an affective, circular restraint and surveillance deemed credible by how many eyes are watching; how many “likes” or “retweets”; the roar of applause; camaraderie; citizenship; “friends.”

The fandom functions quite similarly in Politics as it does in Fashion; insurgent collectives are thrusted upon public spheres, demanding appearance in plurality. However, both waver with temporality, insisting to remain inflexible within space and time. The fleeting nature of the spectacle encourages a collective fandom always waiting in the wings, prone to rise whenever hailed to defend, salute, or parade around a Fashioned Subject. The commodified rhetoric of Fashion implores the embodiment of the propagated style in order to truly appeal to citizenship just as much as one’s Political Identity can beg you to live your life under a distinct value system.

Fashion Week has an interesting history with political spectacle as some shows send garments down the runway conscious of their cultural critique, while other shows are infiltrated by spect-actors in protest. Just this season, model Ayesha Tan Jones staged a protest against Gucci’s straight-jacket inspired collection as they walked down the catwalk, hands held eye-level, with “mental health is not fashion” scrawled on their outward-facing palms in pen. The same London Fashion Week was commemorated by a staged die-in by climate campaign group Extinction Rebellion outside its venue, thrashing about in buckets of fake blood to symbolize the fashion industry’s role in the deterioration of life on Earth as well as its negligent accountability towards a more sustainable model. And elsewhere, during Paris Fashion Week, comedian and performance artist Marie S’Infiltre crashed Chanel’s latest show in her grandmother’s vintage Chanel outfit, as a means to not only enliven the infamously serious affair, but also to partake in a spectacle that promises glory, basking in the eternity of the Chanel brand.

These examples act as critiques of an industry whose preservation depends on the constant reiteration and belief in itself. All of the mentioned spect-actors take on the role of party crasher, breaching an assembly by satirizing the imaginary borders installed around the spectacle. However, in looking at Rihanna’s Savage x Fenty Show, we see a spectacle that does not seek to exclude, but invites us to crash the esteemed party of Fashion Week.

If fashion shows hope to inspire possibilities in spect-actors, then one that strives for inclusivity should facilitate an entrance point of empathy. Rather than encouraging a prohibited breach of spectacle, it encourages self-actualization through socialization; like equity in action, spilling off the catwalk and into the capacities of the individual. This culminates into a fandom driven by love and an acceptance of different body types.

On the flip-side, Trump and his MAGA cohort have created a fandom dedicated to hate and the reversal of development. It is a fandom that operates under the pretense that “America”, the concept, was once great, encouraging its followers to assemble to envision a future-tense America that is great again. Trump’s consistent rallies contain all the insurgency of a fashion show without the novelty of a new collection or season. He is selling them the same idea in a different space and time. It is an assurance strategy that seeks to communicate to his fandom, who may be watching from afar, that they are a part of something. Thus, fandoms operate under the guise of inclusivity and representation, and are predicated upon participation. Its fashioned subject, its creator, always has an idealized audience member in mind when communicating. Thus, a political actor depends on a circulation of affect to proliferate their vision.

Brian Edwards depicts the genesis of these modern fandoms in his exploration of digital insurgency with “Trump from Reality TV to Twitter, or the Selfie-Determination of Nations.” Edwards defines the selfie as a “globally ubiquitous form of representation” that makes the selfie “a new phatic agent in the energy flows between bodily movements, sociable interactions, and media technologies that have become fundamental to our everyday, routine experience of digital activities” (Edwards 2018, 29).

Edwards goes on to define the selfie-determination of nations as a digitally mediated and performatic community in which the individual, bots, and trolls coexist, learning to make believe and make belief; “It is at times difficult to know who is real and who is a digital creation. Trolls, for example, can be real citizens or they can be bots programmed to respond negatively to political posts. As more and more citizens consume their news and entertainment through handheld devices, via the filters of social media and other servers, two major shifts collide: the blurring of the boundary between news and entertainment…” (Edwards 2018, 40). Here, inclusivity, the hallmark of assembly, mutates to involve the unnatural, the reproductions of intolerability that fabulate a horrific myth of ruling class, subjugating a working class so prone towards fatalism that the negation of the self is welcomed, if only to continue the maintenance of the ritual empathy of the fandom. Trump plays the role of “short circuit” in our network of digitized communication, occupying the space where the “potential for liberation and domination cross” (Edwards 2018, 41) . To map such an audience requires the logics of an Internet culture dependent on the passionate play of world-making.

Such performances are innately political for they depict the potential for radical transformation. Boal contends that if art is to be sovereign, then it should deal with all humans, their actions (or inactions), as well as what is done to them (2008) . Performance spectacle accomplishes this through a catharsis depicting an aside or correction towards humanity; in a purposeful alteration, a new way of orienting the body is enacted and there is potential for the viewer to find emancipation.

The spectacle of Fashion Week is a coercive strategy, placing commodities on display in an artistic and performatic sequence. This is essential if we are to agree with Brecht that theatre in the scientific age should strive for the joys of liberation; liberation from the confines of history; liberation from present conformities of daily life; liberation from precarious potentials of the future. Judging performance through issues of true/false or those of being/pretend becomes futile; what gives these mediated acts their effectiveness is in their affectations, or even more precisely, the inspiring potential in the emotional weight of their movements.

That being said, Brecht would not want us to ignore the contradictions of our given world when tempting this intersection. This season’s Savage x Fenty is seemingly cognizant of Brecht’s appeal, so, unlike the initial acts of protest described here, this political spectacle strives to deconstruct the fashion show format rather than puncture its beloved iterations. In this way, it establishes a new world of expression that is not totally dismissive of the power structures it critiques, but instead works within its bounds of artifice, simultaneously challenging its norms and expectations.

The show introduces new performatic possibilities for a fashion show by highlighting the brand’s inclusive ambitions and blowing them up in a colorful display of lingerie, sleepwear, dance, and song. Interestingly, the audacity of this political spectacle makes each choreographed song or dance number seem more like performance of protest, seamlessly oriented around a multiplicity of body types and gender identities marching before a fashion world that does not typically champion their body or existence. Savage x Fenty reasons with the idea of fashion as a protection from human nature’s more restrictive tendencies in an attempt to promote modern nature (and all its inconsistencies) at its most cathartic.

If we consider Arendt, political action can only take place on the condition that the human body makes an appearance (1958). In being witnessed, various perspectives concerning the body depend on such displacement in order to establish coherence. Butler contends that this is how political action persists- the space in between actors. The emancipation we feel does not emit from the individual, but the relation among individuals. Thus, political revolution by way of spectacle cannot be commenced by a single instance, but by the radical solidarity of the “us.” Both Arendt and Butler concur that human dignity is championed by social relations that strive towards acceptance in the name of equality.

Butler adds that, “The claim of equality…is made precisely when bodies appear together, or, rather, when, through their action, they bring the space of appearance into being. This space is a feature and effect of action, and it works, according to Arendt, only when relations of equality are maintained” (Butler 2015, 88-89). The life that emits from a body, although it may not be as readily apparent as a garment, must still seek out means of perseverance, especially when it is at odds with a domineering hegemony. Such queered conditions of perseverance inevitably depend on sociality, and in turn, ask for the radical reorganization of established mores in order to carve out a space to thrive. In light of this, I propose: If fashion has become a means of simultaneous protection and expression, notably for minoritarian subjects who are disenfranchised by the industry’s historicized limitations, then it is in turn a political sphere where we should not only make room for such bodies to exist, but also make this a paramount objective, in the name of equality for all.

By opening up the fashion discourse to include traditionally excluded bodies in a realm that champions political post-structuralism, Rihanna’s Savage x Fenty Show aims to provide a typically forgotten or disposable population within the confines of fashion the right to be seen, to take action, in a display of fashion insurgency, with Rihanna, a pop star who has turned her Mass Appeal into Mass Affect, conceding to the role of conductor, facilitating an assembly or fandom that is not all about her, but in fact, all about us. In this way, the brand diverges from a fandom driven by hatred and the need to divide humanity by constructing a working class. Instead, a traditional concept of leisure and exclusion is challenged, affording not only lingerie styled by an international pop-star, but also, the affect that surrounds lingerie; that of obtainable freedom and self-presentation.

Both Trump and Rihanna are examples of party crashers within politicized realms. They represent the ongoing blurring of entertainment and politics, sharing similar digital domains, and challenging established conventions, all while rehearsing for a future or an After Party in real time. To crash a party is to breach the perceived barriers of a spectacle, inviting spect-actors in one world to come into your own. Party crashers are radicals, so emboldened by their own theatrics, that their performance makes an alternative bid for staged emancipation. It is this audacity that ushers in the fandoms who bask in their will to action, constructing an audience out of subjects disenfranchised or excluded from a portrait of leisure, a perception of ecstasy.

Works Cited

Alliez, Eric and Lazzarato, Maurizio. Wars and Capital. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2018.

Belton, Robert James. The Beribboned Bomb: The Image of Woman in Male Surrealist Art. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1995.

Boal, Augusto. Theatre of the Oppressed. New edition. Get Political 6. London: Pluto Press, 2008.

Brecht, Bertolt. A Short Organum for the Theatre. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic, 1st. Ed. New York: Hill and Wang.

Butler, Judith. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Critical Art Ensemble. “Recombinant Theatre and Digital Resistance.” The MIT Press, TDR, 44, no. 4 (2000): 151–66.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

Edwards, Brian T. “Trump from Reality TV to Twitter, or the Selfie-Determination of Nations.” Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory 74, no. 3 (2018): 25–45.

Espósito, Roberto. Immunitas. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011.

Foucault, Michel. “Society Must Be Defended.” In Lectures at the Collège De France, 1975-76, translated by Arnold I. Macey, 239–63. New York: Picador.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. First American Edition. Vol. An Introduction. 1 vols. New York: Random House. Inc, 1978.

Giorgi, Gabriel. “La literatura y el odio. Escrituras públicas y guerras de subjetividad”, Revista Transas (March 2018). http://www.revistatransas.com/2018/03/29/la-literatura-y-el-odio-escrituras-publicas-y-guerras-de-subjetividad/

Girard, Renée. The Scapegoat. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Harris, Wilson. 1999. Selected Essays: The Unfinished Genesis of the Imagination. London and New York: Routledge.

Jacoby, Roberto and Krochmalny, Syd. Diarios del odio. Buenos aires: n direcciones, 2016.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. Le capital déteste tout le monde. Fascisme ou révolution. París: Éditions Amsterdam, 2019.

Mauss, Marcel. 2010. The Gift. London and New York: Routledge.

Mbembe, Achille. 2017. Critique of Black Reason. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Mouffe, Chantal. 2013. Agnostics: Thinking the World Politically. London and New York: Verso.

Poster, Mark. Information Please. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2006.

Taylor, Diana. “Percepticide.” In Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War,” 119–281. Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

Taylor, Diana. Performance. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016.

Townsend, Phillip A. 2016. “(Re)Framing Resistance and (Re)Forging Solidarity: Negotiating the Politics of Space, Race, and Gender in Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons’ ‘Habla La Madre'”. The University of Texas at Austin.

Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class. Dover Thrift Editions. New York: Dover Publications, 1994.

Wa Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ. 1997. “Enactments of Power: The Politics of Performance Space.” TDR: The Drama Review 41, No. 3: 11-30.

Xu, Bing. Dragonfly Eyes, 2017.

Zaya, Octavio. 2016. “Becoming FeFa.” Revista Atlántica 57.